Humanism is a philosophy of life based on a concern for humanity rather than a belief in god. Humanists believe that this world is all there is, and we should do all we can to make it a better place for everybody.

Humanism: The Great Human Detective Story (1991)

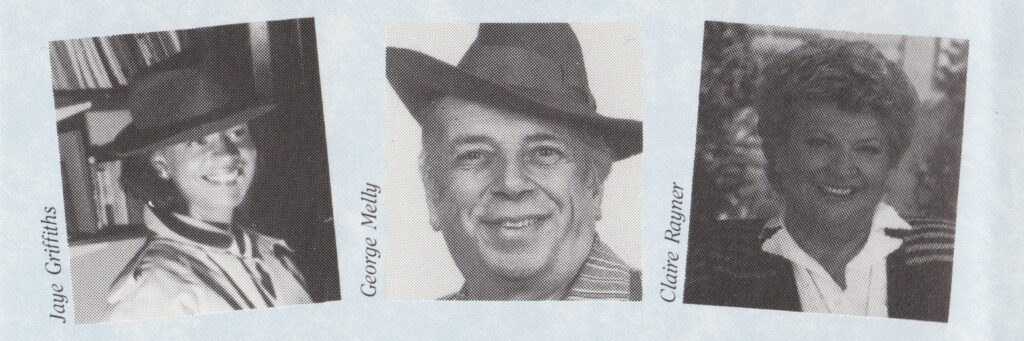

Humanism: The Great Human Detective Story was produced by the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) in 1991, with the aim of introducing ‘the ideas and ethics of the 2,500-year-old Humanist tradition in a clear and concise way suitable for all ages’. The 21-minute film features jazz singer George Melly and agony aunt Claire Rayner, both patrons of the British Humanist Association, who explain their own humanist philosophy and what it means to them. The film explores how humanists make sense of the world, how they live, how they mark significant events, and what they believe about the education of children.

The Great Human Detective Story was scripted by Meredith MacArdle, then the BHA’s Director of Public Relations, and directed and produced by Ian Ilett. Actor Jaye Griffiths took the role of the Detective.

So many questions and so many problems to solve, mysteries to investigate. What am I doing? What am I doing here?

Questions fly at you like mosquitoes. What is the purpose of life? How did the world come about? Why do I feel bad when I hurt someone? Why does it feel good to love someone and help them? No matter who you are, these same old questions keep buzzing around – they never leave you alone. Life can get to be quite a detective story. This is the greatest who dunnit of all.

When we look up at space, our first reaction is wonder. It is totally awe inspiring. We seem so tiny and helpless compared to the universe. It is impossible to take it all in. The universe is so enormous, so complicated, so beautiful. Millions of stars, many of them suns like our own Sun. Millions of planets, just as our own Earth is a planet.

And our Earth: stunning landscapes, each area different, each animal different. As many differences as there are grains of sand. How can all these species of animals and plants each be unique, but each share something basic and wonderful? The pattern for life. And look at human beings, millions of us. We are as mysterious as the universe. We think, we feel, imagine, and wonder, and ask questions. As far as we know, we’re the only form of life to think like this, to be aware of ourselves as individuals, to be aware of others and to feel responsible.

We all share the same questions. Why do I live? How should I live my life? So who dunnit? Well, what are the theories that claim to know something about life? There’s religion, and there’s knowledge based on human understanding and scientific discovery. Religion says ‘god dunnit’, or the gods, or sometimes the goddess depending on which religion you’re talking about. Throughout history, most people never dreamed that the world could be understood in any other way. It seemed obvious that life was carefully planned for divine purposes. But how can people who believe this know for sure, I mean, so and so had a dream, so and so had visions. They believed their god told them what to say and what to write down. They had faith in their god and therefore trusted in the authority of their religion. And their faith gave them a framework of knowledge and understanding about life. But detectives can’t just accept what they’re told. They have to examine all the evidence and look for proof.

