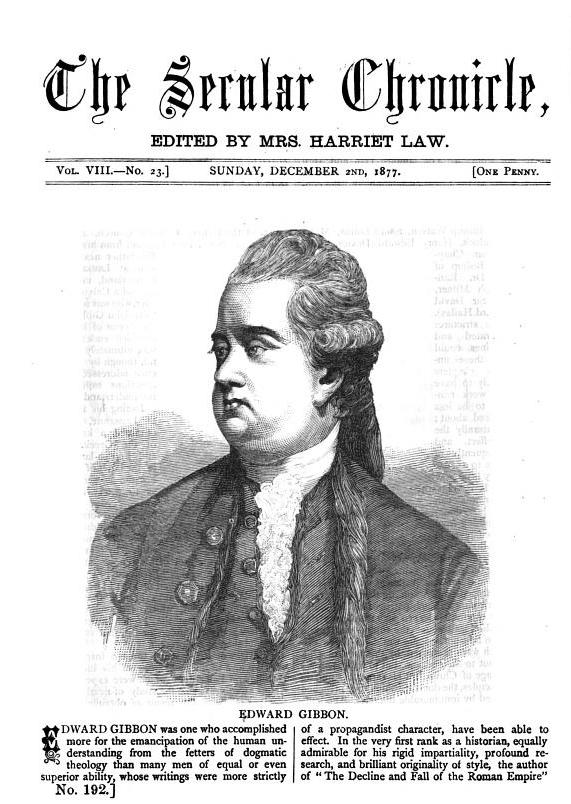

“Yet, upon the whole, the History of the Decline and Fall seems to have struck root, both at home and abroad, and may, perhaps, a hundred years hence still continue to be abused.” So Gibbon wrote in the calm confidence of immortality; and let us confirm him in his own opinion of his book by showing, in the first place, that it has one quality of permanence—it still excites abuse.

Virginia Woolf, ‘The Historian and “The Gibbon“‘ (1937)

Edward Gibbon was a historian whose principal work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published 1776-88), sent shockwaves through religious orthodoxy. In it, he used classical scholarship to refute many of the prevailing myths surrounding the spread (and suppression) of Christianity in the Roman world, emphasising the human – rather than divine – influence on its origins and growth.

Gibbon’s significance to the development of humanist thought lies in his throwing open to dispassionate historical analysis the ‘sacred’ narrative of Christianity. In this, he was distinctly of the Enlightenment: led by principles of science and rationalism to produce a work of history still lauded centuries later.

Edward Gibbon was born in Putney in 1737, the son of Edward Gibbon, a farmer and MP. A sickly child himself, six siblings born after him died in infancy, and his mother in 1847, when Gibbon was ten. The financial carelessness of his father until his death in 1770 meant that Gibbon’s material comfort was up and down over the course of his life, and his early education similarly so. He was, however, a voracious reader from a young age. Gibbon was sent to Oxford University at 14, which he recalled in later years as decadent and neglectful of both discipline and education, but a conversion to Catholicism while there startled his father into sending him to Switzerland. In Lausanne, under the influence of a kindly new guardian, Gibbon renounced the Catholic faith and supposedly returned to Protestantism, although he was – and remained – a clear sceptic.

Gibbon’s propensity towards questioning was clearly evident from his boyhood. In his Autobiography, he recalled a fondness for ‘religious disputation’, confounding his aunt with ‘objections to the mysteries which she strove to believe’. Of his own examinations of religion, Gibbon wrote that ‘the love of truth and the spirit of freedom directed my search’. As such, he ‘stept aside into every path of inquiry which reading or reflection accidentally opened’. Historian J. M. Robertson, one of the Union of Ethical Societies’ (now Humanists UK’s) first presidents, noted in his Pioneer Humanists (1907), that thanks to his youthful explorations of theology and devotedness to research, Gibbon

combined thorough knowledge with perfect detachment of spirit. In him, the cessation of fear of the Lord constituted a beginning of wisdom.

