I believe in the supreme virtue of exploring. I believe in finding out. Even if I don’t succeed, I still believe in the value of the search. The goal is better human relationships and more human happiness.

Kingsley Martin, ‘This I Believe’ for the BBC, 19 March 1953

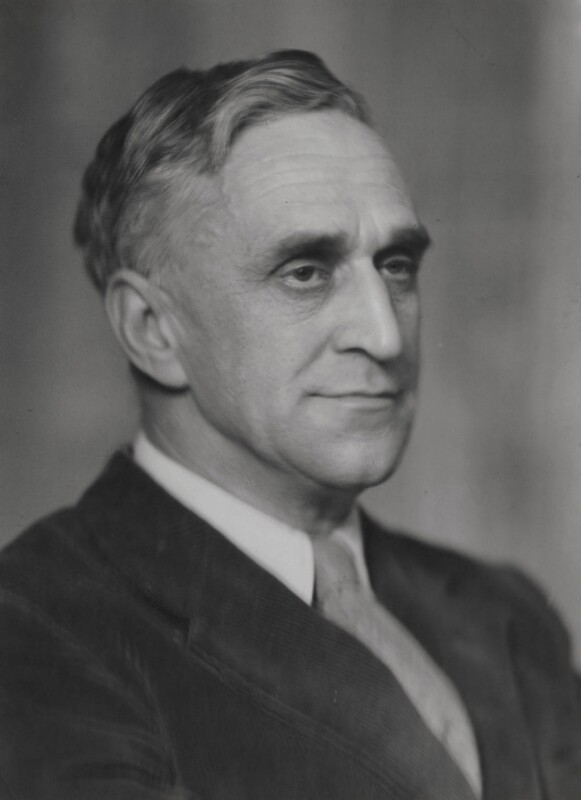

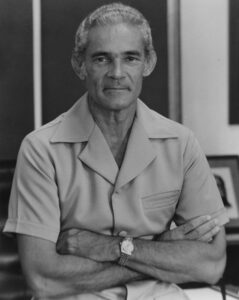

Kingsley Martin was the decades-long editor of the New Statesman, a co-founder of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, and a prominent, principled humanist. A journalist, writer, and activist, Martin was a contributor to The Humanist Outlook (1968), in which he stated his long standing belief that ‘God was merely a word we used to explain anything we didn’t understand.’ He was an early member of the Cambridge Heretics, an Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, and a member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK).

What I take Humanism to be is an effort to feed humanity, with all its emotions and built-in search for righteousness, as well as reason, into our personal computer.

Kingsley Martin, ‘Rock of Ages’ in The Humanist Outlook (1968)

Basil Kingsley Martin was born in Hereford on 28 July 1897, the son of a Congregational minister. Of his father, whose socialism and pacifism Martin inherited, he wrote:

My trouble was that my father gave me no chance at all to quarrel with him. If he had been a dogmatic Christian, I should have reached my later humanism long before I did. If he had been an atheist I might have relapsed into some form of Christian faith. But he was ready to discuss everything and to yield when he was wrong… I fought side by side with him, and was a dissenter, not against his dissent, but with him against the Establishment. His causes became my causes, his revolt was mine.

Father figures: The Evolution of an Editor, 1897-1931 (1966)

While still attending school, Martin appeared before a conscientious objectors’ tribunal, subsequently serving with the Friends’ Ambulance Unit in France 1917-18. The following year, he went up to Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he excelled. Martin’s first employment was as an assistant lecturer at the London School of Economics (LSE), under fellow humanist Harold Laski, of whom he would later write a biographical memoir. For three years from 1927, Martin was a writer for the Manchester Guardian. In 1931, he was appointed editor of the New Statesman, the role in which he made his name. He remained at its helm for 29 years.

