I remain an agnostic, and the practical outcome of agnosticism is that you act as though God did not exist.

W. Somerset Maugham, The Summing Up (1938)

W. Somerset Maugham was a playwright, novelist, and short story writer, best remembered today for works such as Of Human Bondage (1915) and Cakes and Ale (1930). Maugham was also a humanist, who expressed this lived philosophy in his literary works, memoirs, and affiliation to the Rationalist Press Association.

The belief in God is not a matter of common sense, or logic, or argument, but of feeling. It is as impossible to prove the existence of God as to disprove it. I do not believe in God. I see no need of such an idea. It is incredible to me that there should be an after-life. I find the notion of future punishment outrageous and of future reward extravagant. I am convinced that when I die, I shall cease entirely to live; I shall return to the earth I came from.

W. Somerset Maugham, A Writer’s Notebook (1949)

Born in Paris to English parents, William Somerset Maugham was orphaned at a young age and sent to live with his uncle, a vicar, in England. Though he qualified as a doctor in 1897, Maugham never practised medicine, turning decisively to writing following the encouraging success of his first novel Liza of Lambeth, published that year.

His experiences as a young man, including his medical training and intelligence work during the First World War, greatly influenced both his writings and his worldview. His own attitude to this was a distinctly humanist one: ‘if you want to get any benefit from such an experience you must have an open mind and an interest in human beings’. Of his medical training’s impact on his personal beliefs, Maugham wrote:

…becoming a medical student, I entered a new world. I read a great many books. They told me that man was a machine subject to mechanical laws; and when the machine ran down that was the end of him. I saw men die at the hospital and my startled sensibilities confirmed what my books had taught me. I was satisfied to believe that religion and the idea of God were constructions that the human race had evolved as a convenience for living, and represented something that had at one time, and for all I was prepared to say still had, value for the survival of the species, but that must be historically explained and corresponded to nothing real. I called myself an agnostic, but in my blood and my bones I looked upon God as a hypothesis that a reasonable man must reject.

W. Somerset Maugham, The Summing Up (1938)

Maugham viewed this not as loss but as liberation. When ‘I ceased to believe in God, he wrote, ‘I felt the exhilaration of a new freedom’.

Critical success came for Maugham with his novel Of Human Bondage (1915), a semi-autobiographical work that explored themes of love, art, and the struggle for personal fulfilment. His writing style was characterised by clarity, precision, and a keen observation of human behaviour, and Of Human Bondage was followed by The Moon and Sixpence (1919), The Painted Veil (1925), and Cakes and Ale (1930). Maugham’s writings inspired numerous film and television adaptations, including Alfred Hitchcock’s The Secret Agent (1936), derived from one of Maugham’s short stories.

Maugham married Syrie Wellcome (née Barnardo) in 1917, though the couple divorced in 1929 following an unhappy union. His most enduring relationship was with Gerald Haxton, an Anglo-American Maugham had met in London before the First World War, and with whom he ultimately set up home in France.

An Honorary Associate of the Rationalist Press Association, Maugham was firm and open in his rejection of religion. In A Writer’s Notebook, he wrote: ‘I’m glad I don’t believe in God. When I look at the misery of the world and its bitterness I think that no belief can be more ignoble’. But his positive humanism came through in his belief in ‘loving-kindness’: a human capacity which gave meaning and warmth to life. In The Summing Up, a literary memoir first published in 1938, Maugham wrote:

Loving-kindness is the better part of goodness. It lends grace to the sterner qualities of which this consists and makes it a little less difficult to practice those minor virtues of self-control and self restraint, patience, discipline and tolerance, which are the passive and not very exhilarating elements of goodness. Goodness is the only value that seems in this world of appearances to have any claim to be an end in itself. Virtue is its own reward. I am ashamed to have reached so commonplace a conclusion… I have gone a long way round to discover what everyone knew already.

It may be that in goodness we may see, not a reason for life nor an explanation of it, but an extenuation. In this indifferent universe, with its inevitable evils that surround us from the cradle to the grave, it may serve, not as a challenge or a reply, but as an affirmation of our own independence. It is the retort that humour makes to the tragic absurdity of fate. Unlike beauty, it can be perfect without being tedious, and, greater than love, time does not wither its delight.

Maugham died in Nice on 15 December 1965, at the age of 91, and was cremated five days later in Marseilles. He is remembered today as a gifted and successful writer, as well as a cornerstone of the humanist literary tradition.

The value of culture is its effect on character. It avails nothing unless it ennobles and strengthens that. Its use is for life.

