Because no one will believe without a splash from a font

Edwin Morgan, ‘Pelagius’ (2002)

Their baby will howl in eternal cold, or fire,

And no one will suffer the elect without merit

To lord it over a cringing flock, and no one

Is doomed by Adam’s sin to sin for ever,

And who says Adam’s action was a sin,

Or Eve’s, when they let history in.

Edwin Morgan was a Glaswegian poet and translator, one of the best-known and best-loved Scottish writers of the 20th century. His work is celebrated both for its wide range of styles and themes and for the humane and progressive causes with which it engages. Amongst other things, Morgan is one of the great atheist poets of the twentieth century, interested in defining and celebrating human consciousness without recourse to religious metaphysics, notably in response to the challenges posed by ideas of artificial and animal intelligence. As a gay poet, his work also touches on themes of queer identity and religious bigotry.

We are alive

Edwin Morgan, ‘From A Nursing Home’ (2010)

With whatever equanimity we can muster

As time bites and burns along our veins

Edwin Morgan was born in 1920, the only child of middle class parents based in the west end of Glasgow. Morgan’s upbringing was loving but strict, following the tenets of Church of Scotland Presbyterianism. As a teenager he became interested in anarchist and Marxist politics and in the contemporaneous art movement of Surrealism. A sense of enmity to what he later called ‘the bad old rhetoric’ of the Kirk, that ‘tries to stamp out every glow of charity and change, most wrong,/ when it thinks most loudly it is most right’, set in early (‘The Flowers of Scotland’, 1969).

Morgan entered the University of Glasgow as a language student in 1937. His studies were interrupted, however, by a period of service in the Royal Army Medical Corps, with whom he served in North Africa and the Middle East from 1940 to 1946. Originally registering as a conscientious objector, the poet’s anti-fascist ideals eventually saw him willing to carry a stretcher but not a gun. He graduated in 1947 but returned to Glasgow University almost immediately to take up a post as a lecturer, and would stay in the same department until 1980, when he retired as a professor.

The 1950s was a decade of creative frustration and emotional isolation, partly reflecting the poet’s sense of social ostracisation as a gay man in a conservative Christian society. As the 1960s dawned, however, Morgan’s life and writing took on a new tenor as he embraced the spirit of social and sexual liberation of the counter culture and the demise of religious homogeneity in Scottish culture, as well as the intellectual and creative challenges of computer technology, cybernetics, and space travel. A formally and linguistically experimental poet, Morgan was influenced by the socialist literary-modernist heritage of Europe and Russia, in particular the Soviet-revolutionary poetry of Vladimir Mayakovsky. By contrast, he baulked at what he saw as the reactionary conservatism of the Anglo-American modernist canon, represented by figures such as Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot.

Morgan’s breakthrough 1968 collection The Second Life covered enormous ground in formal and thematic terms, notably engaging with ideas of artificial and robotic intelligence through a series of playful ‘Computer Poems’, and other poems written from non-human perspectives. These pieces, though often comic in tone, had significant philosophical implications, querying notions of consciousness as something uniquely human, exalted and God-given. There were also poems about space travel which explored the material realities of an infinite universe, and searing poems of social commentary, such as ‘Glasgow Green’, which described, according to the poet himself, a ‘homosexual rape’ and was based on several incidents from his own life (‘Transgression in Glasgow: A Poet Coming to Terms’, in De-centring Sexualities: Politics and Representations beyond the Metropolis, eds Richard Phillips, Diane Watt and David Shuttleton [2000]).

Further successful collections such as From Glasgow to Saturn (1973) and Poems of Thirty Years (1982) established Morgan as a celebrated figure within Scottish literary culture. But he only publicly announced his sexuality in 1990, marking both his 70th birthday and Glasgow’s stint as European City of Culture. Following this revelation, Morgan became a figurehead for LGBTQIA+ rights in his home country, notably publishing several poems on the theme of religious, intellectual, and sexual freedom in his 2002 collection Cathures, composed during his time as poet laureate of his home city. For example, there was the scabrous protest poem ‘Section 28’, which dealt with religious opposition to the repeal of laws banning the ‘promotion of homosexuality’ in schools. ‘Your favourite sound-bite, gay perversion,/ Is not in my New Authorized Version./ I think you ought to buy a copy: Squeeze it out of Souter’s poppy’. (The evangelical businessman Brian Souter had donated a million pounds to the campaign opposing the repeal).