Under Martin’s editorship, the New Statesman’s circulation grew sixfold. It was a critical and commercial success, and the paper acted – in the words of Frank Hardie – as ‘a kind of Bible’ for the left. Martin articulated a desire for progress and a quest for truth which was evident too in his firmly held humanism, about which far less has been written. He was, though, a contributor to both Objections to Humanism (1963) and The Humanist Outlook (1968), writing in the former:

We have good reason to believe in the possibility of far greater happiness if society pays attention to ethical principles that follow from the needs of our common humanity. Humanism is an attitude of mind… It becomes a duty, not only a sensible line of conduct, to work for a world society and dedicate our lives to the still rational hope of progress. The future depends on ourselves, not on any doctrine.

Kingsley Martin, ‘Is Humanism Utopian?’ in Objections to Humanism (1963)

In the same year, Martin attended the inauguration of the umbrella British Humanist Association at the House of Commons, toasting this collaboration between the Rationalist Press Association and the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK), with which he would remain actively involved.

In Objections to Humanism, Martin made the case for acknowledging – and acting upon – the humanist values which had become the common sense of so many. He argued that a majority of people had already rejected revealed religion ‘except in some symbolic sense’, and failing to act accordingly risked a hypocritical society and the stifling of progress. ‘The pretence of believing mythology’, he suggested, ‘makes it difficult to face public issues realistically’. Instead, Martin argued, our responsibility was the here and now:

No longer will the prospect of immortality compensate for the miseries of this world. Many will deplore the loss of faith in immortality… All that we can say is that life here can be happier for our children and our successors if we learn and practise the laws of well-being.

Although Martin acknowledged the pull of religion, both for comfort and community, he believed the duty of humanists was to demonstrate ‘that our problems can be dealt with rationally and that progress is still possible’. He also refuted the idea that morality was synonymous with religion, writing:

I do not believe that morality depends on belief in any set of theological doctrines; it is statistically true that people do not behave better because they hold long-established doctrines… the morality accepted in any society does not depend on the Churches… but on the basic needs of a civilized society. The reason for talking about the fatherhood of God is the social necessity of the brotherhood of man.

