To say that “God moves in mysterious ways” is to put up a smokescreen of mystery behind which fantasy may survive in spite of all the facts.

Barbara Smoker, ‘So You Believe in God!’ (c. 1974)

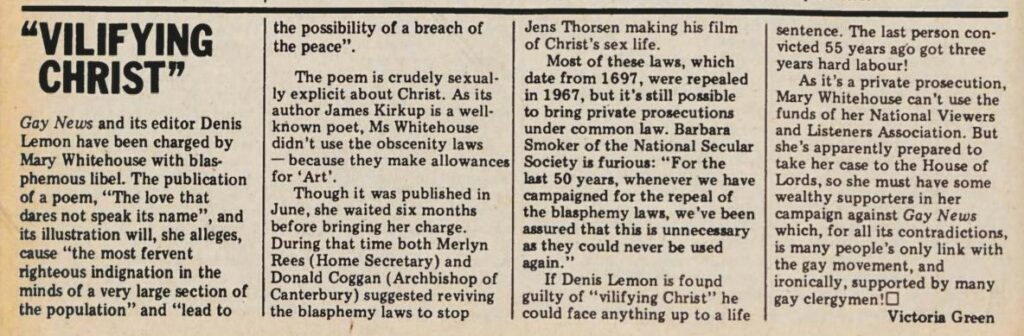

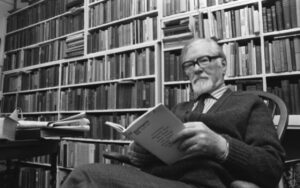

Barbara Smoker was a humanist activist for seven decades, and President of the National Secular Society for a quarter of a century. After renouncing religion in her 20s, Smoker became one of the UK’s most prominent voices for humanism, throwing her boundless energy behind myriad causes. These included campaigns for dignity in dying, peace, and animal rights, and against faith schools, blasphemy laws, and the death penalty. As Andrew Copson said after Smoker’s death in 2020, hers was ‘a long and exuberant life of activism’, for which society at large owes ‘an enormous debt of thanks’.

… we all make our own purposes as we go through life. And life does not lose its value simply because it is not going to last forever.

Barbara Smoker, ‘Why I am an Atheist’ (1985)

Barbara Smoker was born in 1923, and raised in a Roman Catholic family. She was a pious child, and originally intended to become a nun. In hindsight, she wrote, her horror at discovering the deception of Father Christmas aged ten might well have marked both the beginning of her loss of faith, and of her ‘persistent missionary zeal in proclaiming scientific truth’. However, it wasn’t until 1949, at 26, that Smoker would finally renounce religion, ‘with a tremendous flood of relief’.

From then on she embarked on a lifetime of humanist activism, for ‘there was never any possibility of a halfway house between the Catholic Church and atheism’. Drawn first to the writings of Hector Hawton, whose early devoutness and subsequent atheism resonated with her own experiences, Smoker joined South Place Ethical Society, of which Hawton was Secretary. She also admired the eloquent humanism of H.J. Blackham, who she travelled to hear speak at Bayswater’s Ethical Church. She was a member of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) from the 1950s.

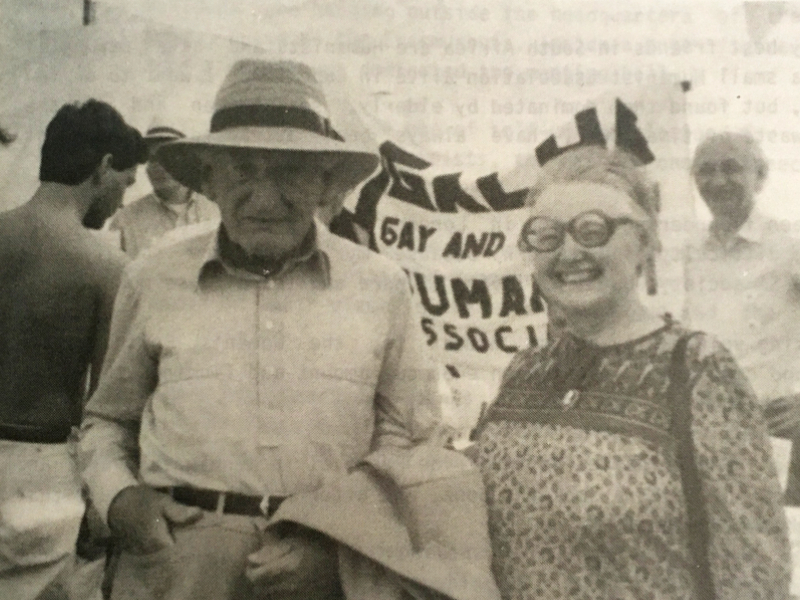

Smoker’s subsequent roles included Secretary of the Shaw Society; Secretary of the Phonetic Alphabet Association; President of the National Secular Society (1972–96); Vice President of the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association (now LGBT Humanists); founder, chair, and later Honorary President of South East London Humanists; President of Bromley Humanists; committee member of the Lewisham Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament; Appointed Lecturer of the Conway Hall Ethical Society; and chair of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society (now Dignity in Dying) from 1981-1985. She later transferred her support from the latter to My Death, My Decision, following a policy change removing support for assisted dying in the case of the incurably suffering. Smoker compiled and edited Voluntary Euthanasia: Experts Debate the Right to Die (1986).

She was also the author of influential pamphlets on the humanist outlook for both the British Humanist Association (What’s This Humanism?) and the National Secular Society (So You Believe in God!). Humanism, a book aimed at young people, was first published in 1973, and Good God!: a string of verses to tie up the deity in 1977. In 1985, Smoker recorded ‘Why I am an Atheist’ for the BBC World Service. ‘Why am I an atheist?’, she asked. ‘The short answer is that I cannot accept any of the alternatives. I simply don’t find them believable.’ In print, on lecture platforms, and in broadcasting, Smoker was a tireless advocate of reason and compassion. She also conducted hundreds – if not thousands – of humanist ceremonies.

In an interview with Jim Herrick for the New Humanist in 1991, Smoker responded to the idea that secularist campaigning was purely negative by arguing that:

Everything that is negative has a positive aspect. I suppose it is negative to be against war, but you are for peace. If you are against god-belief then you’re in favour of rationalism. I see it as weeding the ground.

Barbara Smoker published her autobiography, My Godforsaken Life: Memoir of a Maverick, in 2018. She died at Lewisham Hospital on 7 April 2020, aged 96.

An eternity in heaven – that would be hell.

Barbara Smoker

In recognition of her decades-long devotion to humanist campaigning, Barbara Smoker was awarded the Distinguished Service to Humanism Award in 2005. Almost half a century earlier, she had helped to organise the second ever World Humanist Congress, welcoming members of the International Humanist and Ethical Union (now Humanists International) to London. A fearless campaigner for progressive reform, and a forthright defender of freedom in all its forms, Smoker was one of the 20th century’s leading humanist activists, whose remarkable legacy lives on.

Women without Superstition by Annie Laurie Gaylor

Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA, the biological molecule of hereditary information, and cracked the genetic code by which […]

I fear their creed as we have always fearedthe lifted hand against unfettered thought. John Hewitt, ‘The Glens’ in Collected […]

If the basic cause of an unsuccessful marriage is removable, conciliation is the proper procedure. If it is not removable, […]

Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington was an activist, feminist, and humanist, who founded the Irish Women’s Franchise League, and was described by the […]