In order to find meaning to one’s life, one must find a meaning in the life of the [human] race. And this meaning we find in the high-light points of history, in the significant turns, when mankind, in the person of some of its most excellent representatives, pressed forward toward self-knowledge. For that is progress – increasing self-revelation, the discovery of the powers inherent in human nature through the exercise of the powers, the knowledge of them.

Felix Adler in the New York Times, 15 Nov 1926

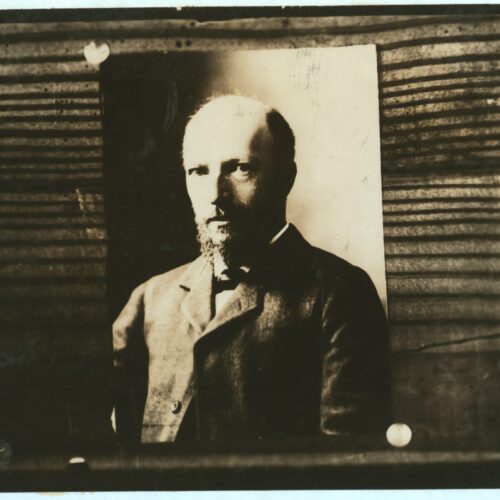

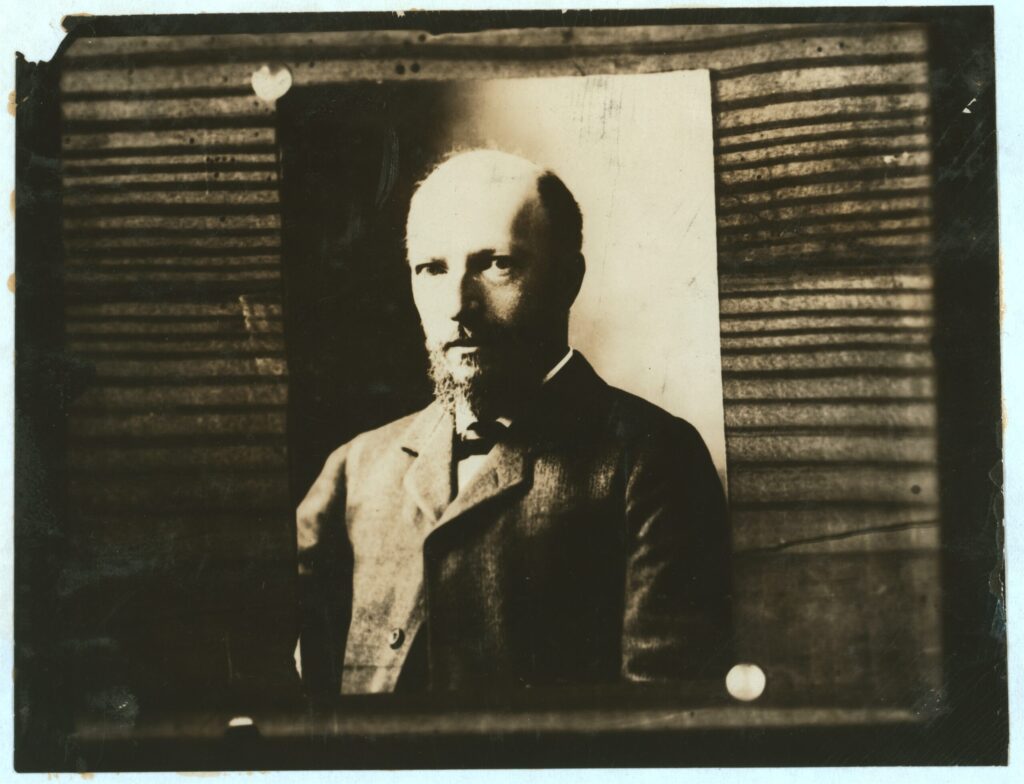

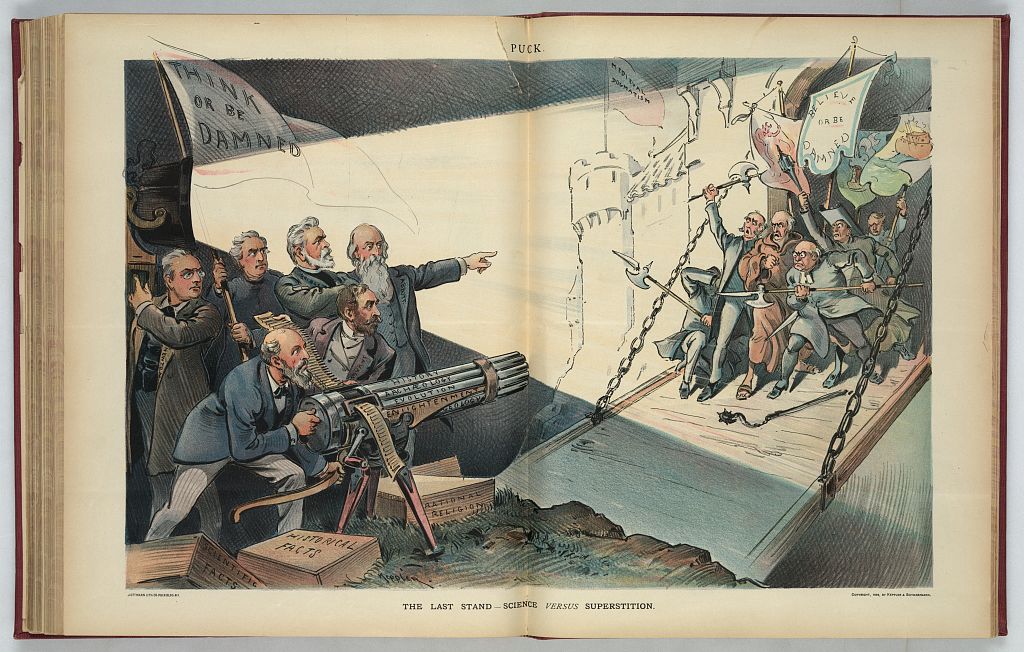

As the founder of the Ethical Culture movement, Felix Adler laid the foundations for what would become organised humanism. Adler’s focus lay on developing our notion of what is right, and acting on our ethical beliefs through good deeds, without reference to gods or theology. In his own life, Adler was involved in a number