Rationalism is… primarily a mental attitude, not a creed or a definite body of negative conclusions. No uniformity of opinions must be sought in the thousands of men and women of cultural distinction who are here included in a common category.

Joseph McCabe, preface to A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Rationalists (1920)

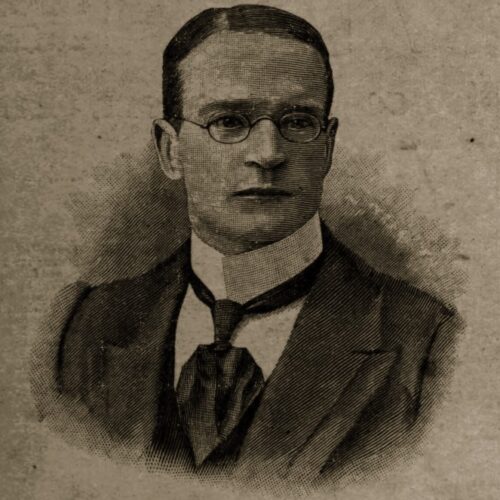

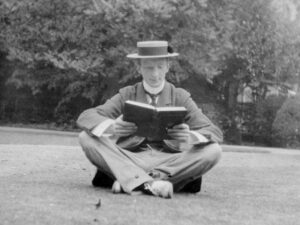

Joseph McCabe was a prolific writer and freethinker, who went from Catholic clergyman to ‘trained athlete of disbelief’. As a leading light of the Rationalist Press Association, Vice President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), and an appointed lecturer at South Place Ethical Society (Conway Hall) for almost 50 years, McCabe’s influence spanned the rationalist and humanist movement.

The predominant feeling of our troubled age is social and humanitarian. We want to understand human life: to learn its meaning, its laws, its destiny.

Joseph McCabe, The Evolution of Civilization (1921)

