I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as members, or lecturers, or visitors, have fluttered in and out of Larner Sugden’s red-brick temple for more than a generation, and helped to preserve the soul of Leicester from decay and dullness.

F.J. Gould, in The Freethinker (1918)

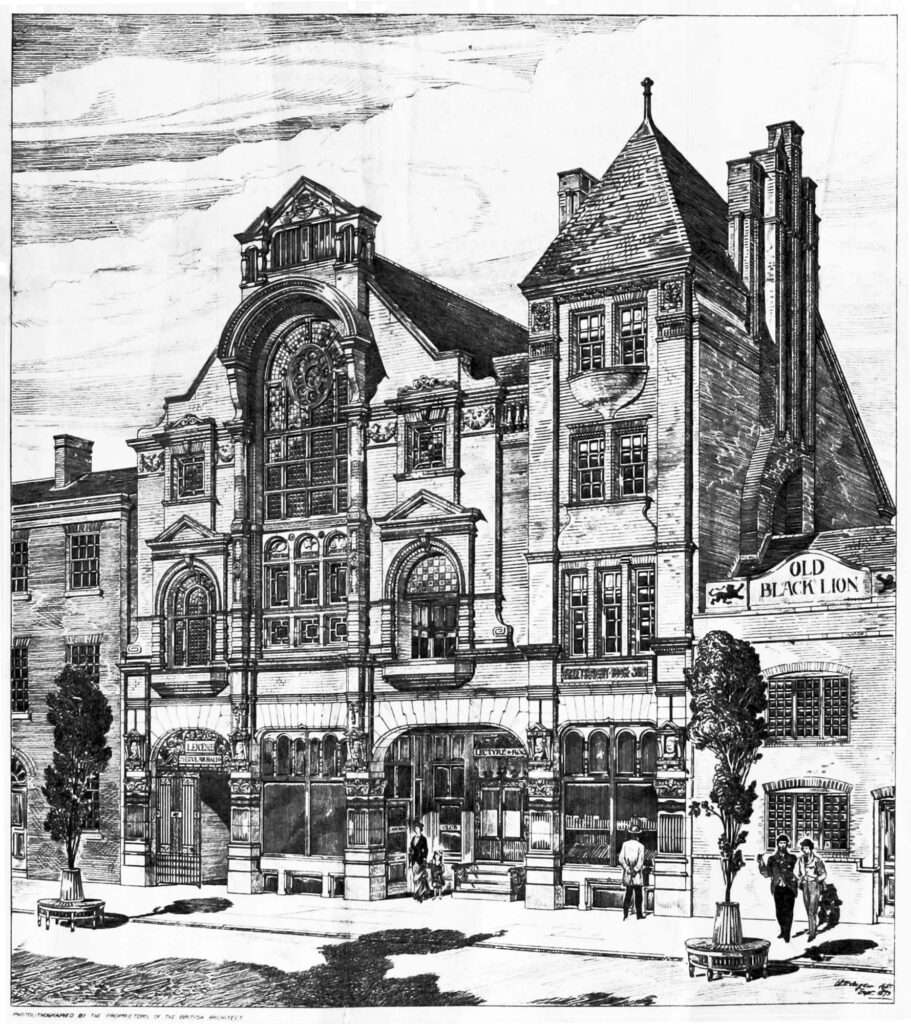

The Leicester Secular Hall was opened in 1881, built as the official home of the Leicester Secular Society. The hall was designed by William Larner Sugden, an architect and friend of William Morris. Leicester’s is the only surviving provincial Secular Hall, and has been used continuously by the Secular Society since its opening. Speakers over the years have included Charles Bradlaugh, Annie Besant, Harriet Law, George Bernard Shaw, James Ramsay MacDonald, Bertrand Russell and numerous others.

These were small groups but were profoundly important. They were the crucibles of creation. What is now the commonplace thinking of universities, of established philosophers, of recognised sociologists, even of some religious leaders, was first discussed by these few.

Fenner Brockway, Preface to A Century of Progressive Thought: The Story of Leicester Secular Society (1972)

The origins of the Secular Hall lay in the frequent struggles of secularist and radical groups to find willing hosts for their meetings and lectures. As Gillian Hawtin has written:

Secularist lecturers were frequently in the ’40s and ’50s denied the use of Halls. Apart from the fact that the most commodious were often attached to religious bodies, clerical authorities put pressure on lay landlords and cases of broken contracts are fairly frequent. A room over the bar was not unusually engaged, but publicans were afraid for their licenses. These difficulties led to a movement among Secularists to build their own meeting places, from the pennies of the infidels, much as the coppers of the believer built the ubiquitous non-conformist chapels of the same era.

