There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… All things that are, are ours. But we must care. For if we do not care, we do not exist.

Terry Pratchett, Reaper Man (1991)

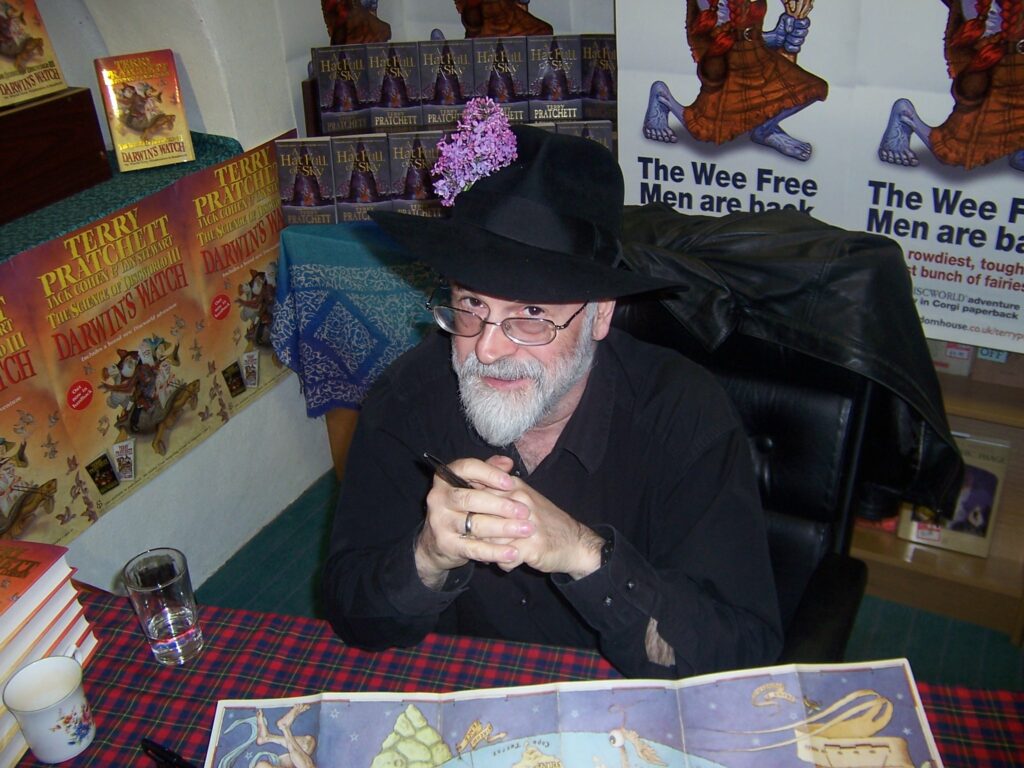

Terry Pratchett was a beloved author and prominent humanist, renowned for his satirical and humorous fantasy novels, particularly the Discworld series. In later life, he became an eloquent advocate for the right to die with dignity, turning his characteristic wit and compassion towards the campaign for assisted dying. A patron of Humanists UK and an active champion of many of its campaigns, he was awarded the Humanist of the Year award in 2013.

Terry Pratchett was born on 28 April 1948, in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. His passion for writing and storytelling developed early, and he left school at 17 to begin a career in journalism.

Pratchett’s breakthrough came with The Colour of Magic (1983), the first novel in the Discworld series, which humorously explored a flat, disc-shaped world supported by four elephants standing on the back of a giant turtle. Over the course of his career, Pratchett wrote over 40 Discworld novels, each offering a unique blend of fantasy, satire, and insightful commentary on the human condition. They also offered insight into Pratchett’s personal philosophy. As Andrew Copson wrote:

His humanism showed itself in his work in many ways. When asked for an example of this himself, he cited his story The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, in which the mice invent morality before they invent religion. That summed up Terry’s view on morality and religion. Morality came first: it was a natural development of society. He did not see ethics as coming from outside of human beings, but instead from the bonds we shared and as a product of human beings living cooperatively together and trying to promote happiness.

