The gist of heresy is free personal choice in act, and specially in thought – the rejection of traditional faiths and customs.

Jane Harrison, ‘Heresy and Humanity’ (1909)

The Cambridge Heretics was a society formed at the University of Cambridge in 1909, in opposition to compulsory worship, and in celebration of humanist values. Members and speakers devoted themselves to the rejection of assumed authority and religious creed, presenting and discussing papers on themes of religion, philosophy, and art. Over the course of its existence, the Cambridge Heretics welcomed a remarkable number of speakers and Honorary Associates, exercising significant – but largely overlooked – influence on some of the early 20th century’s leading thinkers.

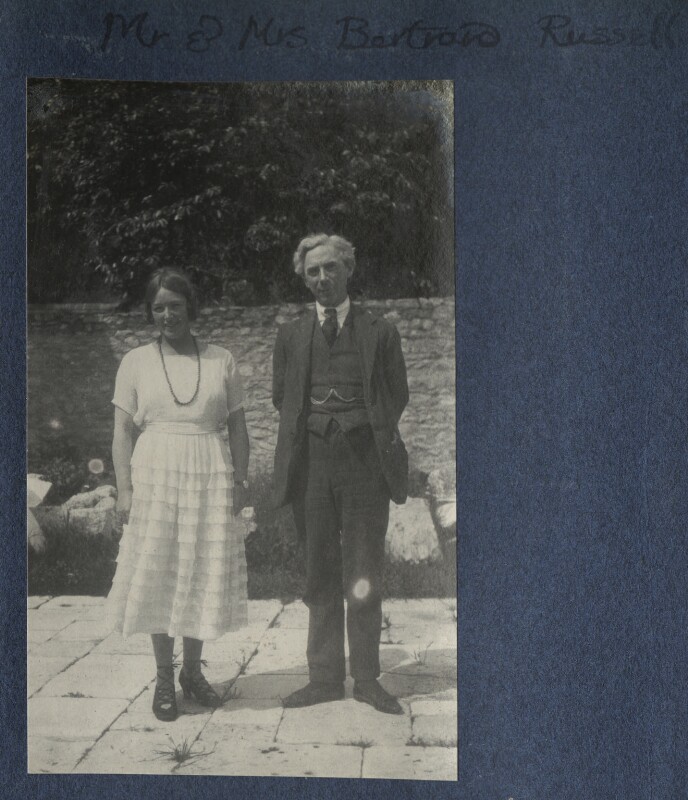

Its members included Dora and Bertrand Russell, C.K. Ogden, Francis Darwin, and John Maynard Keynes. Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Rupert Brooke, G. E. Moore, George Bernard Shaw, Rebecca West, Eileen Power, Roger Fry, and Ludwig Wittgenstein were just some of a lengthy list who presented papers to the Heretics between 1909–32.

C.K. Ogden, who was the prime mover in the Heretics, was to become one of my real friends and a considerable influence in my life. He had a flat high up in Petty Cury, which he called Top Hole. It was here that the Heretics used to meet. I used to bicycle off there of a Sunday evening with a most agreeable feeling of defiance and liberation.

Dora Russell, The Tamarisk Tree: my quest for liberty and love (1975)

The Society was formed in the wake of a publication by Cambridge Master William Chawner, entitled Prove All Things. The paper, read before the university’s religious discussion society and privately circulated, sparked a flurry of indignant responses. One opponent wrote:

Regarding a don with a certain amount of reverence they [students] naturally swallow the agnostic reasoning, if it comes from you and, excuse my saying it, I think it a distinct abuse of your position. You have no moral right to upset a boy’s religious beliefs unless you have a higher religion to offer him, and you have only nebulous philosophic theories to offer instead.

Chawner published a collection of responses (positive and negative) as a supplement to his paper. One, signed by 12 undergraduates, requested copies of the offending text. This dozen became the first members of the Cambridge Heretics. Their inaugural meeting in December 1909 was addressed by metaphysician J.M.E. McTaggart, and classicist Jane Ellen Harrison, who spoke on the virtue and duty of heresy:

Heresy, the Greek hairesis, was from the outset an eager, living word… always in the word is hairesis there is this reaching out to grasp, this studious, zealous pursuit… Only in an enemy’s mouth did heresy become a negative thing.