of innovative efforts toward social reform, including in areas of education, welfare, housing, medical care, and the rehabilitation of prisoners. Adler’s emphasis on morality, reform, and human agency continue to underpin the humanist approach today.

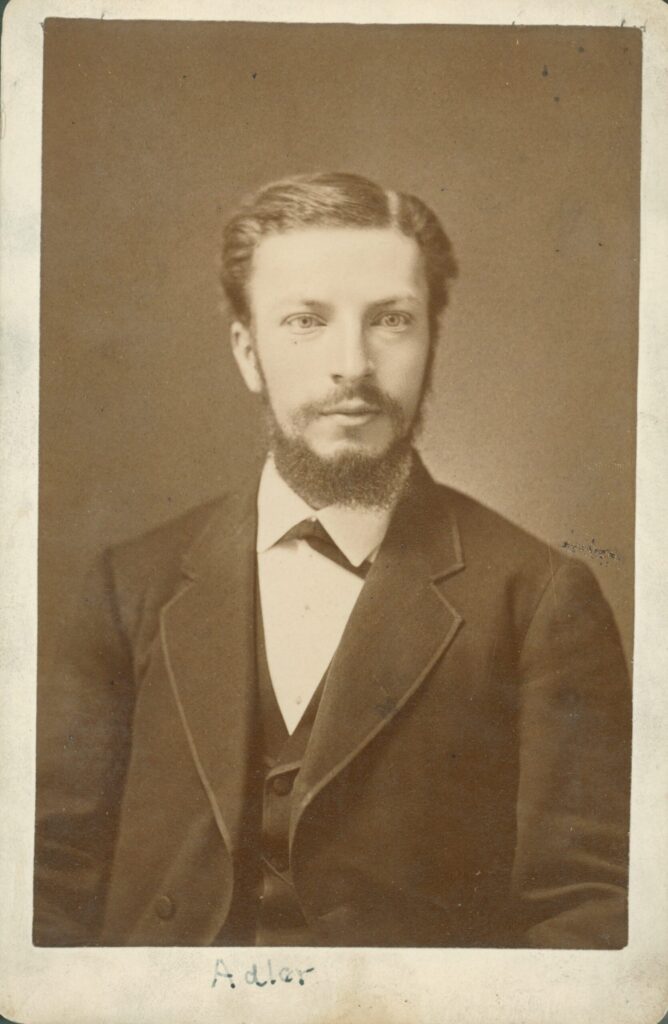

Born in Germany in 1851, Felix Adler was the son of a rabbi. The family moved to New York City when Adler was six, his father taking up the rabbinate of Temple Emanu-El, one of the leading Reform Jewish congregations in the country. Adler received an excellent education, with a ‘heavy emphasis in the classics and languages’. He also accompanied his mother on charitable visits in the community, witnessing poverty and its impacts first hand. Alongside an atmosphere of religious inquiry and social responsibility, Adler was raised with an appreciation for music, art, and literature. All of these elements would combine in the philosophies of his later life.