Although this was becoming less frequent in the latter half of the 19th century, after George Jacob Holyoake was denied the use of a public room for a lecture, Josiah Gimson proposed the building of a dedicated secular hall. On Sunday 18 November 1872, a first collection was taken in aid of the scheme, and shortly afterwards came the formation of Leicester Secular Hall Company: formally constituted on 2 May 1873. Gimson, an engineer, councillor, and President of Leicester Secular Society, was the majority shareholder, with others – notably Holyoake – also making significant contributions.

A plot of land was purchased , and a portion of the ground set aside for the Hall. Building began in 1879, the architect being William Larner Sugden of Leek, Staffordshire. The building was completed in 1881, embodying at Humberstone Gate what F.J. Gould described as

an assertion of the principle that human destiny is shaped not on the knees of the gods but in the hearts and brains of men and women.

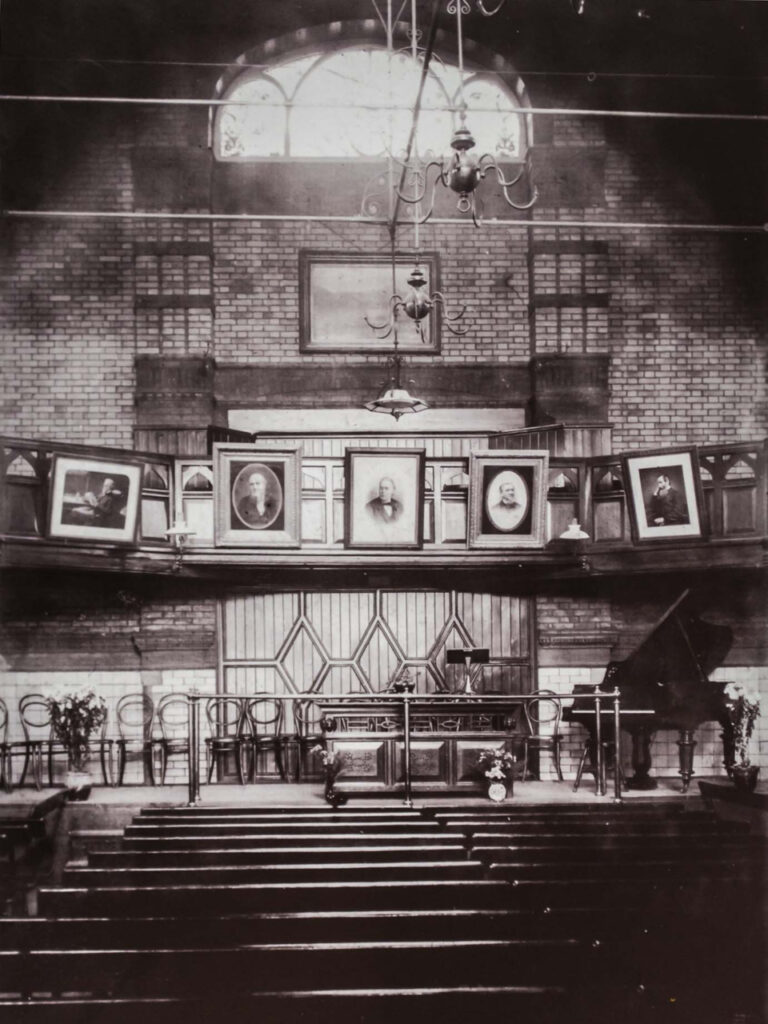

The first floor contained a lecture hall, with galleries at each end, a lecturer’s room, ladies’ room, and another room for use as a bar for refreshments. The ground floor featured a club room and bar, a committee room, and a freethought book shop. The basement space allowed for recreational activities, such as bowling and billiards.

Adorning the front of the Secular Hall were five busts, commissioned by Josiah Gimson and sculpted by Ambrose Louis Vago. These depicted Socrates, Jesus, Voltaire, Thomas Paine, and Robert Owen, all standing – as Gould noted – ‘for wholesome criticism, for revolt against priestly pretensions, and for endeavours after a happier social environment.’ Above them were panels symbolising the values of the Society and Hall: Libertas, Justicia and Veritas (Liberty, Justice and Truth).