The work which proved this most, and elicited significant controversy, was Gibbon’s six volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the first part of which was published in 1776. In its infamous fifteenth and sixteenth chapters, which detailed the rise and consolidation of the Christian religion, his perceived hostility towards Christianity drew the ire of many among the devout. Sitting as they did within the impartial and academically rigorous work as a whole, Gibbon’s descriptions of Christianity:

… gave offence from the very beginning of chapter 15, by ostentatiously setting aside any explanation for the rise of Christianity as the work of divine providence, and focusing instead on five ‘secondary causes,’ including the ‘intolerant zeal’ of the Christians… their beliefs in the immortal soul and in miracles, their pretension to purity of morals, and their discipline, which quickly made the Church an independent state within the Empire.

With careful use of irony, Gibbon cast into doubt the reality of miracles and the unquestioned ‘truth’ of Christianity. The rise of the religion as seen in Gibbon’s History was brought about by man, and was neither inevitable nor providence-ordained. Having penned stinging statements like ‘it was not in this world that the primitive Christians were desirous of making themselves either agreeable or useful,’ Gibbon was not oblivious to the work’s controversial character. When he shared the first part with David Hume in 1776, the philosopher warned that it was ‘impossible to treat the subject so as not to give ground of suspicion against you, and you may expect that a clamour will arise.’ He was right, and Gibbon was prompted to write a response in 1779. His Vindication of Some Passages in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Chapters, though, was largely provoked not by criticisms of his religious infidelity, but of his accuracy as a historian.

Gibbon died on 16 January 1794 in London, the ramifications of the French Revolution having seen renewed attacks on the History and its undermining of traditional beliefs. He was buried in the church at Fletching, Sussex, his memorial inscription including the words:

In his personal character there was a reasonableness of mind joined with liberal sentiments. In his conversation charm was joined agreeably to deep seriousness.

Writing in The Secular Chronicle one hundred years after the publication of his History, Harriet Law described Gibbon as having ‘accomplished more for the emancipation of the human understanding from the fetters of dogmatic theology than many men of equal or even superior ability’. For J. M. Robertson, histories of religion before him represented ‘the chaos of tradition and miracle from which Gibbon helped to effect our deliverance.’ Today, Gibbon’s scholarship is viewed as ‘representative of the Enlightenment’s commitment to understanding as well as to criticism, and not least to understanding the power of religion.’ In the words of Edward Clodd, delivering the Conway Memorial Lecture in 1916:

It remains to his immortal credit that, once and for all, he cleared the way to subject Christianity to the same method of investigation which is since adopted in every field of research, and this at a time when the science of comparative theology was yet unborn… and, covertly denying the supernatural origin of Christianity, opened the road to proving that its progress, or whatever else we choose to call it, is explicable by human agencies, and human agencies alone.

Gibbons’ stature as a supreme prose stylist is also another source of his lasting influence. Diverse figures such as Prime Ministers Winston Churchill (who was similarly scathing of Christianity) and humanist writer Isaac Asimov all credit Gibbon’s writing as an influence on their style and ideas. Catholic writers such as Evelyn Waugh celebrated his writing and derided his views with equal intensity. He was also a significant influence on Virginia Woolf, whose novels and essays treat him as almost the symbol of a divided era – torn between two ways of thinking about history, religion, and philosophy.

Humanists today are inheritors of this tradition of sceptical observation, critical evaluation of evidence, and an emphasis on the role of humankind in advancing ideas. As such, although his own private beliefs remain the subject of debate, Gibbon’s influence on the freethinkers and humanists who came after him cannot be underestimated.

All moral and political wisdom should tend mainly to this, the just distribution of the physical means of happiness. William […]

Why not agree to differ about the questions which no one denies to be all but insoluble, and become allies […]

How strange is the lot of us mortals! Each of us is here for a brief sojourn; for what purpose […]

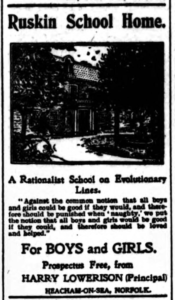

The Ruskin School Home was founded by socialist writer and teacher [Harry] Bellerby Lowerison (1863–1935) in Norfolk in 1900, following […]