So on to other sources of knowledge. Human beings have found out an awful lot of answers themselves just through asking questions and exploring scientifically. You know, scientists are pretty much like detectives: investigating a mystery, looking for clues. They can’t jump to conclusions. They have to beaver away, testing and probing for the truth. And more and more investigations have shown that there are natural processes which made our planet Earth and life on Earth. The laws of physics show how stars and planets came about. The theory of evolution explains how life came about and how, without any supernatural purpose, some species developed, survived better, reproduced better, and other species died out. These processes produced animals with minds, like us. In using their minds to help themselves survive better, our early human ancestors began to develop even further, learning to work together to produce language, culture, knowledge – to become the cleverest, most complicated form of life: us. But the laws of physics are mindless. Evolution is mindless. There was no need for a plan or a purpose.

So, back to our who dunnit. Well, that’s just it. No one ‘dunnit’ at all. Where does that leave us? How do we respond to life? Religion gives answers but scientific inquiry means that we don’t have to accept god and his purpose as fact. The universe seems to have worked without them. Evolution suggests that we are just one of millions of species of life on Earth. So does that mean that there is nothing special about human beings at all? But as an animal species, we are certainly pretty unusual. We don’t just act on animal instinct. We are aware of each other and ourselves; we take responsibility for the way we behave; we are aware of consequences. We can choose; we give meaning to life; and we consider the quality of human life to be the most important thing in life itself. Do religions treat human beings as the most important thing in life? Doesn’t religious belief often obscure the importance we place on caring for each other?

I suppose if everybody believed in the same god, it wouldn’t be so much of a barrier as it is. But the point is that people believe in different gods and frequently – in the name of their particular god – are perfectly prepared to slaughter, torture, burn, tear to bits their fellow man or woman.

Humanism for George Melly, like all humanists, is a guide for life. They subscribe to a scientific approach of examining evidence to understand the world around them. But what is humanism? Is it just non-belief or atheism?

I am a humanist, and I am an atheist, but I don’t think the two terms are interchangeable. Humanism implies a non-belief in the existence of god, but it goes a great deal further than that. It’s how you actually behave once you have established that you don’t believe in god. This I think makes up humanism.

So how do you behave as a humanist? What else makes up your position on life?

I believe that the pursuit of happiness is extremely important, and that happiness depends on certain ways of behaving, non-fanatical ways, taking into account other people’s feelings and needs. And I think the humanist, because he doesn’t believe that everything is preordained by a creator, is in a position more than many believers to try and rationalise life in the practical sense.

Humanism is a philosophy of life based on a concern for humanity rather than a belief in god. Humanists believe that this world is all there is, and we should do all we can to make it a better place for everybody.

Throughout history, most people have been prepared to trust the assumption that their welfare and that of their Earth was in the hands of god. But a tradition of free thinking which looked to the natural world for answers can be traced back to the golden age of classical Greece. A tradition upon which the principles of modern humanism is founded.

Protagoras, Epicurus, and Lucretius: Ancient Greek and Roman philosophers, who created a system of ethics based firmly on human nature and experience. A lot of their understanding was lost in the blaze of early Christianity, but Renaissance scholars of the 15th century, the rebirth of learning, rediscovered wider sources of knowledge. The 17th and 18th centuries began to see science shedding new light on superstition, dogma, intolerance and injustice. Just last century, the social reformer and MP Charles Bradlaugh was called immoral because he insisted on affirming his good intentions in Parliament rather than taking an oath to god. He was thrown out of the Commons several times.

Margaret Knight faced a storm of abuse in the 50s when she broadcast on the BBC her belief that you can be moral without god. And Star Trek, Mr. Spock, Captain Kirk and Captain Picard, all creations of an American humanist, Gene Roddenberry, and all taking the spirit of inquiry where no one has gone before: into the future.

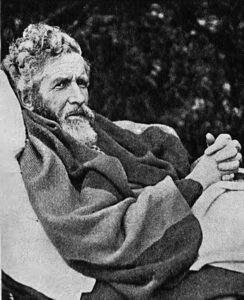

And the spirit of free thinkers, such as Bertrand Russell here, is alive and well today in organisations like the British Humanist Association, and because of its supporters, like George Melly and Claire Rayner.