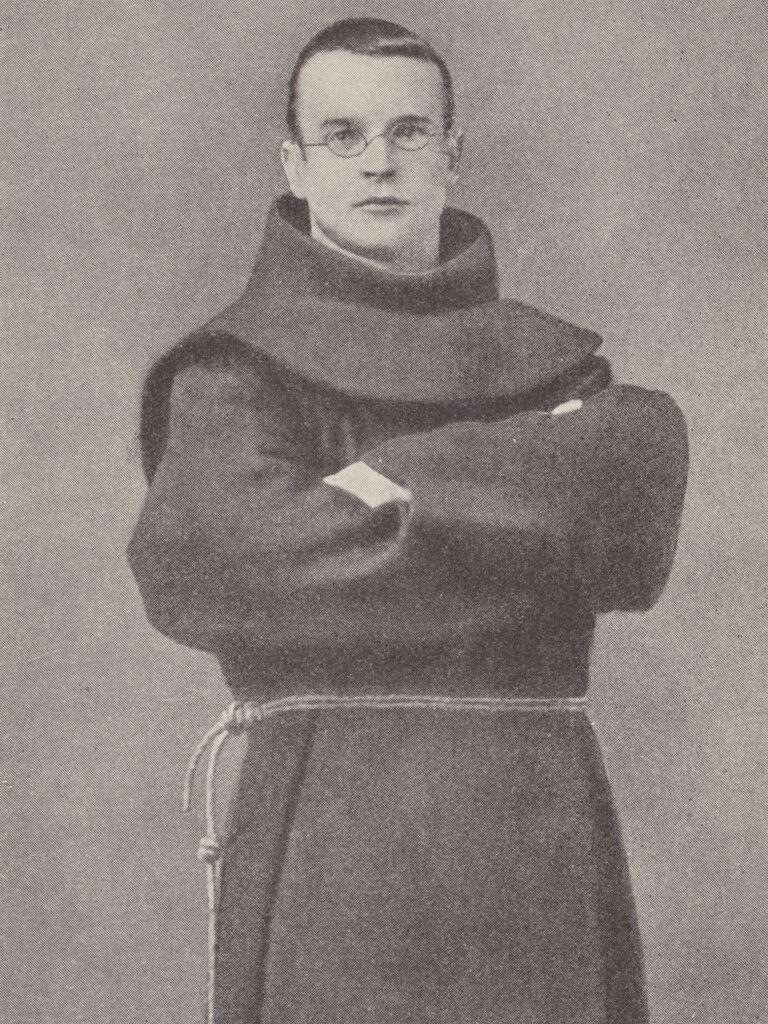

One of the most prolific polymaths of the 20th century, Joseph Martin McCabe was born in Macclesfield, Cheshire in November 1867 into a family of modest means. As the second-born from a Catholic family, Joseph was earmarked for the priesthood, which he began the preparation for aged 16. He was soon the victim of sexual abuse, about which he remained silent until he was 74 years of age and which troubled his personal and work relationships for his entire life. Understandably, from early in his church career, McCabe suffered doubts about his vocation. Father Antony, as he became, rallied repeatedly, expelled his doubts, and rose through the ranks. His priestly vows prohibited him accepting the doctorate his study at Louvain University would otherwise have qualified him for. Aged only 23 he was appointed Professor of Philosophy and Ecclesiastical History at a seminary in London in 1890. But from 1893 onwards, Father Antony’s doubts became, in his words, dark and permanent, and he spiralled into a crisis of faith at the end of 1895. On Ash Wednesday 1896 he left the Church to begin a new life in the wide world, completely untutored in its ways.