In 1870, Adler graduated from Columbia College and in 1873 received his doctorate in philosophy at Heidelberg. That year, he became the Chair of Hebrew and Oriental literature at Cornell University. In October of 1873, he was invited to deliver the sermon at the Temple Emanu-El, but Adler’s progressive vision – ‘not of the creed but of the deed’ – shocked his father’s congregation. He called upon them to:

… discard the narrow spirit of exclusion and loudly proclaim that Judaism was not given to the Jews alone, but that its destiny [is] to embrace in one great moral state the whole family of men.

In the development of this new, inclusive and practical ‘religion’, Adler was influenced by two key figures: Kant and Emerson. From Kant, he absorbed an idea of the impossibility of proving the existence of god through reason, and the possibility of developing a sense of morality distinct from a belief in god. In 1875, Adler met Ralph Waldo Emerson, and was introduced to the concept of ‘Free Religion’. Adler underplayed the Emersonian in his own philosophy, but the ideas of an ethical religion and focus on self-reliance demonstrate the influence on Adler – as on so many others of his generation – of Emerson.

The following year, on 15 May 1876, Adler gave the first lecture for what would become his Society for Ethical Culture. Speaking to an assembly at the Standard Hall in New York City, many of whom had been present at for his Temple Emanu-El sermon, Adler further elaborated on the ideas he had first introduced there:

We propose entirely to exclude prayer and every form of ritual… it is my dearest object to exalt the present movement above the strife of contending sects and parties and at once to occupy that common ground where we may all meet… for purposes in themselves lofty and unquestioned by any… We shall at all times respect every honest conviction… Diversity in the creed, unanimity in the deed.

This began a series of lectures by Adler, inaugurating what was formally established as the Society for Ethical Culture in February 1877. Adler’s concern with good deeds animated the group, and over the next decade they introduced a number of innovative social enterprises, including a free kindergarten, a district nursing programme, a tenement house building company, and the Workingman’s School. The movement grew too, with new societies emerging across the country.

In 1880, Adler married Helen Goldmark, who was actively involved in the organisation of the Society for Ethical Culture, and its social works. The couple had five children: Waldo, Eleanor, Lawrence, Margaret, and Ruth.

