I don’t believe in God, but I think morality is fundamental to human life.

Iris Murdoch in the Literary Review, April 1983

An obituary first published in New Humanist, March 1999.

Iris Murdoch, one of the leading British novelists of the second half of the twentieth century, has died aged 79. She was prolific and playful, yet enormously serious. She was not quite a humanist, but explored ideas of great interest to humanists. As a philosopher and a novelist, she concocted a literary amalgam which brought ideas into the English novel, while sustaining a strong sense of the quiddity, the muddle of human life.

As a philosopher and a novelist, she concocted a literary amalgam which brought ideas into the English novel, while sustaining a strong sense of the quiddity, the muddle of human life.

She was born in Dublin and, though brought up in London, retained a sense of her Irishness. She was educated at the progressive Badminton School, Bristol. She gained a first in Greats at Oxford, where she became fascinated by philosophy.

From 1942-44 she worked at the Treasury and from 1944-46 for the United Nations Rehabilitation and Relief Association in Brussels and Austria. Exiles of various types constantly pop up in her novels. She met Sartre and was at first very excited by existentialism, but she became increasingly critical of his notion of ‘the person’ as was apparent in her first published book: Sartre: Romantic Rationalist (1953). She was by now teaching philosophy at St Anne’s College, Oxford, where she was a tutor and fellow for 15 years. Despite becoming primarily a novelist, she continued to write philosophical essays, dialogues and books. Her latest and largest philosophical work was Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (1992) in which she explored the relationship between morals and religion. The philosophical ideas and the ideas within the novels can be seen to be related, but it is not necessary to be a student of philosophy to understand the novels.

Flight from the Enchanter (1956) encapsulates one of her main themes – how love enchants and deludes us, so that we cannot see clearly the reality of the loved one. The struggle to see one another clearly, becomes in Murdoch’s novels a moral duty.

Under the Net (1954) was a brilliant novelistic debut. Although she was always perhaps a more humorous novelist than commentators allowed, the comedy of her first novel was combined with a taut plot and a coruscating argument with some of Sartre’s ideas. Flight from the Enchanter (1956) encapsulates one of her main themes – how love enchants and deludes us, so that we cannot see clearly the reality of the loved one. The struggle to see one another clearly, becomes in Murdoch’s novels a moral duty. It seems, however, that her characters too often fail to emerge from the fantasy that enmeshes them. The Bell is one of her most realistic novels, with an Anglican community falling apart, from the diverse love which should hold it together.

Her best novels were from her middle period. The Black Prince (1973) and The Sea, the Sea (1978) were tragicomedies in which characters were caught in the amorous roundabout and intellectual whirligig. The later novels became baggy, but could retain the readers’ interest. It is an irony that a novelist so seriously concerned to represent the reality of life, gathers a cast list of people so unlike those we meet in our daily life. But like Dickens or Dostoevsky, she created her own world – ‘Murdochian’ is a recognisable literary adjective.

Iris Murdoch was not quite a humanist. She did not believe in God, but she did feel some value in the ‘sacred’.

Iris Murdoch was not quite a humanist. She did not believe in God, but she did feel some value in the ‘sacred’. She sometimes described herself as a Christian Buddhist. In a television interview, reprinted in the New Humanist (Winter 1985), she declared that there ‘is something in common between Buddhism and Christianity… that is the task of people in this world to become good, to love unselfishly, to overcome egoism.’ In the same interview she spoke of the unconscious mind: ‘the ‘extraordinary deep reservoirs of imagery and thought and force: great power, darkness and terror which are in the mind and soul and sometimes you get a kind of energy which comes from this region, some unexpected enlightenment or vision.’ Were her ‘evil’ characters more mischievous than demonic? were her good characters too self-righteous? Humanists can be concerned with the search for goodness and the power of nightmares.

In her last few years. Iris Murdoch suffered, tragically, from Alzheimer’s disease. Amazingly in one of her early novels – The Bell – Iris Murdoch wrote of one of her characters with a capacity to forget: ‘That she had no memory made her generous’. Her husband, John Bayley’s account of her illness (Iris: A Memoir o f Iris Murdoch, 1998) suggests that she too was generous while suffering loss of memory. What cannot be lost is the extraordinary generousness of her output as a novelist.

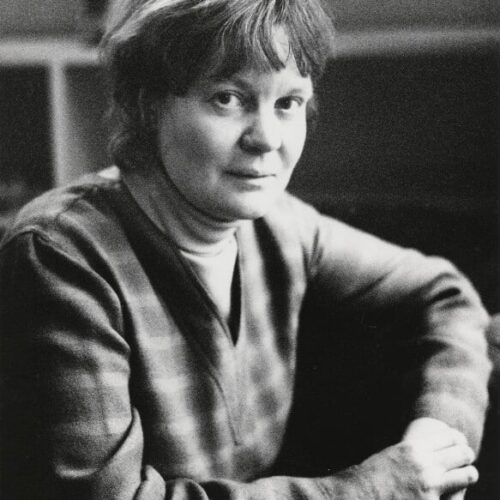

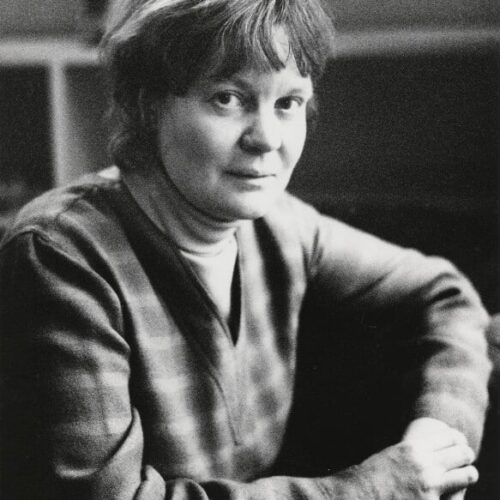

Main image: Iris Murdoch by Godfrey Argent, bromide print, 10 December 1969 NPG x87793© National Portrait Gallery, London

Faith without works is not Christianity, and unbelief without any effort to help shoulder the consequences for mankind is not […]

In the first place, then, why do we botanise?… The enjoyment of the beauty and fascination of flowers in their natural […]

The gist of heresy is free personal choice in act, and specially in thought – the rejection of traditional faiths […]

Harriet Martineau described her escape to atheism like this: “I lingered long on the stages of speculation and taste, but […]