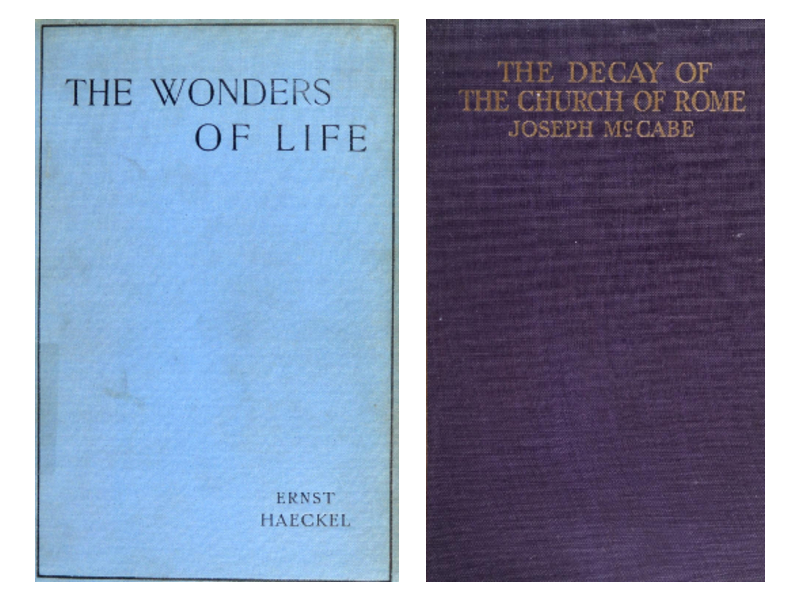

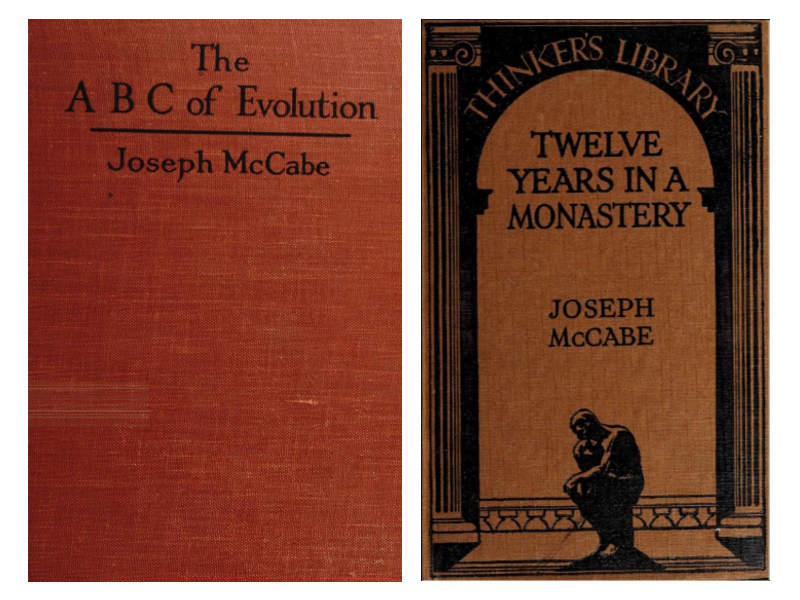

McCabe soon found a new life in London, becoming associated with the fledgling Rationalist Press Association and Watts & Co., its publishing arm. For more than half a century McCabe made his living from his pen, writing an extraordinary range of books, monographs, pamphlets, magazine and newspaper articles, encyclopaedia entries and, indeed, entire encyclopaedias. It was McCabe who translated Ernst Haeckel’s evolutionary blockbuster The Riddle of the Universe, which appeared in English in 1900 and remained one of Watts & Co.’s biggest sellers. By 1914, a Christian opponent described him as the RPA’s ‘leading spirit’. Over his career, McCabe wrote at least 95 books, 104 monographs, and 138 pamphlets. When not writing, McCabe gave more than 4000 lectures to audiences around the world and took part in at least a dozen major debates, the most notable of them on spiritualism with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in 1920. The research McCabe undertook for that debate alone generated two books. H. G. Wells spoke of McCabe as the ‘trained athlete of disbelief’.

More than anything else, it was evolution that tore away the fabric of his religious belief. Over half a century he wrote ten works on evolution, the best of them being The Story of Evolution (1912) and its successor The New Science and the Story of Evolution (1931). He was more able than many of his contemporaries to distinguish a genuine intellectual development from a passing fad. He was, for example, sceptical of social Darwinism, which he denounced in 1914 as a ‘pseudo-scientific application of evolutionary views to social problems’. And eugenics was dismissed, very perceptively, as ‘secular Calvinism’. On most occasions when he departed from the conventional wisdom of the time, it was to assert a strictly Darwinian reading of the issue at hand. Events have largely proved him correct. Neither was McCabe guilty of scientism, or placing faith in science as an agency of salvation. He made the simple observation that we ‘do not want to substitute the word science for the word God.’

McCabe’s other great interest was the Catholic Church, about which he wrote as much as an original scholar as he did as a populariser. Being fluent in Latin, Greek, French, German, Spanish and Italian, he could use original documents not available to others. Crises in the History of the Papacy (1916) remains a worthwhile historical study. Even his later works, like A History of the Popes (1939), while more combative, still confined his criticisms to the Vatican and prominent Catholic apologists and avoided the sweeping criticisms of Catholics as people. McCabe also wrote two autobiographical studies of living in the church, in particular Twelve Years in a Monastery (1897) which told of fellow priests driven mad by sexual frustration, ruined by drink, or sunk into triviality as the only means of surviving the unnatural regime they found themselves in. His autobiographical works avoided the tabloid sensationalism that so many others writing this sort of work indulged in. H. G. Wells and James Joyce were among the many people who acknowledged McCabe’s influence on their views about the Catholic Church. Only very late in his life did one or two of his minor works cross the line into polemic. For the vast majority of his career, McCabe was a principled anti-clerical, making criticisms now accepted even by Catholic scholars about papal politics and corruption.

