Under its successive names, adopted or given… is traceable a constant endeavour to study carefully, and keep abreast of, the growing knowledge of the world, at whatever cost to traditional prejudices or opinions; to do this in a spirit of tolerance no less than of sincerity.

Moncure Conway, Centenary of the South Place Society (1893)

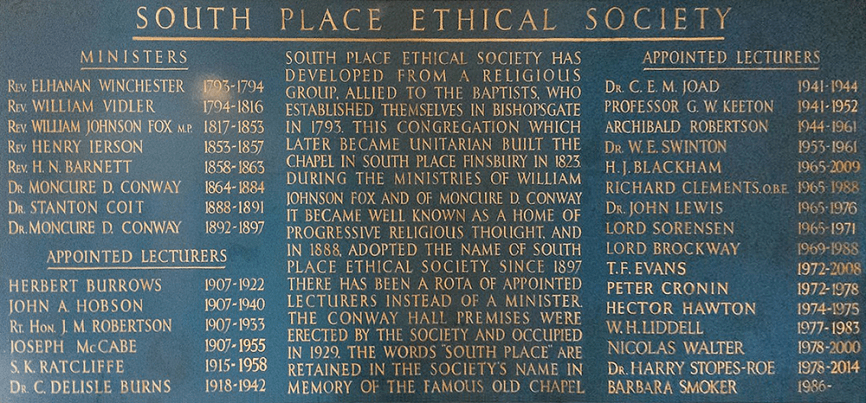

The group that became South Place Ethical Society began in the late 18th century as a dissenting congregation, who rejected the doctrine of eternal damnation. Over the following 200 years, led by a succession of liberal religious thinkers, the group evolved from universalism, through Unitarianism, to humanism. Central to this story were Elhanan Winchester, William Johnson Fox, and Moncure Conway, who each saw the society through periods of change and adaptation. With the arrival of Stanton Coit in 1888, South Place officially became an ethical society: confirming the humanist outlook retained today at Conway Hall.

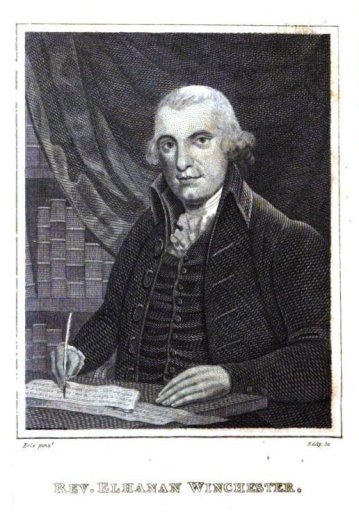

South Place Ethical Society began as a small congregation led by the American minister Elhanan Winchester, who gathered in their first official premises in Bishopsgate, London on 14 February 1793. Winchester and his followers rejected the notion of eternal damnation, which condemned sinners in life to torture and torment in death, and named themselves the Philadelphians, or ‘loving brothers’. United by a creed emphasising divine love rather than threatening punishment, this early incarnation also laid down some of the values that would remain true for the group throughout subsequent changes in leadership and belief. Winchester for example, denounced the slave trade, and capital punishment. In this, wrote later leader Moncure Conway, ‘he instituted a true Ethical Society’.

The society’s second leader was former Baptist preacher William Vidler, who had converted to universalism: the belief, shared by Winchester, that all human beings will be saved (or ‘universally restored’), rather than condemned by God. Vidler led the group until his death in 1816, during which time he published a periodical (the Universalist Miscellany, or Philanthropist’s Museum), decried cruelty to animals, and increasingly emphasised openness, inclusiveness, and freethought within the congregation. This laid the groundwork for the society’s next leader, William Johnson Fox, and the introduction of Unitarianism. Fox sought to establish ‘Virtue and not Faith for the bond of union’, prefiguring the aims of the Ethical movement by over half a century.