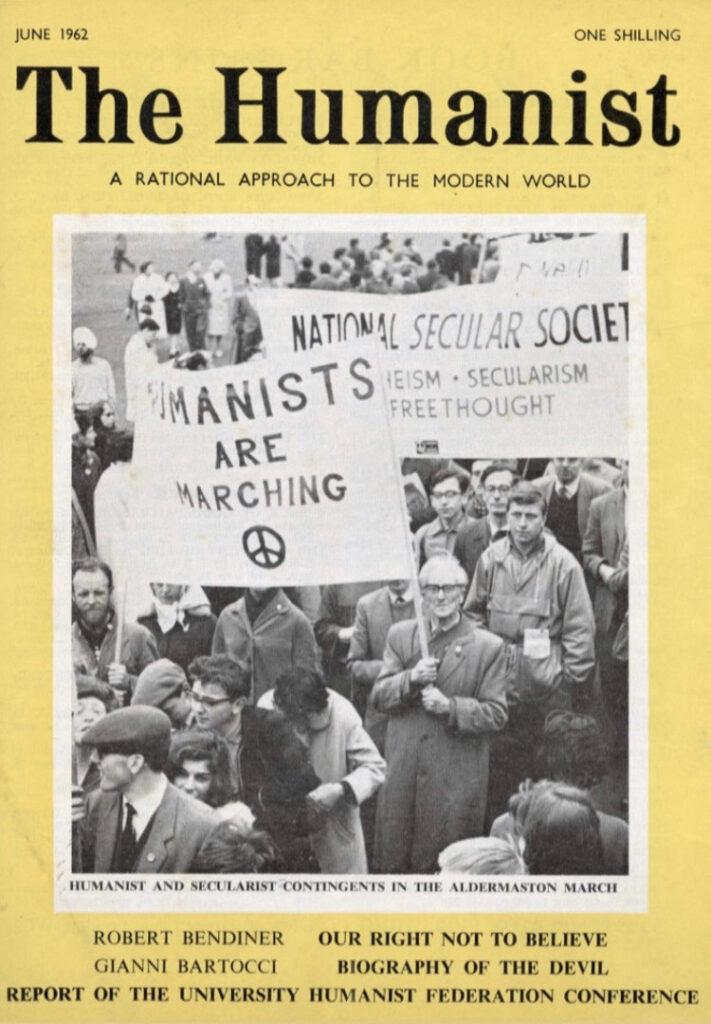

Martin’s own belief in the brotherhood of man found expression in his lifelong commitment to socialism, and his co-founding of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the 1950s. The CND drew the active support of scores of other humanists, among them Bertrand and Dora Russell, Fenner Brockway, Peter Ritchie Calder, Benjamin Britten, E.M. Forster, Julian Huxley, Doris Lessing, Miles Malleson, and Barbara Wootton. As Hector Hawton would later write, ‘that vision of the Good Society which has haunted the best minds through the ages was the lure that inspired his political faith’.

Dorothy Woodman, Martin’s partner for the final decades of his life, wrote that in his last years he faced progressive illness and the fact of death with ‘great courage, [and] great common sense,’ remarking: ‘how true to his humanism’. Kingsley Martin died in Cairo on 16 February 1969. He left £100 to the British Humanist Association in his will, and donated his body for medical research. A note in the BHA’s annual report said: ‘We shall remember his life with gratitude, proud of his association with us.’

If we recall the names of those we all revere as deserving mankind’s greatest praise, we do not find that most of them have been believers. Mainly they have been those who have deepened and broadened knowledge, or increased happiness through their understanding of the present world… The concern of thinking people is with the health, wealth and happiness of mankind. Our job is the well-being of men and the hoped-for peace among nations.

Kingsley Martin, ‘Is Humanism Utopian?’ in Objections to Humanism (1963)

On his death, Humanist News (the journal of the British Humanist Association, now Humanists UK), was quick to point out that although ‘omitted in nearly every other obituary’: ‘Kingsley Martin was through and through a Humanist and a life-long champion of Humanist causes’. In the pages of The Humanist, Hector Hawton described Martin as a man who ‘wanted passionately to bring more of the good things in life within the reach of more and more people.’ His biographer, C.H. Rolph, suggested that Martin would have used his third autobiographical volume to explore in depth his humanism and ethics, but even without this, Kingsley Martin’s legacy as a thinker, activist, and humanist is secured by his writings and his role in bringing about the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Like Bertrand Russell and E.M. Forster before him, Martin also gave eloquent expression to those humanist values which underpinned his life and work.

I believe in the supreme virtue of exploring. I believe in finding out. Even if I don’t succeed, I still believe in the value of the search. The goal is better human relationships and more human happiness. Pursuing this adventure, I find myself in a goodly company of men and women both alive and dead; our friendships are cemented by failure and frustration, but our search is now and again rewarded by the occasional creation of some new beauty of form or the perception of some new aspect of truth. One hears it go “click” like the latch of a door when one finds the right key. It is this click of friendship, of knowledge, and of art in which I believe.

Kingsley Martin, ‘This I Believe’ for the BBC, 19 March 1953

Kingsley Martin | Modernist Archives

Kingsley Martin, Father figures: The Evolution of an Editor, 1897-1931 (1966)

Kingsley Martin, Kingsley Martin: Portrait and Self-portrait (1969)

C.H. Rolph, Kingsley: the life, letters and diaries of Kingsley Martin (1973)

Kingsley Martin | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Not by the Creed but by the Deed. Motto of the Society for Ethical Culture of New York, founded in […]

No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, […]

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

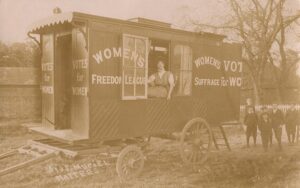

Dare to be free. Slogan of the Women’s Freedom League The Women’s Freedom League (WFL) was a militant suffrage organisation, […]