I don’t think it’s the novelist’s job to give answers. He’s only concerned with exposing the human situation… and I hope my books touch the heart now and again.

Angus Wilson, interview with Michael Millgate, in Writers at Work: the Paris Review Interviews (1972)

By Peter Faulkner, originally published in New Humanist, September 1991

The recent death of Angus Wilson has deprived humanism of one of its most committed and deviously eloquent voices. From the publication in 1949 of The Wrong Set to that in 1980 of Setting the World on Fire Wilson brilliantly, and at times savagely, exposed many aspects of English middle-class life, and recorded its competitions and humiliations, and above all its anxieties. Wilson did not start writing until early middle age, so that the short stories which form his first publications draw on several years of acute observation of human behaviour in the world of his experience — a world sometimes raffish, sometimes seedy, sometimes successful, but never solid and reliable. The great source of pleasure for the reader of the short stories continuing in Such Darling Dodos and A Bit Off the Map was Wilson’s wonderful ear for the varieties of English speech. The vision of life behind these stories is far from optimistic: their world is one of relationships turning into fetters, and attempts at freedom into loneliness and sometimes despair. But the authorial presence transforms the bleakness through the intelligence and wit of the presentation, so that the reader is enabled to see what the characters are blind to, and so achieve a sense of possibility denied to them.

The vision of life behind these stories is far from optimistic: their world is one of relationships turning into fetters, and attempts at freedom into loneliness and sometimes despair. But the authorial presence transforms the bleakness through the intelligence and wit of the presentation, so that the reader is enabled to see what the characters are blind to, and so achieve a sense of possibility denied to them.

However, Wilson came to find the short-story form too constricting, and moved to the novel in Hemlock and After in 1952, with its brave and moving portrayal of Bernard Sands trying to come to terms with his homosexuality in a society too frightened to be tolerant. The novels develop expansively in Anglo-Saxon Attitudes (1956) and The Middle Age of Mrs Eliot (1958), with their humane focus on the possibilities of renewed life for those who can accept difficult truths about themselves.

The scope of these novels reminds us of Wilson’s enthusiasm for much nineteenth-century fiction, clear from his study of Zola in 1950 and, more excitingly, of Dickens in 1970: a more idiosyncratic note is struck by his choice of Kipling in 1977. The Old Men at the Zoo (1961) showed Wilson writing in a more succinct and almost allegorical vein, but he returned triumphantly to a mode of psychological realism with Late Call in 1964. Wilson is a male novelist who can write with much sympathy for his women characters, and Sylvia Calvert is a great creation as she struggles to build a new life for her ageing self in the alien environment of a New Town. Few novelists have attempted to render the possibilities of life for such elderly protagonists: Wilson here does so with insight and conviction.

Wilson had the courage to respond to the changing mood of the times by moving away from his earlier method in No Laughing Matter in 1967. This is a family saga remotely deriving from a writer like Galsworthy, but the treatment is a mixture of modes uniquely Wilson’s, combining direct narrative with parody, pastiche and dramatic interludes to convey the story of the six children of the Matthews family, and through them the changing shape of English bourgeois society in this century. As If By Magic (1973) is by contrast a peripatetic novel with moments of farce and tragedy (which come very close together), and ending with an intelligently critical allusion to one of Wilson’s obvious precursors, E. M. Forster. His final novel, Setting the World on Fire, attempted allegory about the England of the 1970s, but lacked the vivid speech characteristic of his best writing.

At a time when we are encouraged to acknowledge the work of Graham Greene, it is to be hoped that we may also think again of Angus Wilson, and return to his books for their bracing combination of a realistic acceptance of humanity in all its confusions with a humanistic belief in the possibilities of life and change.

All in all Wilson’s is a remarkable achievement, but one that is sadly unrecognised at present. At a time when we are encouraged to acknowledge the work of Graham Greene, it is to be hoped that we may also think again of Angus Wilson, and return to his books for their bracing combination of a realistic acceptance of humanity in all its confusions with a humanistic belief in the possibilities of life and change.

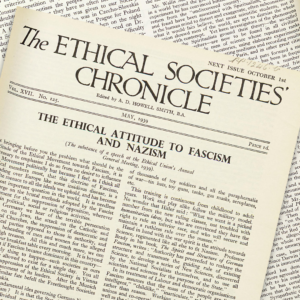

From The Ethical Societies’ Chronicle, Vol. XVII. No. 125. May 1939 The Ethical Attitude to Fascism and Nazism (The substance […]

Sarah Flower Adams was a writer, radical, and major influence on the religious thinking of William Johnson Fox at South […]

While much of the Humanist Heritage website looks back to the earlier years of the organised humanist movement, recent decades […]

Ludovic Kennedy was a writer, journalist, and broadcaster, known for his investigations into miscarriages of justice. A human rights campaigner, he […]