…having now exceeded the age of three score years and ten, I would say that up to the present I have been a very happy and fortunate man in having lived so long… in having a happy family life, and in having been given the opportunity of serving in a state of life to which I had never expected to be called.

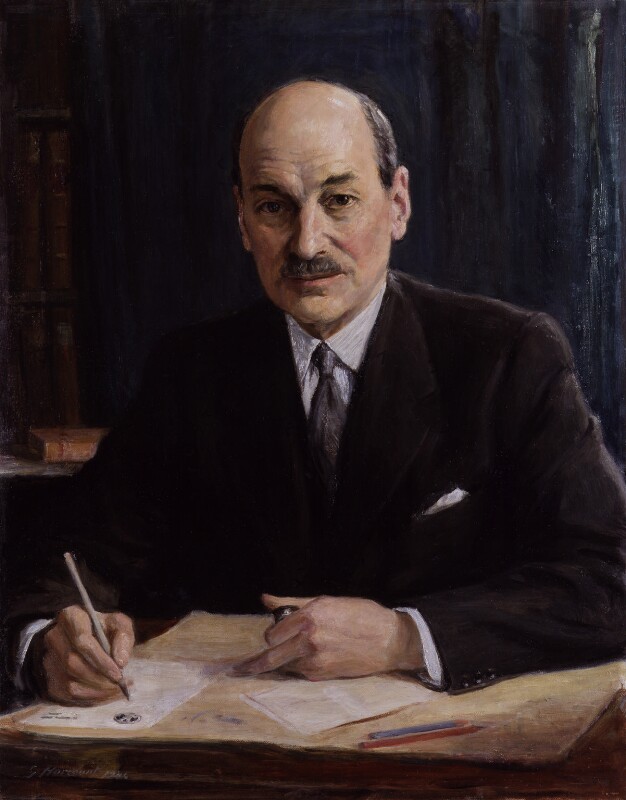

C.R. Attlee, As It Happened (1954)

Clement Attlee was one of at least three non-religious 20th century Prime Ministers, and one whose socialist and humanist values underpinned his commitment to implementing sweeping reforms in social welfare. Described by historian R.C. Whiting as an ‘unobtrusive atheist,’ Attlee firmly believed in ‘ethics’ without ‘mumbo-jumbo’, and earned a reputation as a principled, decisive, yet modest politician. He had many friends and colleagues who were active in the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), including Ramsay MacDonald and Harry Snell, who Attlee described as ‘a great citizen of the world and a very great gentleman’.

Clement Richard Attlee was born in Putney, London on 3 January 1883, the seventh of eight children. His father was a solicitor, and Attlee described the family as ‘happy and united’. Educated first at home by his mother, he later went to schools in Hertfordshire, and then to University College, Oxford, where he studied history. On graduating, Attlee initially drifted, without much enthusiasm, towards law. However, a visit to a Stepney Boys’ club in 1905 dramatically altered his course. Continuing a family tradition of ‘social service’, he became the club’s resident manager in 1907, later expressing his conviction that:

One learns much more of how people in poor circumstances live through ordinary conversation with them than from studying volumes of statistics.

Like William Beveridge, whose 1942 Social Insurance and Allied Services report provided the blueprint for the welfare state, Attlee was markedly influenced by witnessing the poverty of London’s East End. Both men spent time at Toynbee Hall settlement, and both eschewed careers in law in favour of active reform. Attlee’s political views were also shaped by his experiences in the East End, and he joined the Independent Labour Party in 1908. Following military service in the First World War, Attlee decisively entered politics. He became Mayor of Stepney in 1919, MP for Limehouse three years later, and rose quickly through the ranks of the Labour Party, becoming leader in 1935. He would remain so for two decades.