In Small Gods (1992), Pratchett satirised religion. Deities compete for human beings’ belief, without which they are nothing. Religion becomes centred around institutions, and power corrupts. Historic conflicts between religion and science are flipped for philosophical (and comedic) effect: everyone knows the Discworld is flat and that the sun orbits around it, but Omnian doctrine insists that the world is round and orbits the sun.

Pratchett’s humanism shines through in his writing. On science, religion, and politics, he was able to find poetic and poignant ways to address what mattered:

On evolution:

I would much rather be a rising ape than a fallen angel.

On belief in miracles:

Humans!… what impressed them? Weeping statues. And wine made out of water!… As if the turning of sunlight into wine, by means of vines and grapes and time and enzymes, wasn’t a thousand times more impressive and happened all the time.

Terry Pratchett, Small Gods (1992)

On human responsibility:

There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… All things that are, are ours. But we must care. For if we do not care, we do not exist.

Terry Pratchett, Reaper Man (1991)

And on the importance of human connection:

“And what would humans be without love?”

RARE, said Death.

Terry Pratchett, Sourcery (1988)

Beyond his literary contributions, Terry Pratchett was known for his public advocacy. He was a prominent humanist voice, emphasising reason, science, and compassion as the basis of his worldview, and supporting a number of Humanists UK’s campaigns.

One of the most significant aspects of Pratchett’s later life was his advocacy for assisted dying. Diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2007, he became a vocal supporter of the right to die with dignity. Pratchett documented his journey with Alzheimer’s in the BBC documentary Terry Pratchett: Choosing to Die (2011), which explored the complexities of assisted dying. He argued for legislation allowing individuals the choice to end their lives when faced with terminal illnesses and diminishing quality of life.

Terry Pratchett’s advocacy extended to his involvement with organisations such as Dignity in Dying and Humanists UK. He used his platform to raise awareness about end-of-life choices and to prompt frank discussions around assisted dying. Pratchett’s own struggle with Alzheimer’s and his determination to maintain control over his destiny added a personal and poignant dimension to his advocacy. His support for the right to die was inextricably linked to his humanism and his belief in the essential dignity and rightful autonomy of human beings. He argued: ‘If I knew that I could die, I would live. My life, my death, my choice.’

Terry Pratchett died on 12 March 2015, leaving a remarkable literary legacy, and a model of profound humanism. As Pratchett himself wrote:

no-one is finally dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away – until the clock he wound up winds down, until the wine she made has finished its ferment, until the crop they planted is harvested. The span of someone’s life, they say, is only the core of their actual existence.

Terry Pratchett, Reaper Man (1991)

It is said that your life flashes before your eyes just before you die. That is true, it’s called Life.

Terry Pratchett, The Last Continent (1998)

Terry Pratchett is remembered today for his literary contributions, his wit, and his courage. His advocacy for assisted dying and his openness about his own experiences with Alzheimer’s continue to influence conversations about compassion, autonomy, and assisted death, while his books are still widely read, loved, and discovered.

BHA mourns patron Terry Pratchett | Humanists UK

Sir Terry Pratchett – Shaking Hands with Death | Lecture for the Royal College of Physicians (2010)

Terry Pratchett’s Humanist Funeral | Kenneth Greenaway

Main image: Sir Terry Pratchett by Steve James. Licensed CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Though hearing and discussing many philosophies and keeping open minds, many, if not most of us had a slightly utilitarian […]

Charles Albert Watts was a lifelong promoter of rationalism, and the founder in 1885 of Watts’s Literary Guide, still published […]

Mary Edith Durham was a writer, artist, and anthropologist, who became well known for her work on Albania. She was […]

With all the pretensions of spiritualists… No great truth containing a benefit to humanity has ever reached us; no addition […]