The right to liberty and freedom

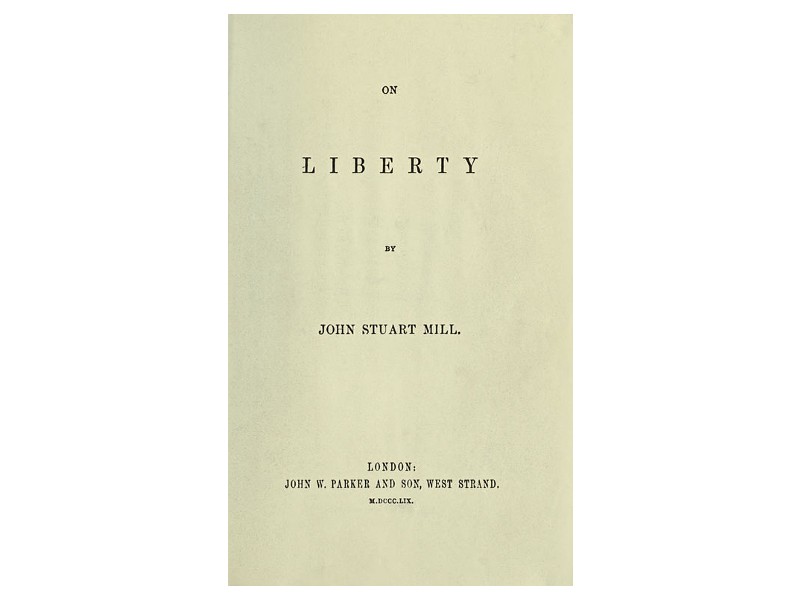

On Liberty (1859)

John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty was a philosophical essay exploring the idea of civil liberty: ‘the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual’. In it, Mill applied the philosophy of utilitarianism (what is right being what produces the greatest good for the greatest number) to the relationship between the individual and the state. It was in On Liberty that Mill expressed a belief central to the humanist approach today, arguing that:

The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way… The liberty of the individual must be thus far limited; he must not make himself a nuisance to other people.