In 2000, Morgan’s trilogy of plays on the life of Jesus Christ, AD, was debuted and published. In these works the prophet appears as a complex, human figure, sexually active, with a child by an unmarried Greek woman, and with an anti-colonial freedom fighter for a brother. Pastor Jack Glass and a flock of evangelical Christians protested the premiere at Glasgow’s Tramway, throwing 30 pieces of silver in the foyer to connect Morgan’s work with Judas’s betrayal of Jesus.

In 2004, Morgan became the Scottish Makar or national poet. He died in 2010, proclaiming in one of his final poems, ‘From A Nursing Home’ (2010), that he had never dwelt on ‘First and last things’, such as the possibility of an afterlife. The poem rather surmises, with brilliant poignancy, ‘we are alive/ With whatever equanimity we can muster/ As time bites and burns along our veins’.

Edwin Morgan is perhaps the most famous and most widely admired Scottish poet of the 20th century. This is partly because his work is so defined by its embrace of the new – in politics, society, technology, and popular culture – in a country whose writers have often embraced a ruralist vision of the past. No brittle atheist evangelist, Morgan retained a great interest in and respect for global religions, and was particularly excited by histories of radical and dissenting faith. But no other figure in Scottish literary culture stands so clearly for the shift from religious conservatism to progressive secularism that marks the country’s late-20th-century history. The poem quoted above, ‘Pelagius’ (2002), in which Morgan compares himself to a fourth-century theologian who refuted the doctrine of original sin, perhaps sums up more than any other his sense of his own legacy:

I do not even need to raise my arms,

My blessing breathes with the earth.

It is for the unborn, to accomplish their will

With amazing, but only human, grace.

By Greg Thomas

This article draws from Greg’s 2019 book Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and Scotland as well as several articles on Morgan’s poetry and art, and research towards a forthcoming, posthumous edition of Morgan’s concrete, visual, and sound poetry, A Home in Space, which he is co-editing with Julie Johnstone.

Edwin Morgan, Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet, 1990).

– Collected Translations (Manchester: Carcanet, 1996).

– Nothing Not Giving Messages: Reflections on his Work and Life, ed. Hamish Whyte (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1990).

– The Edwin Morgan Twenties [box set of five volumes of selected poetry, available individually] (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2020).

Eleanor Bell and Linda Gunn, eds, The Scottish Sixties: Reading, Rebellion, Revolution? (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2013).

Robert Crawford and Hamish Whyte, eds, About Edwin Morgan (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990).

James McGonigal, Beyond the Last Dragon: A Life of Edwin Morgan (Dingwall: Sandstone, 2010).

Colin Nicholson, Edwin Morgan: Inventions of Modernity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002).

Alan Riach, ed., The International Companion to Edwin Morgan (Glasgow: Association for Scottish Literature, 2015).

Greg Thomas, ed., Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and Scotland (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2019).

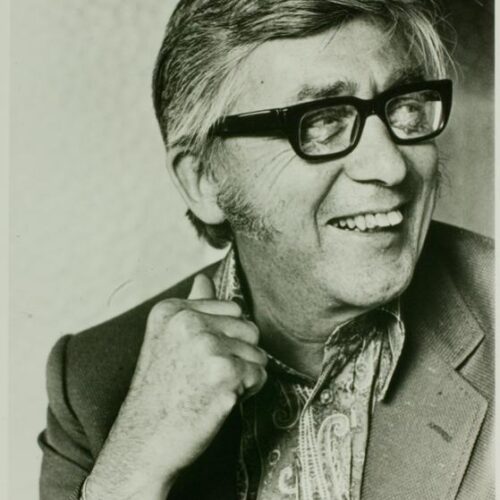

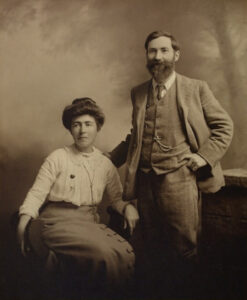

Main image: Courtesy of the Edwin Morgan Trust

…having now exceeded the age of three score years and ten, I would say that up to the present I […]

The hard anger she felt at the cruelty she encountered was always rooted in a deep tenderness for vulnerable humanity. […]

Positivism is a philosophical system based on the writings of French thinker Auguste Comte, which flourished from the 1830s onwards. […]

A distinctively Edwardian rationalist radical, he himself agreed that he was a crank – ‘a small instrument that makes revolutions’. […]