Wales has long been a nation of nonconformists, with a history of challenging the power and influence of the established church. Evidence of the humanist approach can be seen in a rich tradition of freethinking, including efforts for social and political reform rooted in rational thinking and secularist ideals.

During the 18th century, Wales was home to influential deists, including Thomas Morgan (d. 1743) and David Williams (1738–1816): freethinkers who challenged the claims of revealed religion. Over the course of the 19th century, humanist ideas underpinned movements like chartism, Owenism, and the Ethical movement, each of which had an active presence in Wales. Indeed, philanthropist and reformer Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Powys, and is buried there. The 20th century – especially after the First World War – saw the rise of secularism, a drop-off in people attending church, and the growth of organised humanist groups. Today, 50% of people in Wales describe themselves as having ‘no religion’, and many of these hold humanist values.

Before the coming of Christianity during the 1st century CE, Wales, like other parts of the British Isles, was home to a variety of different religious beliefs. Evidence for these includes ceremonial burials, and stone structures and circles, whose meanings we can only make theories about. When the Romans invaded Britain in 43 CE, they combined their own gods with native ones. As long as it didn’t threaten the power of the Romans, people seem to have been allowed to continue following their own traditions. By the end of the 4th century, however, Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire. Like in England, Ireland, and Scotland, the power of Christian rule made expressing humanist ideas or challenging religion dangerous for many hundreds of years.

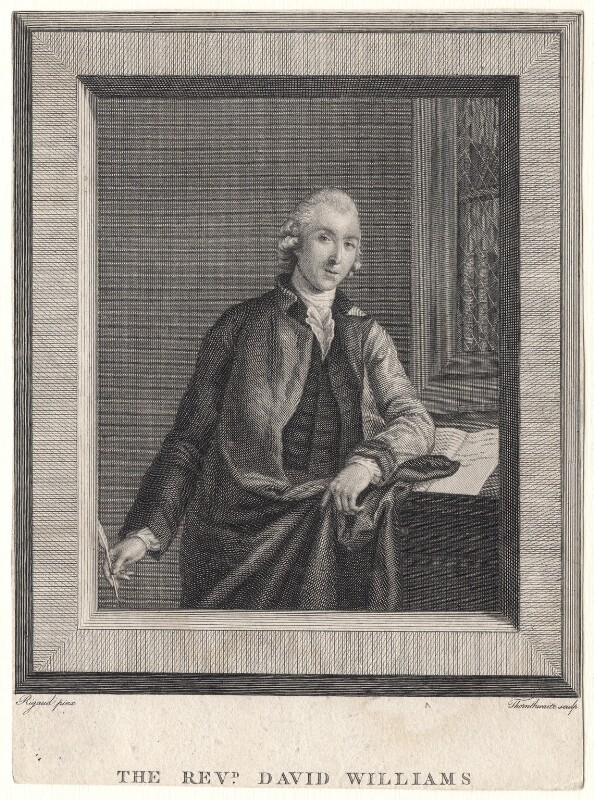

The period of history known as the Enlightenment (or sometimes the Age of Reason) began in the 17th century, and saw a new faith in human reason to discover natural laws and human rights. During this time, ideas like deism emerged. Deists believed that truth could be discovered through reason and rational enquiry, and challenged the authority of the Bible. Influential deists Thomas Morgan (d. 1743) and David Williams (1738–1816) were both of Welsh origin. David Williams moved to London and established a school there. He described his deist ideas as a ‘religion of nature’, which he hoped could bring all people together while allowing them to think for themselves. Above all, Williams believed in every individual’s right to form their own ideas, and to follow their conscience in matters of religious belief.

The 1700s also saw the birth, in Newtown, of Robert Owen (1771-1858), whose ideas would inspire a movement based on cooperation and social improvement – focusing on what human beings could do to make the world better, without relying on any god to help them. Owen’s reformist ideals were rooted in a belief that human beings were shaped by their environment, not born destined to be either moral or criminal; rich or poor.