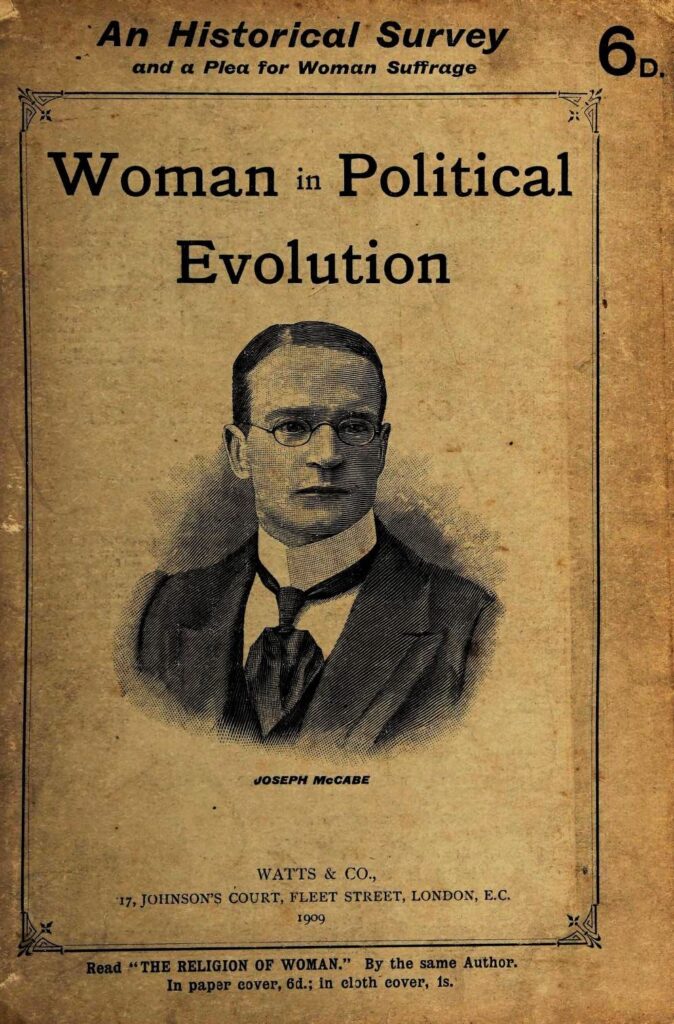

McCabe was also an early feminist, describing himself as such. He campaigned actively for the women’s suffrage movement, although he did not support the move toward more militant forms of protest after 1911. His two books on the status of women, The Religion of Woman (1905) and Woman in Political Evolution (1909) avoided the patronising tone of many male suffrage supporters. But it is probably his later work Key to Love and Sex (1928) that is the most remarkable. This eight-volume study, written for Haldeman-Julius, was a no-frills users-guide to modern thinking about sex and gender. He frequently criticised males who advocated female liberation merely so that they could have a freer access to problem-free sex and refuted prejudices about women being more emotional and more religious than men. He even devoted time to defending blondes from the usual accusations. McCabe wrote widely in other areas, including some well received biographies of St. Augustine, Abelard, Goethe, Talleyrand, Cardinal Richelieu, and George Bernard Shaw. He also wrote two novels; In the Shadow of the Cloister (1908, under the pseudonym of Arnold Wright) and The Pope’s Favourite (1917). Even where he was wrong, McCabe set a good example. For instance, he defended the notion of ether far longer than was seemly, which made it difficult for him to accept Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. But when, by the mid-1920s, he did finally accept he was wrong, he launched into explaining the Theory of Relativity to his readers.

With few close friends among his contemporaries, McCabe never came to terms with the fact that people leave religion for different reasons, and found it difficult to accept that others, whose path to freethought had been less fraught, were equally sincere. He broke with the RPA in 1928, although a partial rapprochement was effected in 1934. Most of his later works were published by Emmanuel Haldeman-Julius in the United States though his Rationalist Encyclopaedia (1948) was published by Watts & Co. in England. McCabe died on 10 January 1955, aged 87. He expressed the wish (unfulfilled) to have as his epitaph, ‘He was a rebel to his last breath’.

Joseph McCabe was a gifted and responsible populariser of contemporary thinking to non-specialist readers. He was unfazed by intellectual fashions, being ready to identify himself as an atheist, materialist, and feminist, long before these terms were academically respectable. He avoided most of the errors of his day and gave his readers accessible and reliable overviews on a wide variety of subjects. Joseph McCabe deserves to be linked with Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan as among the most acute and lucid popularisers of the 20th century.

A Rebel to His Last Breath: Joseph McCabe and Rationalism by Bill Cooke (2001)

Works by Joseph McCabe | Internet Archive

By Bill Cooke

I cling to my tiny philosophy: to hug the present moment. Virginia Woolf, diary entry, 31 January 1940 Virginia Woolf […]

No one who came in contact with her failed to recognize in her fearlessness, honesty for the sake of honesty […]

Founded in 1263, Balliol College is one of the oldest colleges at the University of Oxford. Established by the English […]

They weren’t just trying to sell something to parents, they were helping them to understand how to play with and […]