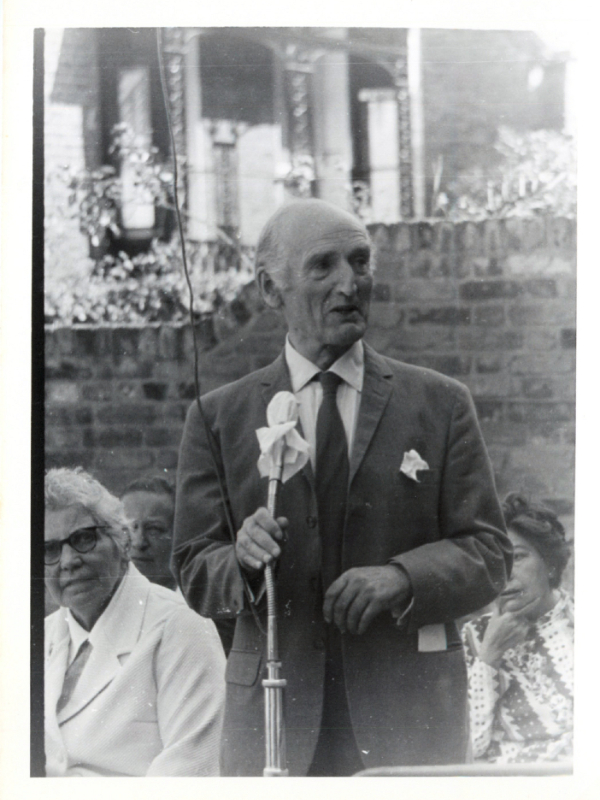

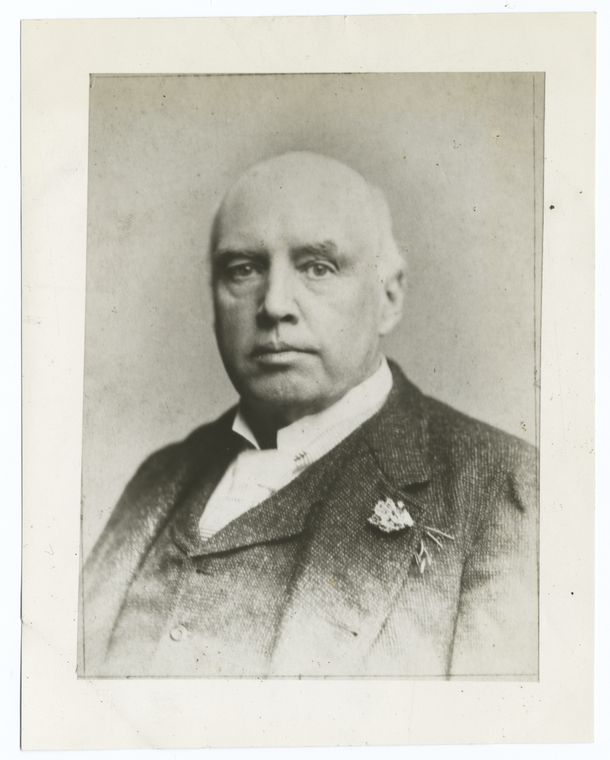

Humanists and freethinkers have been among the longest standing advocates for compassionate reform of the laws related to assisted dying. In the US, Robert G. Ingersoll, ‘the Great Agnostic’, and Felix Adler, founder of the Ethical movement, were two of the earliest public proponents of what was then called ‘suicide’ in the case of the incurably suffering, and in the UK, active efforts to change the laws have been spearheaded by the non-religious. Historically rooted in humanists’ rejection of traditional religious arguments about the god-given sanctity of life, and the ‘heroism’ of enduring affliction, support for the legalisation of assisted dying among humanists focuses instead on individual self-determination, emphasising the minimising of suffering and the exercise of reason and compassion in arriving at moral decisions.