Heresy, Harrison argued, was the ‘child of Science’, but science alone did not make the heretic. Humanity was just as important: ‘sympathy with infinite differences, with utter individualism, with complete differentiation’. Heresy, Harrison contrasted with the repressive, herd instinct. Heresy was striving, as individuals but in cooperation, towards a better, freer world. ‘In a word’, she said:

If we are to be true and worthy heretics, we need not only new heads, but new hearts, and, most of all, that new imagination, joint offspring of head and heart with is begotten of enlarged sympathies and a more sensitive habit of feeling. About the moral problem there is nothing mysterious; it is simply the old, old question of how best to live together. We no longer believe in an unchanging moral law imposed from without. We know that a harder incumbency is upon us; we must work out the law from within.

From the first meeting onwards, the Heretics held regular public and private meetings, and by 1913 had a membership of over 200. Women students from Newnham College were able to join from the outset, but Girton’s were initially prevented by chaperonage rules. However, botanist and Honorary Fellow of Girton Ethel Sargant later stepped in, and the Society’s 100th meeting (in January 1913) was a party at her home.

The Heretics’ first Secretary was psychologist, writer, and philosopher Charles Kay Ogden, who became its President in 1911, and remained so until 1924. He was succeeded by economist Philip Sargant Florence, who would also become a longtime Vice President of the Ethical Union (now Humanists UK). In a history of the Society published in The Humanist Outlook (1968), Florence credited Ogden’s ‘sense of fun’ with helping ‘infectiously to spread heresy and Humanism’, creating heretics ‘among at least six generations of Cambridge men and women’. Given that chapel attendance remained compulsory (‘a mild and gentlemanly attempt to repress complete freedom of thought and enquiry’, in the words of F.M. Cornford), the Heretics provided a vital release for many. Dora Russell, the Society’s Secretary 1918-19, later wrote of its liberating influence on her.

Although Cambridge’s most frequently referenced Society is the secretive and selective Apostles, the Heretics are no less worthy of attention. In Modernist Heresies, Damon Franke argues that the influence of the Heretics on modernism has been gravely overlooked:

… until the Society’s dissolution in 1932, [the Heretics witnessed] an impressive and diverse set of lectures by scores of influential modernists. There are the philosophers, Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, James McTaggart, Ludwig Wittgenstein. John Maynard Keynes stood at the forefront of the Economics Section. Bernard Shaw was perhaps the most famous literary figure. Jane Harrison brought cultural anthropology into the fold. But if you were to name any famous modernist figure from W.B. Yeats to E.M. Forster to F.T. Marinetti to Marie Stopes, it is remarkable how many were members of the Heretics or in dialogue with this group.

As Dora Russell recalled, at the Heretics ‘our weapons were ideas and talk and the knowledge that heresy is contagious’. The Society gave generations of students and staff, including some of the most influential thinkers of the 1920s and 1930s, permission to debate and dissent openly. Closing his history of the Society for The Humanist Outlook, Philip Sargant Florence noted:

In 1956, Julian Huxley hailed the change of title of the Literary Guide to the Humanist ‘as attaching importance to all essential human attributes and values, morality as well as science, art as well as reason.’

Four decades earlier, concluded Florence, the Heretics had already been doing just that.

Modernist Heresies: British Literary History, 1883–1924 by Damon Franke

The Humanist Outlook (1968), ed. A.J. Ayer

We hold that only by making happiness for those around us, and by endeavoring, individually, to make the world a […]

Socialism emerged, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, as a humanist ideal of universal emancipation – the ideal […]

The object of this Society is: To increase the knowledge, the love, and the practice of the right. Its bond […]

Avoiding alike mysticism and shallow denial, he was a true Agnostic, anxious not merely to beat down error, but to […]