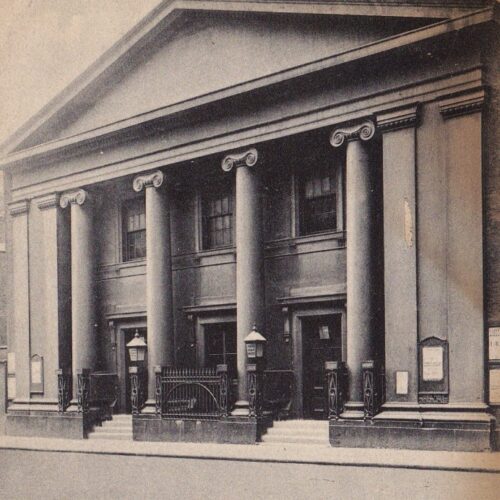

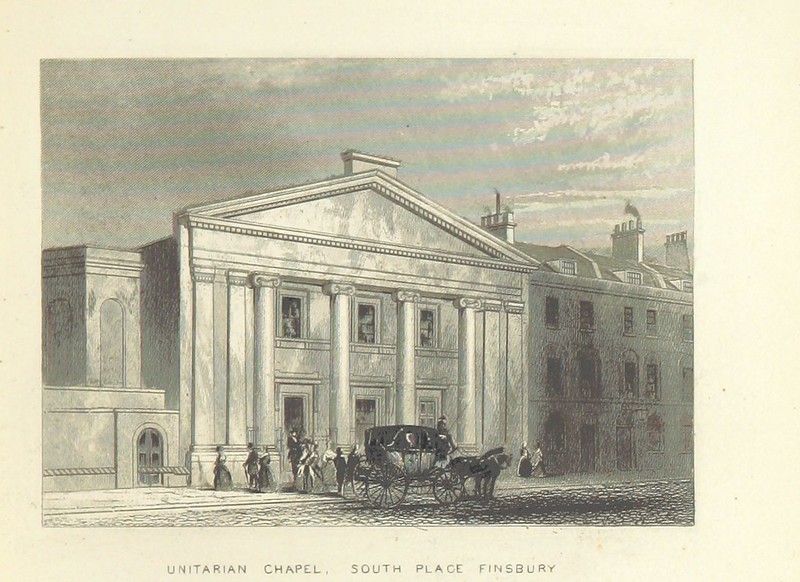

Under Fox’s leadership, the chapel at Parliament Court (which was registered as a Unitarian chapel in July 1817) began to host evening lectures on a variety of political and social subjects. Fox was a vocal advocate of free speech, defending the rights of those of all faiths and none (notably Richard Carlile) to express their views without persecution. Fox also urged a Dissenters’ Marriage Bill, which would remove the requirement for nonconformists to be married in an Anglican church, and spoke in favour of divorce. On 22 May 1823, Fox laid the first stone of South Place chapel in Finsbury, using his speech to emphasise the enduring values of truth-seeking, good works, and ‘usefulness on earth’. South Place chapel opened 1 February 1824, its trust deed stating that it would serve:

as a place for the public religious worship… at such times, according to such forms, and under such regulations as are now adopted, or shall from time to time be adopted by the said Society.

