Our interest, it seems to me, lies with so much of the past as may serve to guide our actions in the present, and… with so much of the future as we may hope will be appreciably affected by our good actions now. Beyond that, as it seems to me, we do not know, and we ought not to care. Do I seem to say, “Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die?” Far from it; on the contrary, I say, “Let us take hands and help, for this day we are alive together.”

William Kingdon Clifford, ‘The First and the Last Catastrophe’ in Popular Science Monthly (July 1875)

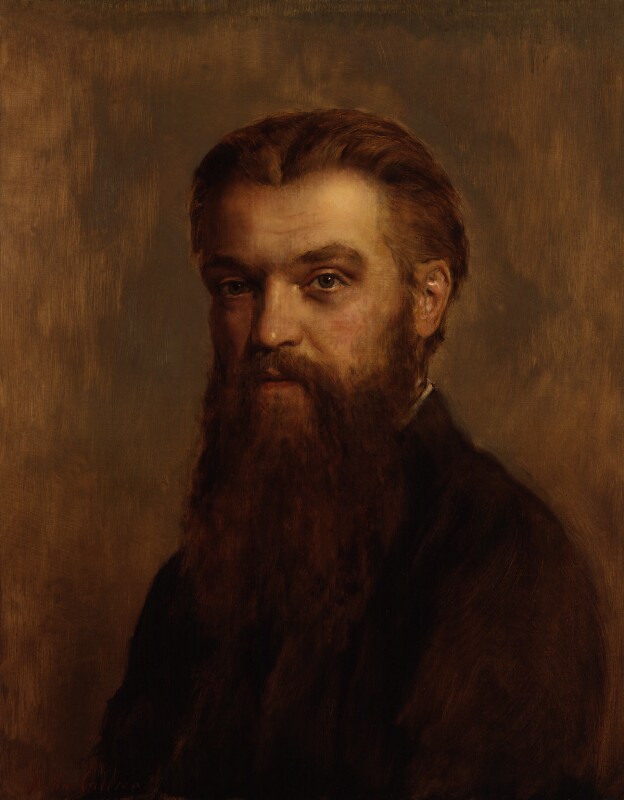

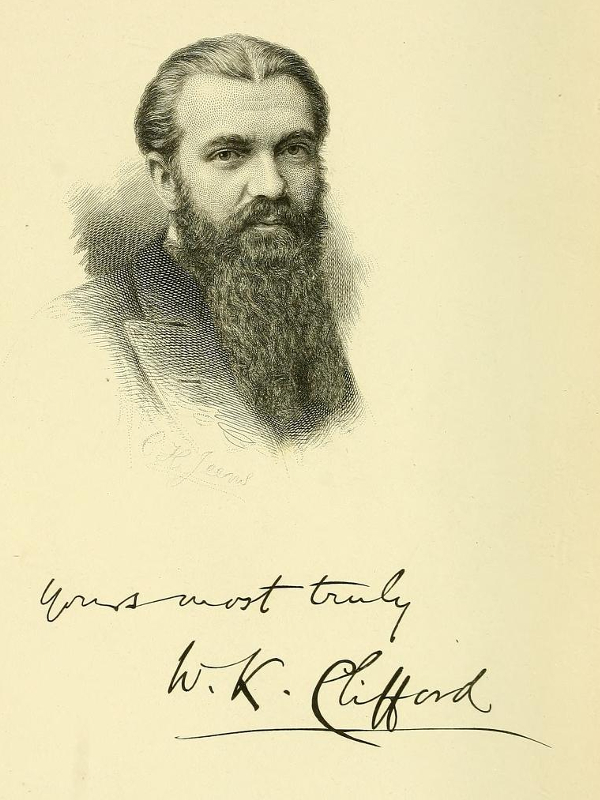

William Kingdon Clifford was a mathematician, philosopher, and consummate humanist, who was a bold Victorian proponent of ethics without religion. A close friend of many other prominent freethinkers of the period, including Moncure Conway, T.H. Huxley, and Leslie Stephen, in just 33 years of life Clifford’s impact was large. Casting off the Christianity of his youth, Clifford embraced and expounded an inspiring humanist philosophy, rooted in reason, empathy, the pursuit of truth, and a wholehearted love of life.

When he was at Cambridge he was an ardent High Churchman, but from that creed he speedily broke away to become the enthusiastic propounder and defender of the faith as it is in Darwin. Nihil quod tetigit non ornavit [He touched nothing without embellishing it] — whether it was in lecturing on ethics or atoms, while his joyous nature revelled in writing fairy tales and songs for children, to whom he was devoted.