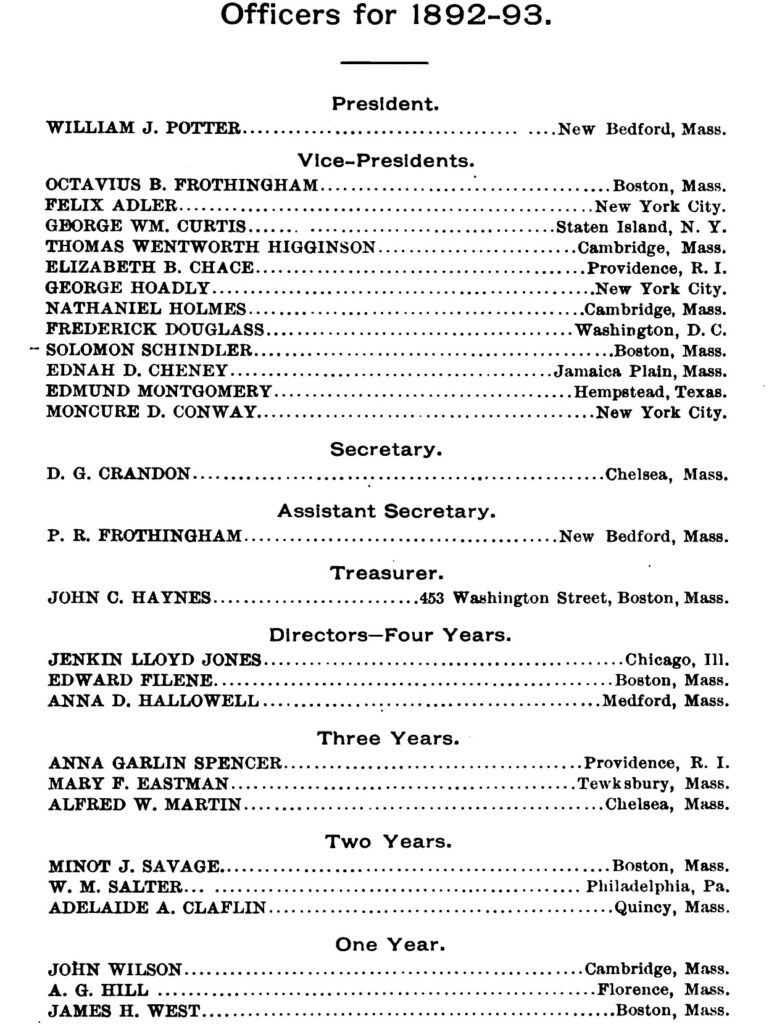

Between 1878-82, Adler was the President of the Free Religious Association – founded in 1866 following a struggle between the conservative and liberal strands of Unitarianism, and numbering among its members Ralph Waldo Emerson, Lucretia Mott, and Julia Ward Howe. The objects of the Association were ‘to encourage the scientific study of religion and ethics, to advocate freedom in religion, to increase fellowship in spirit, and to emphasise the supremacy of practical morality in all the relations of life.’ Adler resigned in 1882, frustrated by the Association’s perceived lack of action in practical works and improved morality.

You may be sure that my resignation from the Presidency of the Free Religious Association does not imply a change of conviction. It implies the opposite; that the advocacy of my opinions employs all my time and interest. I have the greatest respect for those who compose the Free Religious Association, but the association itself has disappointed me by its slowness and apparent lack of vitality.

That the Association saw itself as a ‘voice without a hand’, was certainly less than the active and reforming quality of Adler’s ideals. However, he remained a Vice President of the Association, listed alongside Frederick Douglass and Moncure Conway in a pamphlet celebrating its 25th annual convention.

In 1889, the American Ethical Union was formed, federating the US ethical societies. The following year, Adler founded the International Journal of Ethics, to which many notable members of the English societies contributed throughout the following years. In 1896, the year the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK) was founded, Adler was actively involved in the formation of the International Union of Ethical Societies. A sense of internationalism was always part of both the US and UK Unions, and it was from an idea of Adler’s that he and Gustav Spiller established the first Universal Races Congress in 1911.

In addition to his role in the Ethical Culture movement, Adler enacted his values through a number of other positions, including as Professor of Social and Political Ethics at Columbia University, as Chairman of the National Child Labor Committee (1904-1921), and on the committee of the Civil Liberties Bureau (today the ACLU).

Felix Adler died 24 April 1933, and was lauded by his admirers as an ‘inspiring guide to a better life for man’, who had ‘the unflinching courage, often in the face of long-established tradition and stubborn opposition, to fight for the practical applications of his ideals’.

He made in his generation a notable contribution to the ethical life, personal and social, of this country. Regardless of creed, all good citizens will mourn a common loss.

Dr Harry Emerson Fosdick

As the founder of Ethical Culture, Adler’s influence on organised humanism was significant on a worldwide scale. Stanton Coit, who pioneered the federation of ethical societies in the UK, took his lead from Adler, and was also inspired by his work among the New York City tenements in establishing his ‘neighbourhood guilds’. The kindergarten founded by Adler when he was just 24, expanded and developed, and exists today as the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. It retains a ‘commitment to ethical education and progressive practice’, drawing on Adler’s belief that ‘education must change with the change of the world’.

Adler’s lectures, writings, and acts as leader and founder of Ethical Culture and in his own life embodied the values of humanism. His emphasis on a lived and active humanist philosophy, can be seen in the works of the Humanist Housing Association, Humanist Care, and the advocacy work of Humanists UK today.

The attainment of the greatest possible amount of social happiness I take to be the noblest of human aims; the […]

There is no one who will deny the value and importance of truth, but how is it to be ascertained, […]

The hard anger she felt at the cruelty she encountered was always rooted in a deep tenderness for vulnerable humanity. […]

If after this survey of the nature of illusions and delusions, we turn again to religious doctrines, we may reiterate […]