No poet since Shelley sings more loftily or with more fiery passion or with finer thought than Swinburne when he is arraigning priestcraft before the bar of humanity and truth.

The Literary Guide, 1 October 1903

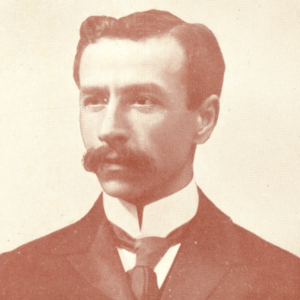

Algernon Charles Swinburne was a writer, critic, and freethinker, recognised as one of the most significant poets of the 19th century. Known for his musical verse and rebellion against traditional Victorian standards of morality, he was much admired by humanists of his day: an outspoken rationalist, who also epitomised the power of creativity, imagination, and art.

Born in London, Swinburne grew up at East Dene, Bonchurch, on the Isle of Wight, and was educated at Eton and Balliol College, Oxford. Though he ultimately left without a degree, Swinburne’s time at Oxford was influential on his developing poetic tastes and voice, and his rejection of Christianity. While there he met the artists (and fellow freethinkers) Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Morris, and was active in the Old Mortality Society, a group devoted to free inquiry and freedom of discussion. On leaving Oxford, Swinburne’s father provided him an allowance of £400 per year, enabling him to pursue writing. He published his first book in 1860.

The years that followed were prolific, with Swinburne writing poems, plays, essays, and a book on William Blake. In 1866, he published Poems and Ballads. With its themes of republicanism, rebellion, sexual freedom, and anti-Christianity, the book caused a storm of controversy (Punch labelled him ‘Mr. Swineborn’), but cemented Swinburne’s reputation as an original, masterful poet. In 1871, he published Songs before Sunrise – similarly political and philosophical.

During his lifetime, Swinburne was a significant inspiration to his fellow freethinkers – both for the beauty of his verse and his unapologetic atheism. In an article published in The Literary Guide (now New Humanist) five years before his death, the writer opined:

Throughout the work of this poet rings out clearly and unmistakeably the challenge of Freethought. A superb dreamer of dreams, Swinburne has given us something more than merely beautiful utterances. He has taught us soldiers of Rationalism that it is good to act during life, and not to lie down and sulk. The call to arms vibrates through his magnificent poetry, as in that of Shelley, and not without result. As we march to battle against the hosts of superstition we are nerved to fresh endeavours by hearing the glorious music of a great poet.

The writer quoted from Swinburne’s ‘Hymn to Prosperpine’:

O ghastly glories of saints, dead limbs of gibbeted Gods!

Though all men abase them before you in spirit, and all knees bend,

I kneel not neither adore you, but standing, look to the end.

Swinburne, ‘Hymn to Proserpine (After the Proclamation in Rome of the Christian Faith)’ in Poems and Ballads (1866)

Swinburne himself made a selection of the poems he felt best represented his attitude towards religion, referenced in a letter written by his friend Theodore Watts-Dunton to Literary Guide founder Charles Albert Watts in 1914. Quoting Watts’ own description of Swinburne’s ‘humanistic enthusiasm’, Watts-Dunton listed ‘Hertha’ and ‘By the North Sea’ as having been among those chosen by the poet.

Prone to ill health and self-destructive behaviour, in his later years, Swinburne’s excesses—especially his alcoholism—led to his being taken in by Theodore Watts-Dunton, who helped him adopt a more subdued lifestyle. Swinburne lived with Watts-Dunton at his home in Putney for the last 30 years of his life, where his literary output remained substantial. Swinburne died in 1909.

True to his beliefs in life, Swinburne had requested that there be no religious service at his burial – in fact, he wanted it to be silent. This was ultimately disregarded and, as stated in The Literary Guide, 1 July 1914: ‘At the interment a priest was allowed to recite the ritual of that religion which had been wont to excite the whole vocabulary of the great poet’s scorn.’

Content thee, howsoe’er, whose days are done;

Swinburne, ‘Ave Atque Vale’ (In memory of Charles Baudelaire) (1868)

There lies not any troublous thing before,

Nor sight nor sound to war against thee more,

For whom all winds are quiet as the sun,

All waters as the shore.

As an outspoken champion of rationalist ideas and ideals, Swinburne was much admired by humanists during his lifetime and after. Decades after his death, humanist E. M. Forster quoted Swinburne in Two Cheers for Democracy (1951), referencing the line from ‘Hertha’ (1871), ‘Even love, the beloved Republic, that feeds upon freedom lives’, in writing:

So Two cheers for Democracy: one because it admits variety and two because it permits criticism. Two cheers are quite enough: there is no occasion to give three. Only Love the Beloved Republic deserves that.

E. M. Forster, ‘What I Believe’ in Two Cheers for Democracy (1951)

Swinburne did much to help shake the stranglehold of conservative custom and challenge the role of the Church, as well as to emphasise the importance of living the one life that is guaranteed. As he wrote in ‘Hymn to Proserpine’:

… for a little we live, and life hath mutable wings.

A little while and we die; shall life not thrive as it may?

For no man under the sky lives twice, outliving his day.

Algernon Charles Swinburne, ‘Hymn to Proserpine (After the Proclamation in Rome of the Christian Faith)’

The Conscience has eclipsed the Scriptures; Science has destroyed the belief in Divine Interposition; Democracy and Civism have shown men […]

No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty […]

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

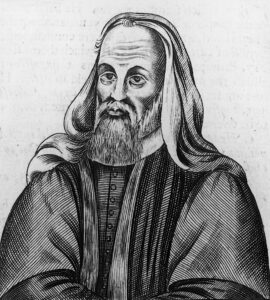

Pelagius lived between the fourth and fifth centuries, and advocated a heretical Christianity that emphasised free will and humanity’s capacity […]