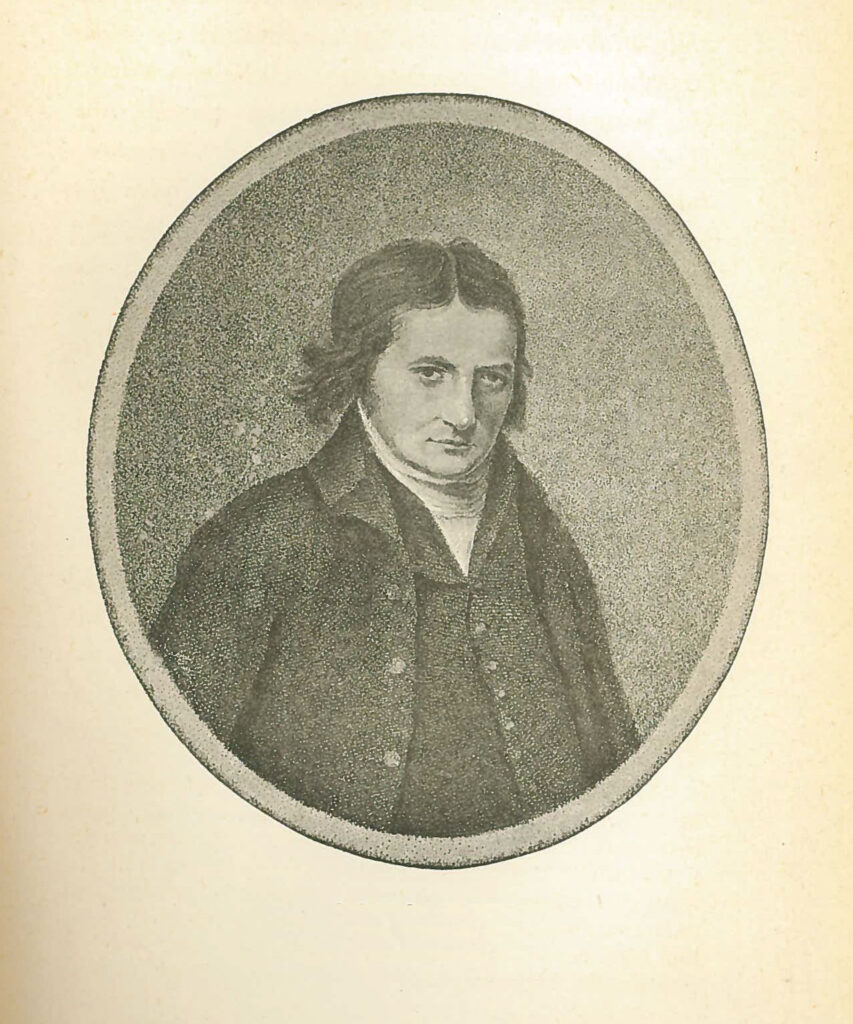

The vibrant social circle at South Place became home to a number of influential freethinkers and humanists, who were themselves influenced by Fox’s radicalism and inclusiveness. Among them were Harriet Martineau, John Stuart and Harriet Taylor Mill, George Jacob Holyoake, and Elizabeth Malleson, founder of the Working Women’s College. Fox’s successor, Moncure Conway, continued the tradition of social relevance and cultural connection, himself a friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson at home in America, and literary agent to Mark Twain in London. As leader of South Place from 1864, wrote Conway:

Literature as well as religion, science, art, philosophy, sociology, history – the boundless continent of human interests was mine. Here I could freely, fully pour out my soul. What joy was that!

Conway, an abolitionist, suffragist, and rationalist, increasingly shed religiosity and embraced humanism, and the society followed. In 1888, Stanton Coit – Conway’s choice for successor – agreed to take over at South Place on the condition that it became an ethical society. When Conway resumed his role in 1892, South Place was firmly established within the growing network of the early organised humanist movement, and on his retirement in 1897, the position of ‘minister’ was replaced by that of appointed lecturer.

Since that time, the society has played host to a vast array of progressive thinkers, reformist movements, and meetings of international note. In September 1929, the society’s purpose-built premises were opened in Red Lion Square, named for Moncure Conway. Today, it is home to the Humanist Library and Archives, and continues to stand for freethinking, culture, creativity, and kindness.

Bessie Mabbs was a teacher, school principal, and active member of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK), chairing […]

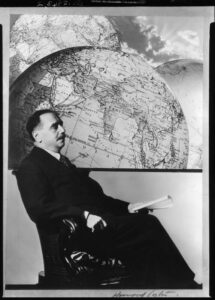

The Progressive League was an organisation dedicated to the advancement of scientific humanism, founded by author H.G. Wells and philosopher […]

We have the faculties for gaining knowledge; and Rationalism will always maintain that we are at liberty to use them […]

It is with a feeling of considerable deprecating delicacy that I venture to write of this woman, whom I so […]