Edward Clodd, Memories (1916)

William Kingdon Clifford was born in Exeter on 4 May 1845, and raised by his father in the strict Anglicanism he would later shed completely. Following early private schooling, at just 15 he went up to King’s College, London and from there won a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. At Cambridge, he continued to excel, and was elected a member of the secretive Conversazione Society (better known as the Apostles). Clifford also read widely in works by scientific freethinkers like Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer, and Spinoza, ushering him ever further away from the religiosity of his early years.

At university, and for the remainder of his life, Clifford was noted for his twin embrace of the sciences and the humanities, and for his profound skill in communicating complex ideas with clarity and enthusiasm. His close friend from Cambridge, Frederick Pollock, described ‘the winning felicity of his manner, the varied and flexible play of his thought, the almost boundless range of his human interests and sympathies’. Elected a fellow of Trinity College in 1868, he became a well known and popular speaker on diverse subjects. In a lecture given that year, Clifford stated the belief in intellectual openness which underpinned his personal philosophy: ‘A mind that would grow,’ he argued, ‘must maintain an attitude of absolute receptivity; admitting all, being modified by all, but permanently biased by none’.

In 1871, he took up a professorship in applied mathematics at UCL, known as the godless college of Gower Street and, in 1875 – leaving a chalked note on the blackboard explaining his absence to students – married Lucy Jane Lane, with whom he would have two daughters. Among the letters of congratulation received was one from George Henry Lewes and his partner George Eliot (by then living together as Mr and Mrs Lewes), hoping that Lucy might be ‘the central happiness and motive force’ of Clifford’s life and career. Indeed, the couple became known for the vibrant salons at their home, which were remembered fondly by all of those who attended. Friend and fellow freethinker Edward Clodd recalled those ‘Sunday afternoons at Colville Road’ as ‘linked with fragrant and refreshing memories’. There, Clodd wrote:

You were sure to meet some one worth the knowing… a company of sane and healthy men and women, gentle and simple, who wanted to meet one another and have a full, free talk which was “gay without frivolity.” Old friends — Sir Frederick Pollock, the Huxleys and Colliers, Sir Leslie Stephen and G. J. Romanes — were often there. More rarely, Cotter Morison, York Powell, Mark Pattison, Grant and Nellie Allen, Thomas Hardy, and Mrs. Lynn Linton dropped in; with these and others there was never a barren time.

Edward Clodd, Memories (1916)

This enjoyment of discussion and discovery was central to Clifford’s academic as well as personal life. Pollock wrote that the ‘pursuit of knowledge for its own sake… was the leading character of Clifford’s work… The discovery of truth was for him an end in itself, and the proclamation of it, or of whatever seemed to lead to it, a duty of primary and paramount obligation’. One of Clifford’s best known quotes, taken from ‘The Ethics of Belief’ (1877), summed up this devotion to the scientific method, stating: ‘It is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence’. Although Clifford became recognised as a kind of ‘preacher’ in the scientific spirit of Darwin, Huxley, and John Tyndall, Pollock was at pains to note that ‘he never seemed to be imposing dogmas on his hearers, but to be leading them into the enjoyment of a common possession’. An enduringly popular teacher and lecturer, Clifford ‘did not tell them that knowledge was priceless and truth beautiful; he made them feel it’.

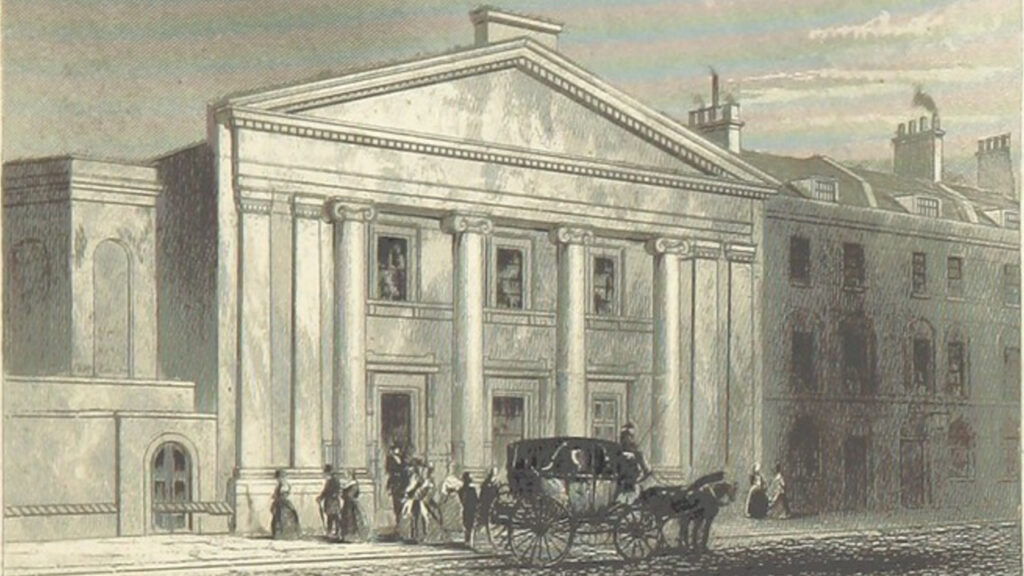

With Moncure Conway, and encouraged by T.H. Huxley, Clifford was instrumental in organising the 1878 Congress of Liberal Thinkers. The Congress took place over two days at South Place, and the association formed from it had among their aims:

Huxley, who became President of the Congress, remarked with satisfaction that such an eminent membership – which included delegates from the UK, Europe, America, and India – proved ‘Freethinkers are no longer to be simply bullied’.

