Raising awareness

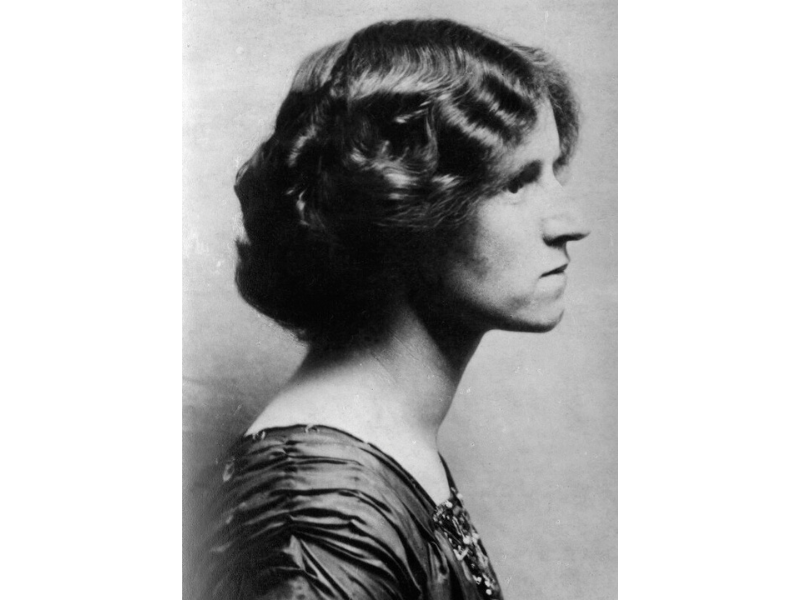

From early efforts to humanise the treatment of the mentally ill, to improving discourse and education around mental health, humanists have played a role. In 1834, Harriet Martineau described the state of most asylums as ‘the most deplorable spectacle which society presents’, urging rational, compassionate care, and efforts to address the stigma and fear around mental illness. More than a century later another humanist, developmental biologist and Vice President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) Lewis Wolpert, published Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression, doing much to bring conversations around mental health into the public sphere. In 2021, Humanists UK and its patrons Eddie Marsan and Janet Ellis partnered with the NHS (itself spearheaded by a humanist) to promote mental wellbeing and reflect on the mental health impacts of lockdown. Marsan reflected: ‘What lockdown – as a humanist – has made me realise, is the importance of people in our lives, how interconnected we are and how we all need each other’.