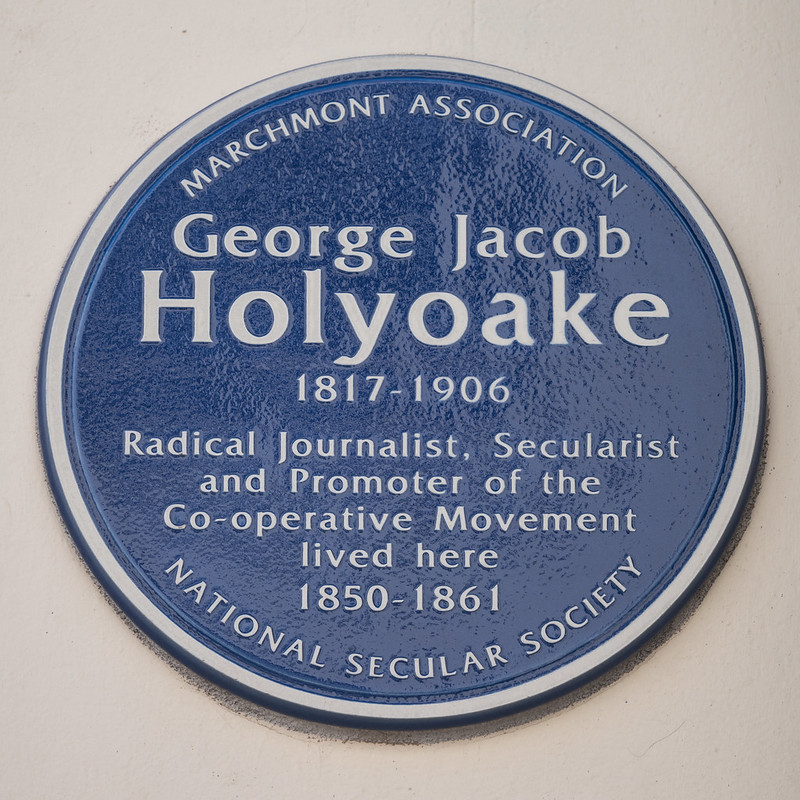

On Woburn Walk is a plaque to George Jacob Holyoake (1817-1906), a writer, lecturer, and promoter of the Cooperative movement, who coined the term ‘secularist’ in 1851.

For Holyoake, secularism described ‘that province of human duty which belongs to this life’. It meant:

promoting human welfare by material means; measuring human welfare by the utilitarian rule, and making the service of others a duty of life. Secularism relates to the present existence of man, and to action, the issues of which can be tested by the experience of this life.

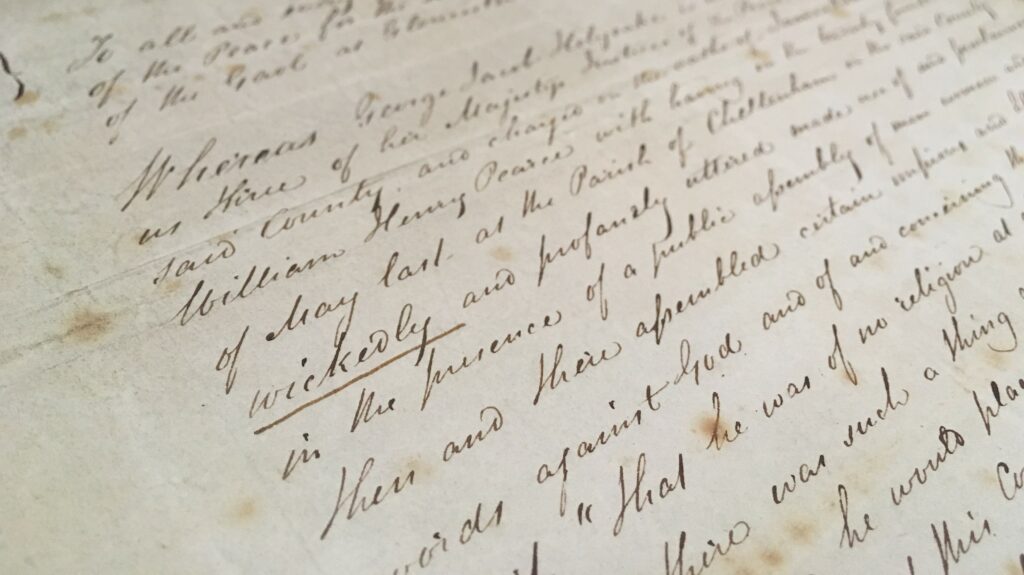

In its focus on living well in this life, without hope of another, Holyoake’s definition of a secularist is almost identical to that of a humanist today (while the term ‘secularist’ has come to describe a political position – one that argues for the separation of church and state, freedom of religion and belief, and equal treatment of all regardless of religion or belief). Holyoake’s own efforts towards the betterment of society were focused on the promotion of cooperation, and a fearless defence of the right to free thought and discussion. In 1842, he had been arrested in Cheltenham while lecturing on the social philosophy of Robert Owen (1771–1858), when he responded to a question from the crowd by suggesting that he would ‘place the Deity on half-pay’. His trial in August of that year resulted in six month imprisonment, the last trial for blasphemy in England but by no means the first. Among the many others tried and incarcerated on charges of blasphemous libel in the first half of the nineteenth century were Richard, Mary Ann and Jane Carlile, Matilda Roalfe, Thomas Paterson, Emma Martin, and Charles Southwell – all of whom advocated for the freedom to criticise political and religious structures.

Holyoake’s daughter, Emilie Ashurst Holyoake, followed in his footsteps as a promoter of the cooperative movement and trade unionism, particularly among working women. Emilie believed in the ‘Piety of usefulness rather than the usefulness of Piety,’ and was a member for many years of the West London Ethical Society. His brother, Austin Holyoake, was a printer and publisher, as well as the writer of non-religious marriage and funeral services.

Close by, a plaque remembers pioneering modernist writer Dorothy Richardson (1873-1957), whose stream of consciousness narrative style was an innovation often compared to another Bloomsbury resident and humanist, Virginia Woolf.

Pelagius lived between the fourth and fifth centuries, and advocated a heretical Christianity that emphasised free will and humanity’s capacity […]

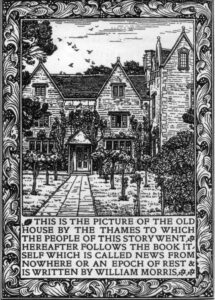

Kelmscott Manor was the country home of the writer, designer, and socialist William Morris from 1871 until his death in […]

Sophie Bryant was an Anglo-Irish mathematician, feminist, suffragist, teacher, and promoter of moral education. She played a key role in […]

Harriet Martineau described her escape to atheism like this: “I lingered long on the stages of speculation and taste, but […]