It’s very difficult to make sure that you stick to the difficult road you’ve chosen for yourself if you’re involved in humanism. Never think it’s the easy way out. There are some people that will tell you that. They say ‘oh, well, it’s hard to be religious. You have to obey the rules and do as you’re told. You have to starve yourself on one day, and not eat things on… And that’s why these people don’t want to be religious. These humanists they’re taking the easy way out’. It’s not an easy way out. It’s a damn sight harder. You never stop thinking: should I? Should he? What should we do? What is best? It’s tough being a humanist but it’s much more, in my experience, satisfying.

But what’s satisfying about being attacked throughout history for being immoral? Many religions say that if you don’t believe in god, you don’t believe in morality.

If there’s one thing that makes me furious, it’s this suggestion that people have to have either carrots or goads to do anything: they can only be virtuous and caring and good if they’re given the promise of an afterlife, a heaven. They can only be prevented from doing something they shouldn’t by being threatened with some terrible hell of some kind or another. Now, there is no difficulty in being good without having a god, if you actually believe that human beings are worthwhile creatures. And if you actually believe as I do, very strongly, that people can be good just for the sheer sake of being good to each other. Altruism to me is as normal and as natural as humour, as curiosity, as bad temper. It’s part of us, it’s part of us. So you don’t have to have a god to care and be moral.

My way of life has no absolute rules. The only one is to, as I say, to do unto others, I suppose, as you would like others to do unto you. To do what’s best for all the people in a particular situation, and all the people include yourself. It’s a constant juggle. It’s half the fun of living! You’re always juggling all these balls in the air, saying ‘oh, gosh, how do I keep that one happy? Oh, gosh, well, if that one has to do without this, maybe that one would be a bit better off’. And that’s how it works.

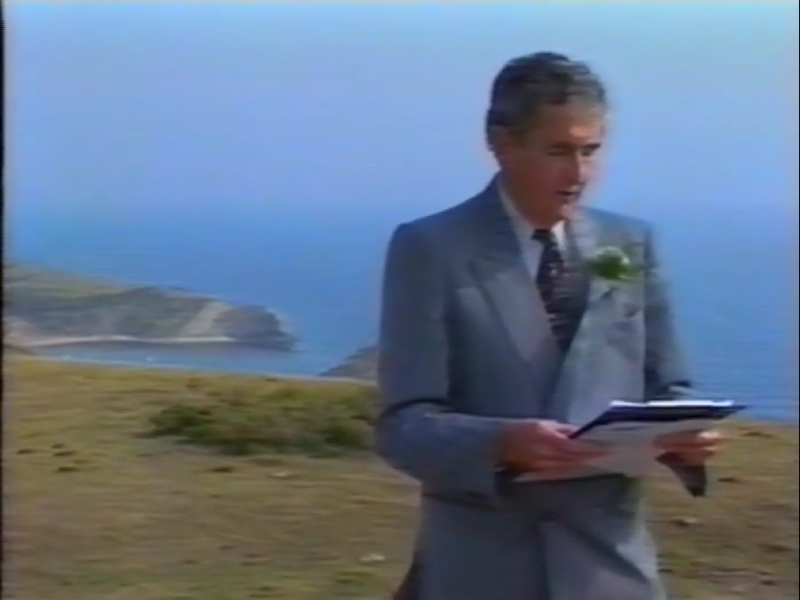

Caring about people and being good are the most positive attributes of human life. It’s what being human is all about. And it leads to loving and caring relationships. It’s only natural that we want to celebrate the closest relationships we form. Religions do not have a monopoly on family ceremonies.

This is a very special occasion. We are gathered here to witness the marriage of Nick and Debbie. That in itself makes it special for them, and for you. It is also special, because here in the open air, with the land, sea and sky around us, unconfined within the walls of church or chapel, we can demonstrate the harmony and unity of man with the natural world. There could be no better place to celebrate a marriage.

Humanist weddings, like this one for Debbie and Nick, take place wherever the couple choose. They say what is meaningful to them. And the music and poetry is chosen by them to celebrate their unity and identity. No ceremony can be more sincere than one based on these choices.

One of the interesting things about this system of thought, and it is a system of thought, is that there can’t be racism. There can’t be sexism, ageism, or any of these isms, because where there is no dogma, there cannot be bigotry. Where you are not separating people into individual bits like mind, body, soul, and all rest of it, you are also not separating them into groups of good people, bad people, religious people, irreligious people. You’re just saying ‘people’.

