There is nothing in this world to compare with the joy of finding something to do that one believes to be absolutely worth while, and doing it.

The Viscountess Rhondda, This Was My World (1933)

Lady Margaret Rhondda was a prominent businesswoman, suffragist, magazine proprietor, and philanthropist whose humanism was manifested primarily in her lifelong support for women’s rights. As a leading member of the women’s movement during the inter-war period, she made a significant contribution to the creation of a more just and equal society. In her autobiographical writings, Lady Rhondda wrote in detail about her loss of religious faith while still a teenager. Thus, her lifetime of activism for equality was rooted firmly in a sense of goodness for its own sake, and the incomparable joy of – in her own words – ‘finding something to do that one believes to be absolutely worth while, and doing it’.

I doubt, I very much doubt, whether if I had been born say twenty years earlier, or had a less understanding family or less amazingly modern-minded father, I should ever have done anything outside the home at all… I know that I should have been unhappy, but I doubt if I should have known why I was unhappy… I should merely have lived uncomfortably—uncomfortably for myself and notably uncomfortably for other people.

The Viscountess Rhondda, This Was My World (1933)

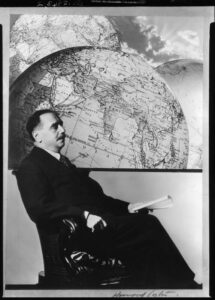

Margaret Haig Thomas was born in Bayswater, London, the only child of suffragette Sybil Haig and Welsh businessman David Alfred Thomas MP. Educated at Notting Hill High School for Girls and St Leonards School in St Andrews, it was in her late teens Margaret concluded that ‘none of the Bible was likely to be true, and that it was probable that there was no hereafter.’ The process of arriving at these conclusions, she wrote, was an ‘exceedingly painful’ one, which led her largely to keep her thoughts on religion to herself, afraid of initiating the same pain in others. Upon leaving school she ‘came out’ as a debutante and endured three London ‘seasons’ before escaping to Somerville College, Oxford. She left Somerville in her first year and returned to her family home in Llanwern, Wales. In 1908, she married Humphrey Mackworth, a nearby landowner and hunting man. They divorced, amicably, in 1923.

In 1908 Margaret Mackworth joined the suffragette Women’s Social and Political Union to campaign for the vote, becoming Secretary of the WSPU’s Newport branch. Having embraced the cause almost instinctively, she educated herself by extensive reading of feminist literature and then, hoping to inspire her branch to greater militancy, set fire to a letter box. She was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison, but was released after five days on hunger strike. In her memoir, This Was My World, Mackworth described militant suffrage as ‘the very salt of life’:

The knowledge of it had come like a draught of fresh air into our padded, stifled lives. It gave us release of energy, it gave us that sense of being some use in the scheme of things, without which no human being can live at peace.

In 1915 both Mackworth and her father survived the sinking of the Lusitania by a German submarine. Thomas then took his daughter into his business as his ‘right-hand man’ and on his death in 1918 she inherited the whole concern. She also inherited her father’s title, becoming the Viscountess Rhondda. By the following year Rhondda was sitting on the boards of 33 companies and was chairing seven of them. She later became the first woman President of the Institute of Directors.

During the First World War Rhondda was employed by the government to encourage women to take up war work and after the war she used her new-found expertise to promote women’s employment more widely. She launched the Women’s Industrial League to open up the trades and professions to women, and created the Open Door Council to campaign against the restrictive legislation which prevented women from taking well-paid jobs in mining and other industries.

Having succeeded to the peerage on her father’s death, Rhondda petitioned to take her seat in the House of Lords. The Committee for Privileges voted to issue the necessary writ, but the Lord Chancellor engineered a reversal of this decision. Rhondda was outraged and never ceased to campaign on the issue. But it was not until 1963 that peeresses could sit in the Lords in their own right.

