A cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant and dignified in every relation of life, and who bore an overwhelming sorrow with more than the patience of Job.

Ernestine Mills on Ford Madox Brown in The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields (1912)

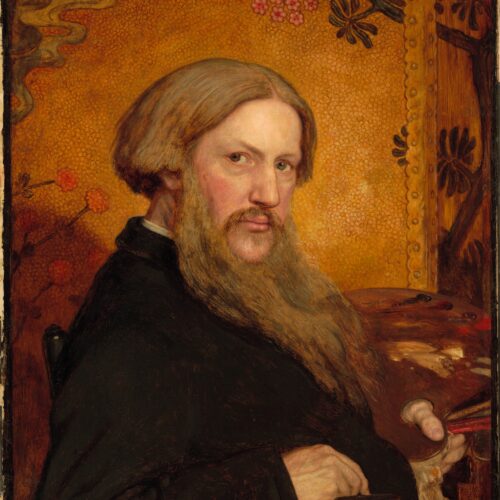

Ford Madox Brown was an artist, designer, and agnostic; a man ‘whose celebrity’, wrote The Times, ‘was by no means equal to his personal and professional worth’. Closely associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as well as with William Morris and Moncure Conway, Brown was part of a circle devoted to art, as well as to freethought in religion and politics. Brown’s funeral, conducted by Conway, was non-religious (as his son’s had been two decades earlier), prefiguring the humanist ceremonies of today.

Ford Madox Brown was born on 16 April 1821 in Calais, France. Most of his life was marked by the same straitened circumstances in which he was raised, but the early talent he displayed for art was nurtured. In spite of an inconsistent formal education, a 14 year old Brown began his studies in art in Bruges, and later in Ghent and Antwerp. He arrived in London in the 1840s and became acquainted with members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Dante Gabriel and William Michael Rossetti – the latter sharing Brown’s own agnosticism. Although never a financial success, Brown retained a lifelong commitment to art, his own and others’, undertaking commissions and staging a Pre-Raphaelite exhibition in 1857. He became an accomplished designer of furniture and stained glass, and was a partner in William Morris’ firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkener & Co. from its origins in 1861.

A portrait of Brown’s humanism emerges from the memoir of Frederic Shields, written by longtime ethical society member Ernestine Mills. In her Life and Letters of Frederic Shields, Mills describes Ford Madox Brown as ‘a cheerful and reverent Agnostic, whose whole life was one of unselfishness and devotion to lofty aims, who was tolerant and dignified in every relation of life’. Brown was a close friend of pioneering humanist Moncure Conway, who conducted the non-religious funerals of both Brown and his son – precursors of today’s humanist ceremonies. Of Ford, Conway wrote:

With Ford Madox Brown I was on terms of particular intimacy because of his sympathy with my religious heresies. I assisted at the marriage of his daughters (one to Franz Hueffer, the musical critic, another to William Rossetti), and I conducted the funerals of his son and himself.

