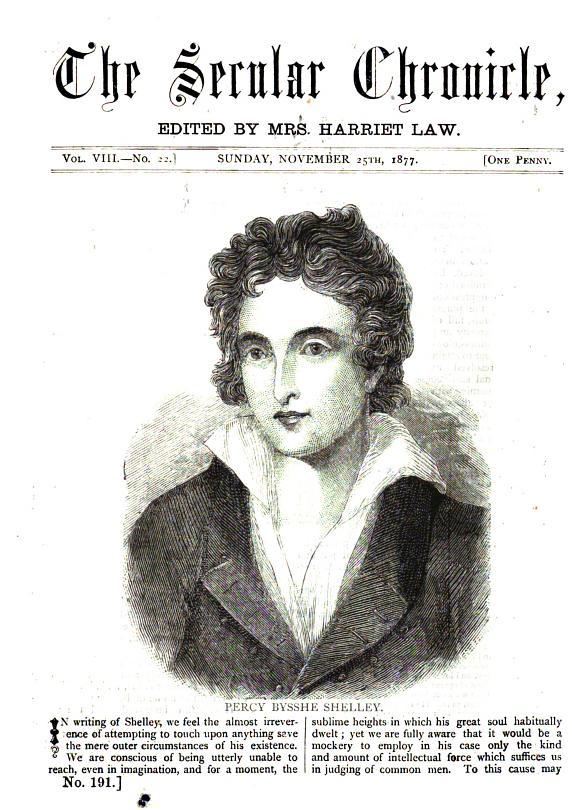

Percy Bysshe Shelley was a major poet of the Romantic period, and remains one of England’s best loved and most influential writers. Despite being born into a wealthy family, Shelley chose to pursue a passion for writing, leading to financial uncertainty and familial estrangement. Shelley’s was a humanist creed of love for humankind, respect for nature, and equality for all, expressed in work which was considered radical and dangerous: promoting atheism, rebelling against authority, and expressing the desire for greater freedoms for everyone. Though his life was short, he made a tremendous impact on the thinking of his time.

Percy Bysshe Shelley was born on 4 August 1792 in Horsham, Sussex. Shelley’s grandfather, Sir Bysshe Shelley, was a peer of the realm, whose name Shelley inherited. In 1802, aged ten, he started school at the Syon House Academy. He was the subject of bullying by the other school children, primarily due to his inability to control his temper and poor fighting skills. Despite being bullied Shelley did have enjoyable memories at the school. He gained an interest in science lectures given by Adam Walker, whose lessons focused on electricity, astronomy, and chemistry. He also started to read and became interested in gothic literature.

In 1804, at the age of twelve, Shelley continued his education at Eton College where his love for literature increased dramatically. It was during his time at Eton that Shelley read the likes of Plato, Pliny, and Lucretius, alongside modern poets such as Robert Southey. Such literature developed Shelley’s atheism, which led to further bullying. He was often called ‘Mad Shelley’ or ‘Shelley the Atheist’. Shelley was at Eton for six years, by the end of which he had had some of his poems published and written a gothic novel called ZastrozziI.

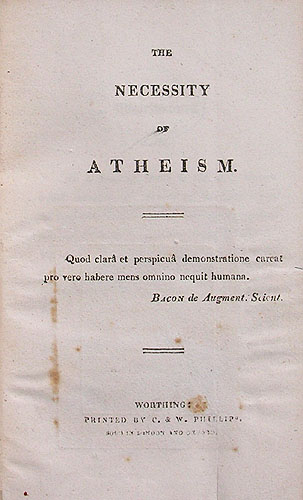

Shelley went up to University College, Oxford in 1810. However he spent only a year at the university. In 1811, he published the pamphlet The Necessity of Atheism, which argued that ‘Every reflecting mind must allow that there is no proof of the existence of a Deity’. Extremely radical and in direct contradiction to the teachings of Oxford, the pamphlet led to Shelley’s expulsion from the University. Shelley’s relationship with his family was also damaged and would never properly recover.

If the knowledge of a God is the most necessary, why is it not the most evident and the clearest?

Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Necessity of Atheism (1811)

Shelley felt that his time would best be spent writing poems and pamphlets questioning the authorities of England and the Church. This he saw as a service to humanity. With this approach to life, and sympathetic to the cause of Catholic emancipation, Shelley yearned to travel to Ireland. In 1812 he published An Address to the Irish People followed by Proposals for an Association of those Philanthropists. Once in Ireland Shelley wrote further pamphlets, including An Address and the Proposals in Declaration of Rights (1812). Each of these pieces contained radical ideas, however did not encourage violence and advocated for patience. For financial reasons, his time in Ireland was cut short, and he returned to London in 1813.

Shelley’s first significant poem, Queen Mab, was written when he was eighteen. It was all about ‘integrity and loveliness’, about the evil of tyranny in any form, and ‘suicidal selfishness’. Amongst other things, it attacked established religion, and its content was so shocking that it had to be published privately. Even then, legal proceedings were taken against the publisher.

Shelley’s ideas ran directly counter to those of his time, when a few were held to be rightfully in authority and the many were supposed to do what they were told without question. Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy (written in 1819 after the Peterloo Massacre) expressed his opposition to these ideas unequivocally:

Men of England, heirs of glory,

Heroes of unwritten story…

Rise like lions after slumber

In unconquerable number.

Shake your chains to earth like dew

Which in sleep had fallen on you.

Ye are many, they are few.

Shelley always argued in favour of free speech and tolerance; he optimistically ended an open letter (intended for publication) with the words:

The time is rapidly approaching… when the Mahometan [Muslim], the Jew, the Christian, the Deist, and the Atheist, will live together in one community, equally sharing in the benefits which arise from its association, and united in the bonds of brotherly love.

Shelley would continue to write political and Romantic poems throughout the last ten years of his life, covering a vast range of human subjects. These encompassed tender and delicate poems such as To a Skylark, and the poetic drama in honour of human freedom, Prometheus Unbound (both published in 1820). He was conscious that half of the human race at that time was denied a public voice, and said that as long as woman remained a ‘bond-slave’ of man, life must remain ‘poisoned at the wells’.

Shelley died in July 1822, while sailing near Lerici, Italy, when his boat capsized. His body was found washed ashore on 18 July 1822. He was 29 years old.

Shelley’s influence as a writer and poet was marked, and his contemporary William Wordsworth described him as ‘the best of all’. Born on the eve of the Terror in France, many drew comparisons between his early work advocating for Irish Catholic emancipation and the revolutionary fervour of the French Revolution, creating fear in the established authorities in the UK. But Shelley was unafraid of courting controversy in the name of championing freedom.

One of his poems, Ozymandias, especially emphasises the futility of dictators who set themselves up as supremely important, only to have all their vain show wiped out by the passage of time. Shelley imagines a traveller in the desert who happens upon the remains of a huge statue, now broken, forgotten, half buried in the sand. Among the remains, the traveller reads an inscription:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Greatness, Shelley taught, lies not in the power a person may snatch for personal glory. It lies rather in caring for one another and for nature, from which alone a universal quality of life can spring. That message is as true for our times as it was for his.

By Louis Holmes

I was not, and was conceived. I loved and did a little work. I am not and grieve not. Epitaph […]

In common with other humanists, I believe that the only possible basis for a sound morality is mutual tolerance and […]

Throughout his life, Professor of Philosophy, John Muirhead, sought to put his ethical principles into practice. Indeed, whilst philosophers are […]

I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as […]