During the Second World War, Attlee served as Deputy Prime Minister in Winston Churchill’s coalition government, before being elected Prime Minister in a landslide victory for Labour in 1945. As Prime Minister, he achieved far-reaching innovations in social welfare, enlarging and improving social services and the public sector in post-war Britain. Under Attlee’s leadership, a National Health Service was introduced, as was a scheme of social security with the National Insurance Act of 1946. One fifth of the British economy was nationalised, including coal, electricity, and railways. Other significant legislation included the Town and Country Planning Act 1947, the Children Act 1948, the Nurseries and Child-Minders Regulation Act 1948, and the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. Attlee’s government delivered on almost all of their manifesto pledges, and he has regularly been ranked as one of Britain’s most effective Prime Ministers. Attlee continued to lead the Labour Party until 1955.

Attlee’s relationship with religion could perhaps be best described as ambivalent. Although he acknowledged the ‘ethics’ of Christianity, he did not accept any of what he described as its ‘mumbo-jumbo’. Indeed, his entry into politics and his lifetime of service were motivated by a sense of social conscience inherited from his parents, and consciously divorced from religious notions. According to Attlee’s biographer, Kenneth Harris:

He fully shared his parents’ sense of moral and social responsibility, with its emphasis on a high standard of duty towards the poor and sick; this feeling became… the basis of his future socialism.

Although Attlee did not believe in God, and described himself as ‘incapable of religious experience’, he was close to many professing Christians, and was not critical or dismissive of religion. He concluded:

It worked for many of those I most liked and admired, so it was nothing to laugh at or asperse. But it meant nothing to me one way or the other.

Many among Attlee’s friends and colleagues were members of the early organised humanist movement. George Lansbury, his predecessor in the role of Labour Party leader, had been involved with the East London Ethical Society during the 1890s, and Attlee’s colleague Ramsay MacDonald had played a prominent role in the Union of Ethical Societies in its formative years. It was Harry Snell, however, Labour MP and President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) 1931-2, to whom Attlee was closest. Speaking at Snell’s memorial service, led by H.J. Blackham, Attlee commended ‘a long life [devoted] to the service of humanity’. He added: ‘No man I have known had less care of himself or more for others’.

In retirement, Attlee travelled widely and wrote regularly. He died on 8 October 1967, three years after his wife, Violet, with whom he had enjoyed a long and supportive marriage. Attlee was cremated, and his ashes placed in Westminster Abbey.

With William Beveridge and Nye Bevan, Attlee was one of a trio of non-religious figures who pioneered the modern welfare state. Like them, Attlee was motivated by an enduring sense of social responsibility, which underpinned his socialism and his humanism. In a tribute printed in The Times after Attlee’s death, Conservative politician Edward Heath described him simply, and effectively, as ‘a man who cared deeply about people’.

In Humanists UK’s 2016 Holyoake Lecture, Owen Jones listed Attlee among those historic humanists whose examples can still inspire us today. He said:

Our history abounds with great humanists who helped build a society that was more free, just, creative and informed, like Marie Curie and William Beveridge, like Mary Wollstonecraft and Clement Attlee, like George Eliot and Stephen Hawking. Here is a tradition we should feel proud to stand in… Many of the noble aims of humanism may seem under threat today. But this age, too, will pass. A politics of humanism can help build a world that is free, just and equal. It is not inevitable – but it is necessary, and we all have a role in creating it.

Owen Jones, ‘Age of Extremes’ (adapted text of the 2016 Holyoake Lecture), printed in the New Humanist, Spring 2017

Clement Attlee | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Clement Attlee | National Portrait Gallery

Attlee by Kenneth Harris (1982)

As It Happened by C.R. Attlee (1954)

The radical publisher Edward Truelove found himself in court more than once defending freedom of belief and expression. He believed, […]

Humanists International was formed in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU): a federation of the American Ethical […]

In common with other humanists, I believe that the only possible basis for a sound morality is mutual tolerance and […]

I suggest that the assembly we really want is an act of celebration, rather than worship. There is value in […]