People often turn to the church for helping coming to terms with death, and for arranging funeral ceremonies. How do humanists deal with the thought of death and what can they do to arrange a non-religious ceremony?

As David had no religious beliefs himself, his family have thought it appropriate to hold a non-religious ceremony. I am therefore officiating today at their request, as a humanist.

The death of each of us is in the order of things. It follows life as surely as night follows day.

I’ve left strict directions that there is to be no religious mumbo jumbo after my death at my funeral. Death as such holds no terrors for me because I am unaware, or disbelieve, that I am to be rewarded with a harp or to burn eternally amongst the coals.

Will you now stand for the committal. To everything there is a season and a time to every purpose on Earth. A time to be born and a time to die.

More and more people are turning to the British Humanist Association for helping arranging dignified, personal, and non-religious ceremonies for funerals, weddings, and namings. But what of the purpose of life?

I don’t feel I’m here as a little pawn in somebody’s game, you know in a great chess game which the devil plays with god, in which one can either be taken or reach the other end of the board. I just think we’re on our own, and must do the best we can. And there’s no headmaster to give us a good or bad report at the end of it.

So, humanism asks questions. It’s honest enough to say it doesn’t have all the answers. Instead of laying down rules, it offers guidelines, and its ethics are to do with enhancing human happiness. It follows scientific, searching principles, but celebrates human feelings. It encourages everyone to take responsibility for their own lives, and to understand what makes things right and wrong. And it doesn’t see any evidence of a god or the supernatural.

How does this guide for life help young people learn and explore their humanity? What sort of education should we offer to our children?

A lot of people think education is putting in. Lift up their little heads, and tamp the facts down, you know, chalk and talk. It isn’t like that. It’s giving people the ability to think and reason for themselves. So there’s a lot of material to put it in, yes. You do actually need facts, but you don’t actually have to learn them by heart. And I think good education for children is to fill them with the belief that their curiosity is justified. Too many children are reared to think that being curious is wrong, that asking questions is being a nuisance, or being cheeky. It should be above all a stimulation of their curiosity and their interest, and their ability to think. No child is incapable of thought. Some children will be slower at it than others. Some will find it difficult to think in words, and will only think in pictures. Some will think in numbers. It doesn’t really matter. Allow them to think and feel and never make them feel guilt about their feelings.

Does that apply also to sex education?

I think it’s terribly important for sex education that children are allowed to have their feelings, because if they’re brought up to think that there is something wrong with their sexual feelings, which they often are, and they’re told ‘oh don’t talk about that’, or ‘it only belongs to older people, it’s nothing to do with you’, when they identify sexual feelings the guilt is monumental. And guilt is corrosive. Guilt sits inside you like acid and burns you up. To have a conscience is one thing to be eaten, to be eaten with guilt is another. So when it comes to sex education, I don’t know why it has to be separate mind you. If you don’t separate it out, then it doesn’t become any big deal. You know, the sky is up, the ground is down, and people make babies.

Children represent the future of humanity. Humanists don’t think there is an immortal soul so, apart from the things they do and create in life, their only immortality is through children. Every day, we are finding out more knowledge and more understanding to give to children, and these abilities to learn and to understand, help us to solve the complex problems of the world today.

The principle of scientific discovery and thinking is very important to humanists. It helps to establish fact from fiction. But science isn’t everything in life. Mr. Spock in Star Trek shows how much human warmth can be lost if you think only about logic and reason. To really make the most of our humanity, we need to develop and express our values, our love, and our desire to help each other. These are what make us humans the unique, special animal we are.

Life would be far more truly envisaged if we dropped the silly phrases “men’s and women’s questions”; for indeed there […]

It has been suggested that matter is capable of destruction, that every atom is destined to be dissolved away in […]

When Nigel Lawson said in 1992 that the National Health Service was the ‘closest thing the English have to a […]

Sophie Bryant was an Anglo-Irish mathematician, feminist, suffragist, teacher, and promoter of moral education. She played a key role in […]