Our goal must be the good of the whole human society.

Henry Noel Brailsford, Olives of Endless Age: being a study of this distracted world and its need of unity (1928)

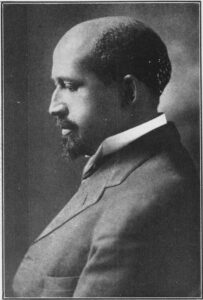

Henry Brailsford was a progressive journalist and author, and a dedicated campaigner for international cooperation and human rights. He published numerous books on international relations, peace, and socialism, and also two highly-regarded works for the Home University Library: Shelley, Godwin and Their Circle, and Voltaire. Kingsley Martin, his employer for nearly two decades at the New Statesman, described him as ‘the finest British journalist of his time’. Martin and Brailsford were both prominent humanists as well as prolific writers, and Brailsford served as President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK) 1945-6.

Happiness, indeed, in Aristotle’s language, is “the exercise of our vital faculties in accordance with virtue”.

Henry Noel Brailsford, Socialism for To-day (1925)

Henry Brailsford was born at Mirfield, Yorkshire in 1873, the son of a clergyman, and was educated at Dundee High School and at the University of Glasgow where he taught for a year before becoming a journalist. While still young Brailsford reacted strongly against what he saw as his father’s authoritarianism, hypocrisy and selfishness. A school essay entitled: ‘Is there a God?’ caused a minor scandal, and once at University Brailsford replaced his father’s Methodism with a conviction that human and social progress must be sought in the present world.

Brailsford’s compassion and humanitarianism caused him to identify with the plight of small nations and with oppressed people everywhere. In 1897 this idealism led him to volunteer with the Philhellenic Legion to help defend Greece against a Turkish invasion. Brailsford was wounded during the fighting retreat from Driskoli, an experience which left him with a deep distrust of jingoism and a hatred of the brutalities of war. Further valuable international experience was acquired doing relief work in Crete and Macedonia with his wife Jane Malloch.

As a young journalist Brailsford was mentored by the formidable Manchester Guardian editor C.P. Snow who gave him assignments in Crete and Greece before sending him to Paris to cover the Dreyfus affair, but Brailsford turned down a permanent position on the paper and worked instead for a succession of progressive and left-wing publications. Driven by his strong sense of justice, Brailsford used his platform as a journalist to speak out against oppression in Albania, Armenia, Ireland, Macedonia and Russia, and he exposed both child labour in Egypt and slave labour in Angola.

A founding member with Laurence Housman and others of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage, Brailsford resigned his position as principal leader-writer on the Daily News in protest at the paper’s failure to condemn the government’s force-feeding of suffragette hunger-strikers. He then devised a plan to bring about women’s suffrage legislation through all-party talks, but his initiative broke down due to the mutual distrust between the suffragette leaders and the government.

In 1922 Brailsford became editor of the Independent Labour Party’s paper New Leader and made it a journal of literary excellence, covering both politics and the arts. In the field of foreign affairs Brailsford’s editorials argued for an ethical foreign policy, international cooperation and arms limitation. He was active in both the Union of Democratic Control and the League of Nations Society, and advocated for a federal Europe as a way of guaranteeing peace. His opposition to war was both ethical and humanitarian:

War is the suspense and annihilation of the individual conscience. It blots out for the soldier the humanity of the men whom he opposes, and blurs them together in one unrealised and unimagined horde which he calls the enemy.

Brailsford was an active supporter of the World Union of Freethinkers, and became an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association in 1943. In 1945, he was made President of the Ethical Union.

H.N. Brailsford died on 23 March 1958. A Times obituarist described Brailsford’s ‘reasoned and rationalist left-wing inspiration’, his ‘warm humanity and clear brain’. Throughout his life Brailsford had an unswerving devotion to liberty, democracy and religious toleration, and felt a strong affinity with the seventeenth-century English Radicals. His book The Levellers and the English Revolution was published after his death.

A humanist and humanitarian, Brailsford devoted his life to championing compassion and cooperation. Alongside other activists of his generation, notably Bertrand Russell, Laurence Housman, and Fenner Brockway, his efforts for equality and international understanding were braced by a firmly held humanism. Brailsford’s summary of Voltaire’s life could perhaps be taken as his own epitaph:

He sought above all else to erect for society a new scheme of values among the goods that men desire. He found it in the exaltation of constructive work for the common good. He smashed the barriers of nationality and creed, that in this effort separate mankind. He saw, across wars and schisms, the great cosmopolitan society. He preached, as the one sufficient commandment, the love of one’s fellowmen, and made it concrete and vital, by his relentless assaults upon every sort of cruelty.

Henry Noel Brailsford, Voltaire (1935)

The Last Dissenter: H.N. Brailsford and his World by F.M. Leventhal (1985)

Henry Noel Brailsford | Spartacus Educational

By Paul Ewans

About the moral problem there is nothing mysterious; it is simply the old, old question of how best to live […]

If living does not give value, wisdom and meaning to life, then there is no sense in living at all. […]

… in broad terms, with our lecturers we attempt to define our intellectual standpoint; with our music we try to […]

Positivism is a philosophical system based on the writings of French thinker Auguste Comte, which flourished from the 1830s onwards. […]