The Secular Hall opened on Sunday 6 March 1881. Writing fifty years later, Sydney Gimson recalled the ‘three meetings, morning, afternoon and night’ and retained a ‘vivid memory of the excitement and rejoicing that characterised each’. These meetings were addressed by leading lights of the secularist movement: George Jacob Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh, Annie Besant, and Harriet Law. Norwich’s R. A. Cooper also spoke, and a poem written for the occasion by James Thomson was read.

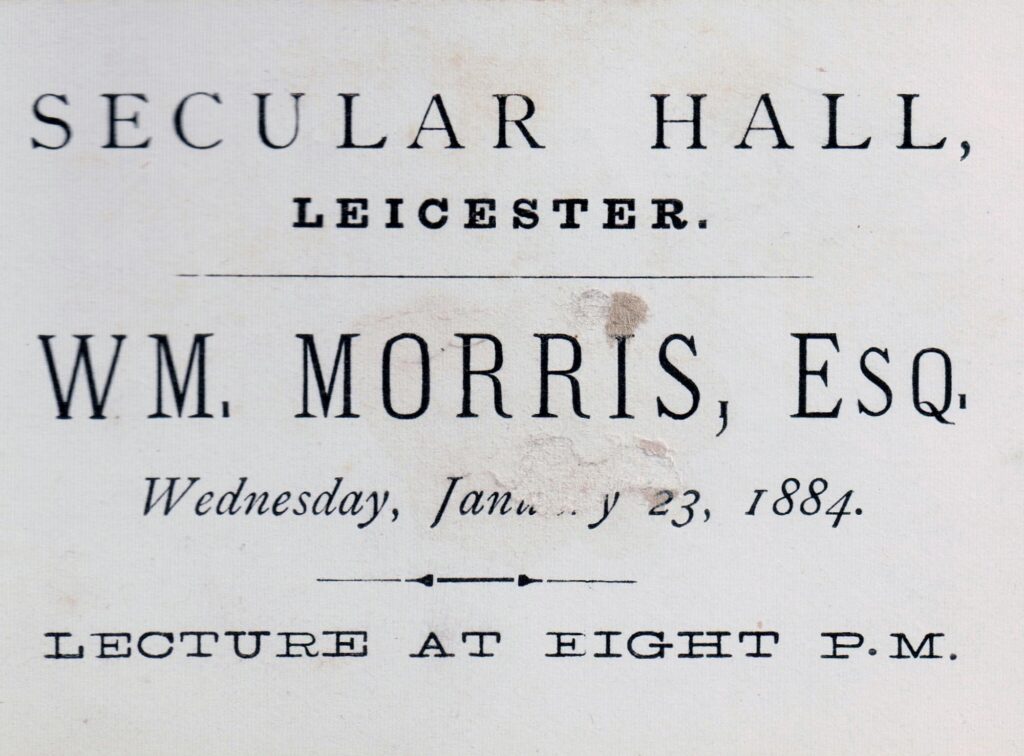

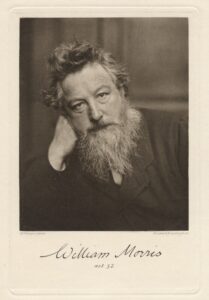

Speakers in subsequent years included those above, as well as G.W. Foote, Charles Watts, and the little remembered Framjee Feroza. Feroza, wrote Gimson, was ‘one of the most eloquent and forceful speakers I have ever heard. One could never forget the effect of one of his philosophical lectures, a joy to listen to and convincing in argument. Others who spoke there were Harry Snell, Chapman Cohen, Eleanor Marx, Henry Crompton, and William Morris. As the Secular Society had done since the 1850s, the Secular Hall continued the tradition of bringing advanced thinkers before the wider public. In 1884, William Morris delivered his famous lecture ‘Art and Socialism’ at the Hall, and Fenner Brockway would recall in 1972 the joy of hearing there ‘the exponents of new thought, putting aside dogmatism, seeking only the truth.’

The space and its speakers stood for self-determination, investigation, and human possibility; advancing humanist values and the principles of secularism. Leicester Secular Hall continues this tradition today, providing a programme of talks, and highlighting the value of knowledge, discussion, and inquiry.

Mary Holland was a doyenne of Irish journalism. She epitomised the highest journalistic standards – she inquired, she informed, she […]

Fellowship is heaven, and lack of fellowship is hell. William Morris, A Dream of John Ball (1888) Painter, textile designer, artist, […]

You can always appeal to common decency, which the vast majority of people believe in without the need to tie […]