In 1920 Rhondda founded Time and Tide, a weekly feminist journal entirely controlled, edited, and staffed by women. Her aim was to promote women’s rights by reaching the ‘keystone people’ who influenced ideas across society. The journal thus presented a wide range of views while maintaining a strongly feminist editorial line. Rhondda published work by an impressive list of writers including Vera Brittain, T.S. Eliot, Winifred Holtby, D.H. Lawrence, Katherine Mansfield, George Bernard Shaw and Virginia Woolf. In the lead up to and throughout the Second World War, Time and Tide took a firmly anti-fascist stance, earning Lady Rhondda a place on the Nazi blacklist. Rhondda continued to edit and subsidise the journal for the rest of her life.

There is another need in our press of which the average person of today is conscious, but which must specially weigh with women – the lack of a paper which shall treat men and women as equally part of the great human family, working side by side ultimately for the same great objects by ways equally valuable, equally interesting; a paper which is in fact concerned neither specially with men nor specially with women, but with human beings.

The Viscountess Rhondda, This Was My World (1933)

In 1921 Rhondda created the Six Point Group to advance women’s interests in specified areas, notably the rights of mothers, widows’ pensions, equal pay for women teachers, and equal opportunities in the civil service. Rhondda also continued to campaign for women to get the vote at the age of 21 (the Representation of the People Act 1918 having given the vote only to women over 30 who met a property qualification). Her Equal Political Rights Committee organised a mass demonstration in Hyde Park to remind the government of the militant methods used by the suffragettes, and this approach succeeded when the Equal Franchise Act 1928 finally gave women the vote on the same terms as men.

In 1940, in a contribution to the edited collection This I Believe, Rhondda wrote of having ‘turned back to the Christian faith’. This was based, she wrote, on a rejection of the idea ‘that there was nothing in the whole universe beyond what we ourselves with our five senses could touch, taste or handle’. Interestingly, though, she quoted humanist professor Gilbert Murray in discussing the great mystery she saw in the world. Regardless of whether Rhondda moved back towards religion during her later years, at the heart of her philosophy remained the ideal of freedom for all, which had animated her decades of activism.

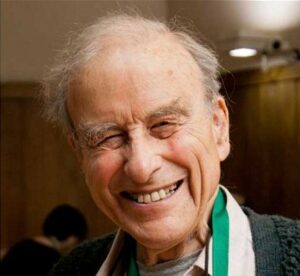

Lady Rhondda remained active for as long as she could, even refusing treatment for cancer in order to stay working on Time and Tide. She died in Westminster Hospital, London on 20 July 1958. Her ashes were buried at Llanwern.

Lady Margaret Rhondda was one of the most important and influential feminists of the early 20th century. She was deeply concerned that all women should have the opportunity to live full and satisfying lives, and was convinced that ending discrimination against women would produce a more humane and peaceful society. Her uncompromising commitment to women’s rights helped to change public attitudes and brought tangible progress towards equality between the sexes. Although her humanism is often overlooked in biographies, Lady Rhondda’s struggle with, and loss of, religious faith in her late teens helped to shape her commitment to rational and practical action. Like a remarkable number of her fellow campaigners, her subsequent activism was rooted in an acute sense of justice, and a striving towards happiness in this life for herself and others. She remained committed to thinking for herself and working for equality for everyone, using her own privilege and labour to seek greater opportunities for all.

The Viscountess Rhondda, This Was My World (1933)

Angela John, Turning The Tide: The Life of Lady Rhondda (2014)

Catherine Clay, Time and Tide: The Feminist and Cultural Politics of a Modern Magazine (2018)

Lady Rhondda | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Hidden Heroines: Lady Rhondda | BBC Wales

By Paul Ewans

Harry Stopes-Roe was one of the most tireless and dedicated humanist campaigners of the 20th century. Son of the influential […]

Margaret Chappellsmith was a devotee of the socialist and secularist ideas of Robert Owen, becoming one of the Owenite movement’s […]

With all the pretensions of spiritualists… No great truth containing a benefit to humanity has ever reached us; no addition […]

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]