I have adhered to such of the older traditions as I find adequate for my most lawless and revolutionary passions and moods… And in all my moods I have striven to achieve directness, truthfulness and naturalness of expression instead of an enameled originality.

Claude McKay, Harlem Shadows (1922)

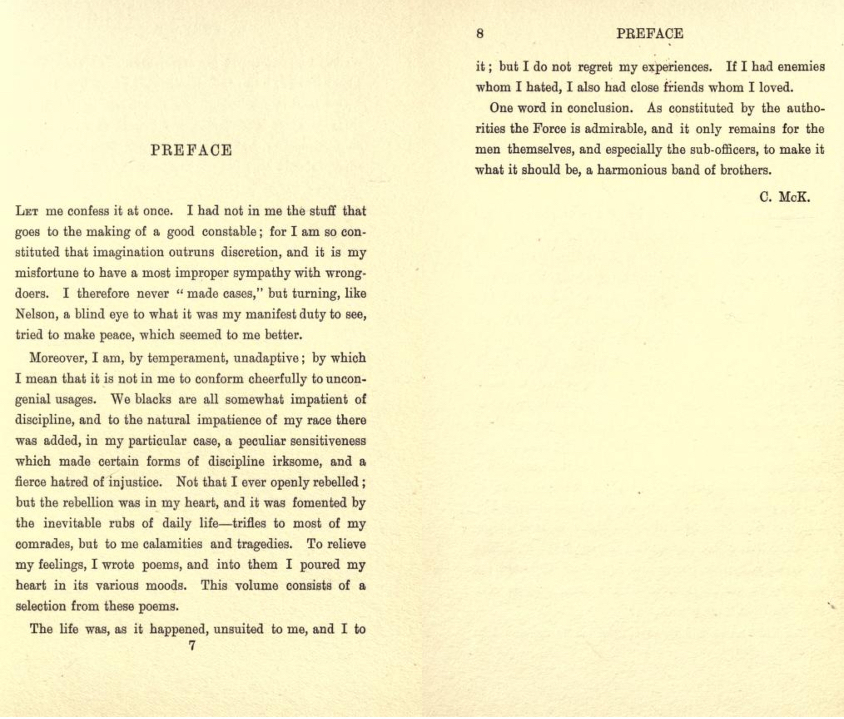

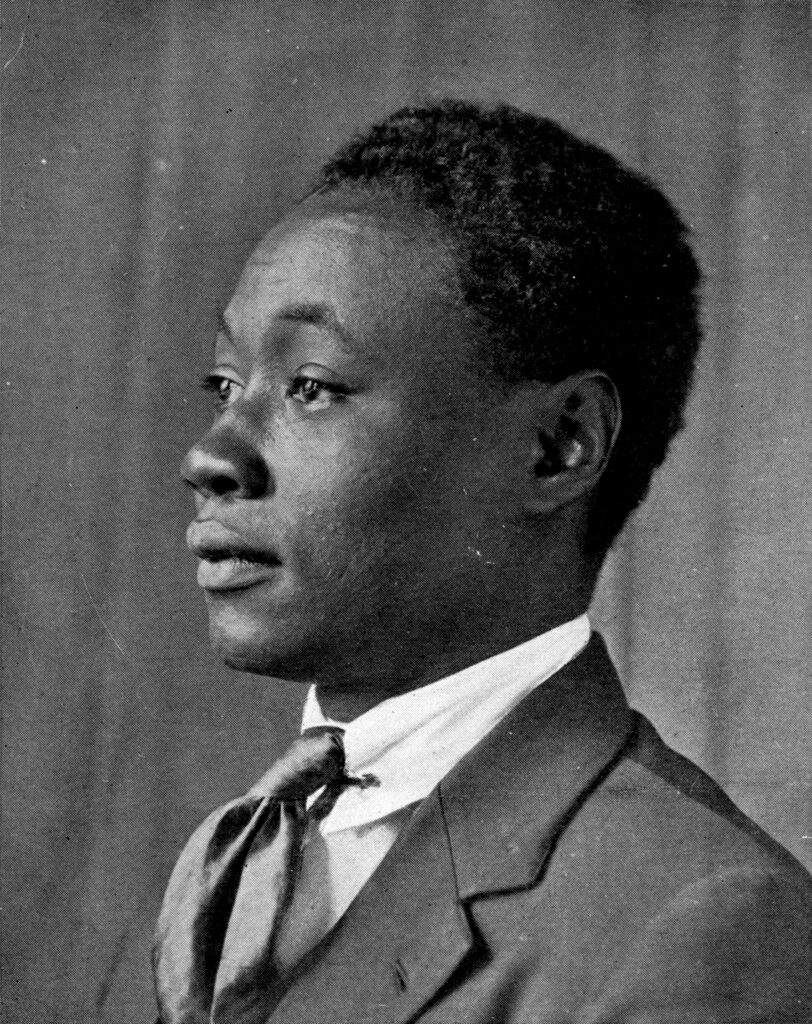

Claude McKay was a Jamaican-born poet and socialist, whose Constab Ballads was published by Watts & Co. in 1912. Though a convert to Catholicism in his final years, McKay was a freethinker for the majority of his life, embodying humanist ideals of rationalism, liberty, and cooperation, and becoming a member of the Rationalist Press Association while in London. In England and abroad, he associated with many of the period’s leading radicals, including socialist suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst. In America, he was a formative influence on the writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Claude McKay was born Festus Claudius McKay in Jamaica in 1889. In his autobiography, A Long Way from Home, he described his childhood as ‘singularly free of the influence of supernatural religion’, imbuing him with a scepticism towards – though an openness to discussions of – theological doctrines. From boyhood, he read widely, including works of science and literature. McKay recalled ‘the discovery of the romance of science’ in T.H. Huxley’s Man’s Place in Nature, and Ernst Haeckel’s The Riddle of the Universe, as hitting him ‘like a comet’. He also took early to writing poetry, which often explored queer intimacy – his first collections being no exception. Written in the first person, Constab Ballads (1912) and Songs of Jamaica (1912) both explore a relationship with a police officer called Bennie.

His acquaintance with Walter Jekyll, an ex-clergyman who had renounced his faith and moved to Jamaica, was formative for McKay’s reading and writing. ‘During those years’, wrote McKay:

…Mr. Jekyll was translating Schopenhauer and I read a lot from his translation. Then he suggested Spinoza’s Ethics, which I read, skipping the mathematical hypotheses, and for a time considered myself a pantheist. Also at that time the Rationalist Press of London was publishing six-penny reprints of Herbert Spencer’s works, which I devoured greedily as they appeared.

Jekyll was interested in African-Caribbean literature, and in 1906 had published Jamaican Song and Story: Annancy Stories, Digging Songs, Ring Tunes, and Dancing Tunes. He supported the publication of McKay’s first collection, Songs of Jamaica (1912), written in Jamaican dialect. In the same year, Watts & Co. published McKay’s second work Constab Ballads.

McKay travelled to America in 1912, attending Tuskegee Institute and Kansas State Teachers College. In 1914, he went to New York, continuing to write, and becoming progressively more activist. It was in 1919 that McKay travelled to London. There, he spent a lot of time at the International Club, where:

For the first time I found myself in an atmosphere of doctrinaire and dogmatic ideas in which people devoted themselves entirely to the discussion and analysis of social events from a radical and Marxian point of view. There was an uncompromising earnestness and seriousness about those radicals that reminded me of an orthodox group of persons engaged in the discussion of a theological creed. Only at the International Club I was not alienated by the radicals as I would have been by the theologians. The contact stimulated and broadened my social outlook…

In early 1920, McKay began working for Sylvia Pankhurst’s newspaper The Workers’ Dreadnought. He described Pankhurst as having ’a personality as picturesque and passionate as any radical in London.’ Another friend was writer, philosopher, and founder of the Cambridge Heretics C.K. Ogden, who published some of McKay’s poems in the Cambridge Magazine.

McKay’s most influential collection, Harlem Shadows, appeared in 1922, and was a founding text of the Harlem Renaissance (an African American intellectual and cultural revival). Other leading lights of the movement, including Zora Neale Hurston and Countee Cullen, were similarly humanist in outlook to McKay. Another Harlem figure, and personal friend of McKay’s was Hubert Harrison, an influential activist, internationalist, and humanist.

Up against laws put in place by the fervently religious Anthony Comstock prohibiting the ‘vice’ of disseminating LGBT content in writing, authors such as McKay were under threat of criminal prosecution for their work. Yet, McKay did not hide his bisexual desires and is speculated to have had a sexual relationship with the writer John ‘Buffy’ Glasco while living in Paris in 1929. His sexuality is imbued in his writing, such as the scene in McKay’s Home to Harlem (1928) where ‘the dark dandies were loving up their pansies’.

I have nothing to give but my singing. All my life I have been a troubadour wanderer, nourishing myself mainly on the poetry of existence. And all I offer here is the distilled poetry of my experience.

Claude McKay, A Long Way from Home (1937)

McKay was a freethinker from childhood, and turned his pen in poetry and fiction towards sometimes scathing critiques of Christianity. Like other writers of his generation, including W.E.B Du Bois, McKay was outspoken in his criticism of Christianity’s role in racial oppression, and the hypocrisy of Christians who failed to condemn it.

Claude McKay is one of the historical figures featured in Picturing Nonconformity: LGBT Humanist Heritage, created for the 45th anniversary of LGBT Humanists in 2024. Explore the exhibition.

Francis Crick discovered the structure of DNA, the biological molecule of hereditary information, and cracked the genetic code by which […]

As well as being one of the most distinguished musicians of his time, he was, like Sir Hubert Parry before […]

The object of this Society is: To increase the knowledge, the love, and the practice of the right. Its bond […]

Love is a kind of courage, and, in the hearts of the man and woman who will here wed, there […]