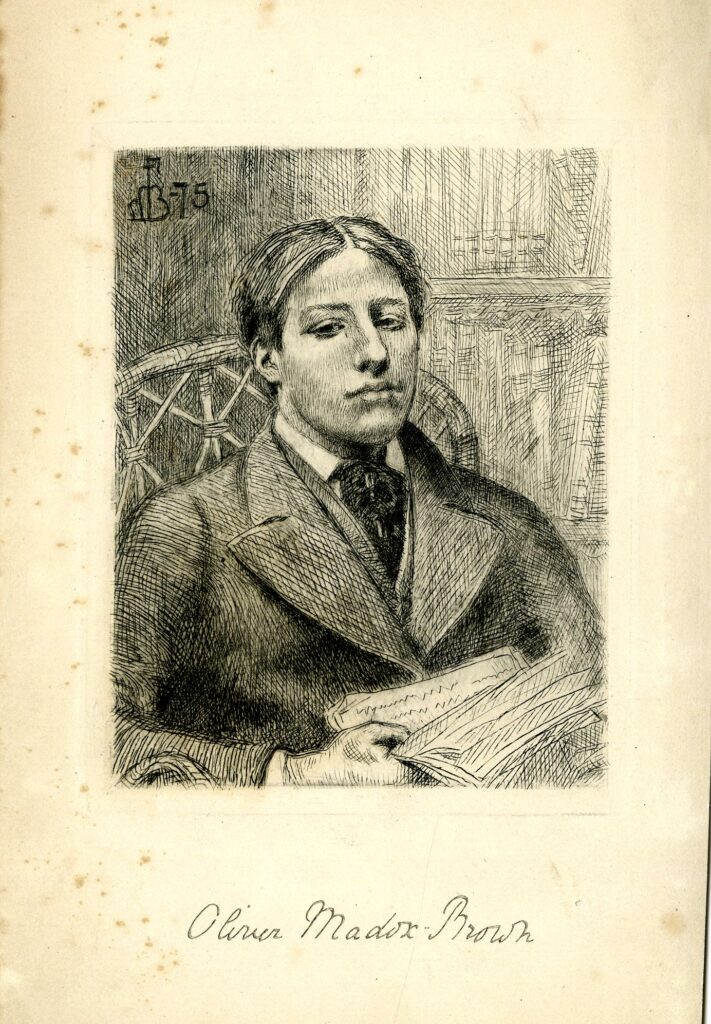

In Conway’s description of the funeral of Oliver Madox Brown, who died from blood poisoning in 1874 at just 19, the deeply humanist impulses of the bereaved father are given clear expression, and offer an insight into the shared beliefs of Brown, his son, and Conway.

Ford Madox Brown, in his letter requesting my services at the funeral, expressed to me his disbelief of all theologies. But although without any of these hopes of future life in which believers find consolation, I never knew in all my ministry, whether among Methodists or Unitarians, more courage than was displayed by this devoted father under unexpected and terrible affliction. Stricken as by a thunderbolt, he was yet not shattered. He set himself to soothe the bereaved ones around him; he sustained them on his great heart; and he never faltered in devotion to his art.

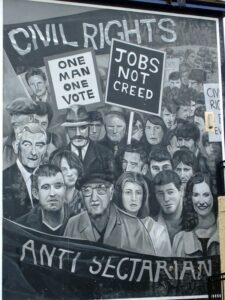

A concern for others was a marked feature of Ford Madox Brown and his wife, Emma. During the winter of 1860, the couple opened a soup kitchen, and during the latter years of his life in Manchester, Brown created a labour bureau in an effort to support the unemployed. Inspired by his own sympathy with the sufferings of others, and by the artist William Hogarth, Brown sought to include a sense of social realism in his artworks. He proposed, for example, to depict the Peterloo Massacre among the series of historical murals he was commissioned to produce for Manchester Town Hall in 1878. The Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819, during which 18 were killed and nearly 700 injured, had followed peaceful protests for increased voting rights and the relief of poverty. One of Brown’s best known paintings, Work, has been described by Tim Barringer as the ‘most complex and sophisticated British modern-life painting of the nineteenth century’.

Ford Madox Brown died on 6 October 1893, and was buried in St Pancras and Islington Cemetery, with a non-religious ceremony conducted by Moncure Conway. Among the attendees were many notable freethinkers, including poet Mathilde Blind, artist Walter Crane, and writer William Michael Rossetti.

During a long life he received little honour, and few honours, and was in some ways a singularly unlucky man. But he managed to work on, to do good work, and, as he quaintly phrased it, ‘to go to bed with both ears on.’

Ford Madox Ford (Brown’s grandson) in Ford Madox Brown: A Record of his Life and Work (1896)

Although, as The Times noted, underappreciated in his own lifetime, recent critical opinion has placed Ford Madox Brown firmly among the most important of 19th century British artists. Recollections of Brown testify to his profound humanism, depicting a lifelong freethinker, a good friend, and an unstinting creative. Brown’s humanist and artistic legacy was continued through his daughter, Lucy Madox Brown, who in 1874 married William Michael Rossetti, another eloquent agnostic. The couple shared radical politics and a humanist outlook, as well as prodigious artistic talent.

Ford Madox Brown | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Works by Ford Madox Brown | Manchester Art Gallery

The Life and Letters of Frederic Shields by Ernestine Mills

Ford Madox Brown: A Record of his Life and Work by Ford Madox Ford

Main image: Self-Portrait by Ford Madox Brown, 1877. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop

We desire to attract men and women holding all shades of opinion, but having in common a conviction that morality […]

There is no one who will deny the value and importance of truth, but how is it to be ascertained, […]

A brief history of humanism and secularism in Northern Ireland Organised humanism began in Northern Ireland in the 19th century, […]

There are in Britain today a great many thoughtful people who have ideals and aspirations that owe nothing to religious […]