W. Somerset Maugham, The Summing Up (1938)

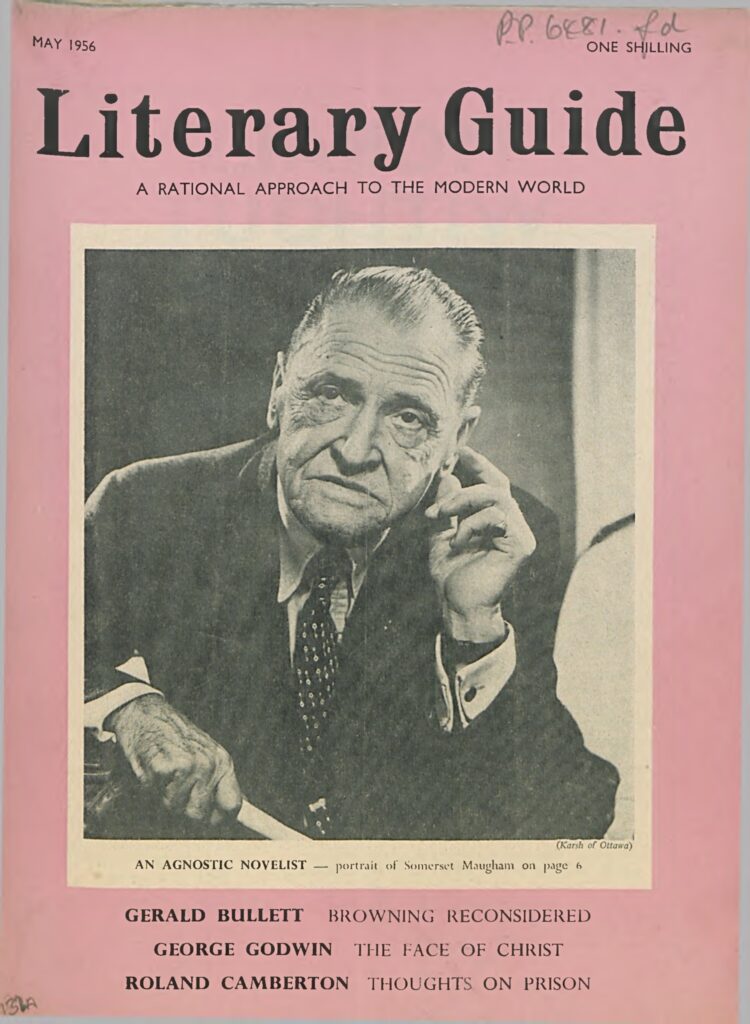

Maugham’s humanism is reflected in his literary works, his memoirs, and his personal affiliations. In literature, he explored the diverse and complex nature of human beings, and in his personal philosophy displayed an unflinching rationalism, rooted in humanity’s capacity for ‘loving-kindness’. In the words of one writer in the Literary Guide (now New Humanist) in 1956:

He has straitly kept the greatest of all self-commandments: To be oneself and to do one’s work. He conceived a pattern of life, a true pattern valid for himself, and faithfully fulfilled it. Can any one of us do more?

C. G. L. Du Cann, ‘An Agnostic Novelist’ in the Literary Guide, May 1956

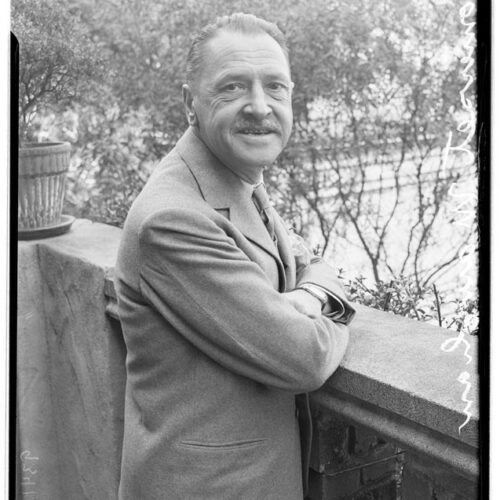

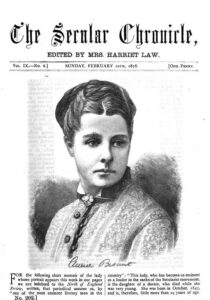

Main image: W. Somerset Maugham by Samuel M. Crow. Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. This work is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license

The object of Secularism is the promotion of human happiness in this world… [The Secularist] believes the surest way of […]

I might fill columns with tales of the debaters, co-operators, socialists, individualists, critics, artists, scientists, clergy and cranks, who, as […]

Humanism is a way to live, to give meaning to life and to find an understanding of our place in […]

We desire to attract men and women holding all shades of opinion, but having in common a conviction that morality […]