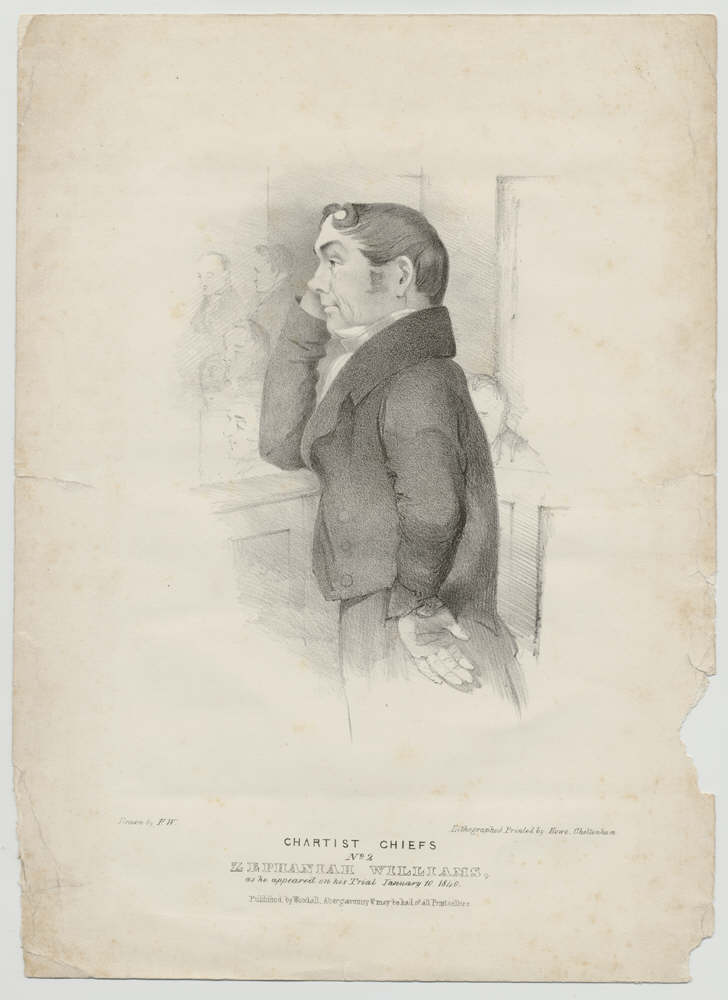

Others in Wales, like Zephaniah Williams (c. 1795–1874), were chartists, who took their name from the ‘people’s charter’ they drew up. Chartists wanted all adult men to have the vote, believing that without it their power to influence change and improve their own working and living conditions was limited. Zephaniah Williams, like Robert Owen, was a freethinker, and both believed that it was in the hands of human beings to bring about social change and improvement. In 1831, John Thomas (later the editor of Wales’ first working class newspaper) formed the Free Enquirers, a group who supported the freethinking ideas of radical publisher Richard Carlile in London.

In a letter to Reverend Benjamin Williams, Zephaniah Williams defended the rationalist standpoint and the virtue of freethinkers. He wrote:

I would advise all men to take nothing upon trust, but all upon trial; whether in politics, religion, Ethics, or any thing else: to set down with a determined resolution; to examine closely; and to be directed by that which reason most approves.

Zephaniah Williams, letter to Benjamin Williams (1831)

For his part in chartist uprisings, Zephaniah Williams was initially sentenced to death, but later transported to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), Australia to serve his punishment.

The 19th century also witnessed a number of other efforts to challenge the authority of the established Church in Wales. Launched in 1840, Welsh chartist magazine Udgorn Cymru (The Trumpet of Wales) condemned the payment of church tithes and advocated the disestablishment of the Anglican Church. The work for disestablishment was later taken up by The Liberation Society (founded in 1844 as the British Anti-State Church Association). The Society campaigned against state involvement in religious matters and religious involvement in matters of the state, emphasising the importance of freedom of conscience.

In 1886, the Anti-Tithe League was established, later becoming The Welsh Land, Commercial and Labour League. The League sought land reform and the disestablishment of the Church – causes linked by the unfair power wielded by wealthy English and Anglican landowners over people in Wales. Efforts for disestablishment united nonconformists, secularists, and the non-religious, who collectively rejected the undue influence of the Church.

Though the Ethical movement began in England during the 1880s, Wales’ first ethical societies appear to have been established from the mid-1890s. From the first decade of the 20th century, Aberdare, Cardiff, and Merthyr each had an ethical society, emphasising living well without reference to supernatural ideas.

The 1914 Welsh Church Act enabled the disestablishment of the Church of England in Wales, and the creation of an independent Church in Wales – but one separate from the state. This was something many non-religious people had campaigned for, alongside others who disagreed with the Church of England having special privileges in Wales. Because of the First World War, the Act did not take effect until 31 March 1920.

During the 20th century, Welsh humanists played important roles in the arts, science, politics, and education on a national and international scale. One, Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan (1897-1960), oversaw the creation of the National Health Service (NHS) – which made healthcare free to all who needed it. As his wife, Jennie Lee, said: ‘He was a great humanist whose religion lay in loving his fellow men and trying to serve them’.

As was the case elsewhere in the UK, from the 1960s humanist groups sprang up across Wales – some taking over from earlier ethical societies, and some emerging anew. One of the earliest was the Humanist Society at the University College of North Wales, for which philosopher Rupert Crawshay-Williams delivered the inaugural lecture.

The Senedd was the first UK nation’s government to be created on secular ideals. Unlike the parliament in Westminster, Senedd meetings have no Anglican prayers as part of their business, and no member is privileged or disadvantaged because of their religion or beliefs. The Senedd’s secular basis also has an important effect on the way decisions are made and laws are passed: based on evidence and human rights, and recognising the many different religions and beliefs present in Wales today.

Rhodri Morgan, who became First Minister of Wales in 2000, was a humanist. When he died in 2017, his was the first public humanist funeral in the United Kingdom.

Today, Wales is the most non-religious country in the UK, with more people identifying as non-religious than Christian. Wales Humanists aim to work with the Welsh Government and people of goodwill from all backgrounds to achieve a situation where everyone in Wales is treated equally, regardless of religion or belief.

Equality and Diversity Statistics | Welsh Government

Humanist Heritage for Welsh schools | Understanding Humanism

There is nothing in this world to compare with the joy of finding something to do that one believes to […]

The attempt to create communities where men and women alike share the full stature of humanity is an attempt to […]

We are (of all the synonyms I most prefer to ‘humanist’) freethinkers. We are deprived of nothing. We have lost […]

No creative thinker has so governed… my mind as the French genius who framed the maxim – “Love for principle, […]