Despite being central to its realisation, Clifford’s fragile health left him unable to attend the Congress that June. He had long been troubled by pulmonary illness and had, at various times, sought comfort in warmer climates. This he did in 1878, and though he returned to England in August that year, he remained ill, sailing again for Madeira with Lucy in February 1879. Friends including Huxley and Tyndall, ‘in public recognition of his great scientific and literary attainments,’ launched a fund to support him. Pollock would later write that ‘Clifford’s patience, cheerfulness, unselfishness, and continued interest in his friends and in what was going on in the world, were unbroken and unabated through all that heavy time’.

William Kingdon Clifford died from tuberculosis in Madeira on 3 March 1879, aged just 33. An epitaph of Clifford’s creation on his gravestone in Highgate Cemetery reads:

I was not, and was conceived: I loved, and did a little work: I am not, and grieve not.

Following his death, Frederick Pollock and Leslie Stephen edited Clifford’s Lectures and Essays, to which Pollock contributed an introduction. In this, the philosophy of Clifford’s life, as illuminated by his death, was unequivocally stated:

Far be it from me, as it was far from him, to grudge to any man or woman the hope or comfort that may be found in sincere expectation of a better life to come. But let this be set down and remembered, plainly and openly, for the instruction and rebuke of those who fancy that their dogmas have a monopoly of happiness, and will not face the fact that there are true men, ay and women, to whom the dignity of manhood and the fellowship of this life, undazzled by the magic of any revelation, unholpen of any promises holding out aught as higher or more enduring than the fruition of human love and the fulfilment of human duties, are sufficient to bear the weight of both life and death. Here was a man who utterly dismissed from his thoughts, as being unprofitable or worse, all speculations on a future or unseen world; a man to whom life was holy and precious, a thing not to be despised, but to be used with joyfulness; a soul full of life and light, ever longing for activity, ever counting what was achieved as not worthy to be reckoned in comparison of what was left to do. And this is the witness of his ending; that as never man loved life more, so never man feared death less.

And this is the witness of his ending; that as never man loved life more, so never man feared death less.

Frederick Pollock, Introduction to Lectures and Essays of the Late William Kingdon Clifford (1879)

Throughout his life, Clifford exemplified a humanist philosophy which continues to resonate today, and influenced many during his lifetime. Openness to doubt, allied with a devoted pursuit of truth, underpinned his work, and he firmly believed that any philosophical speculation on ethics should also be practical, and geared towards the greater wellbeing of society. These are values which were also at the heart of the Ethical movement, which gave rise to organised humanism in the UK. Clifford advocated for the supremacy of scientific reasoning over dogmatic religion, and argued the need for absolute freedom in the discussion of both – a cause taken up by many humanists who followed him. He was also a much loved husband and friend, whose personal charm was as significant as his noted intellect. As Pollock concluded in his recollections, ‘the real expression of Clifford’s varied and fascinating qualities was in his whole daily life and conversation, perceived and felt at every moment in his words and looks, and for that very reason impossible to describe’. His wife Lucy, approached for an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography in 1913 said: ‘There was nothing that he couldn’t have done or wouldn’t have done if he had lived, for there was no side of life that did not appeal to him’.

Lectures and Essays of the Late William Kingdon Clifford (1879; 1886) | The Internet Archive

William Kingdon Clifford, ‘The First and the Last Catastrophe’ (1875)

Timothy J. Madigan, ‘W.K. Clifford: Life and Philosophy’ (2009) | The Ethical Record

Edward Clodd, Memories (1916) | The Internet Archive

Moncure Conway, Autobiography Vol II (1904) | The Internet Archive

William Kingdon Clifford | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Rationalism is… primarily a mental attitude, not a creed or a definite body of negative conclusions. No uniformity of opinions […]

On 11 November 1849, at the Literary and Scientific Institution, 23 John Street (now Whitfield Street), London, George Jacob Holyoake […]

In my experience he was the kindest of men, far too modest about his own contributions and always prepared to […]

Good writing excites me, and makes life worth living. Harold Pinter Harold Pinter was one of the 20th century’s most […]