…for Shakespeare, in the matter of religion, the choice lay between Christianity and nothing. He chose nothing; he chose to leave his heroes and himself in the presence of life and of death with no other philosophy than that which the profane world can suggest and understand.

George Santayana, ‘The Absence of Religion in Shakespeare’ in Interpretations of Poetry and Religion (1900)

Widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language, William Shakespeare’s poems and plays have inspired people across the world for centuries. While the age in which he lived was dominated by religious doctrine, Shakespeare’s works were rooted in worldly affairs, secular concerns, and the intricacies of human character. This enduring focus on the human condition, largely independent of divine intervention, endears his vast body of work to humanists and religious people alike, while his own beliefs have been the subject of significant debate.

William Shakespeare was born in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, and baptised on 26 April 1564. His father, John Shakespeare, was a glove-maker and alderman, and his mother, Mary Arden, came from a local landowning family. William likely attended the King’s New School in Stratford, receiving a classical education focused on Latin. Aged 18, Shakespeare married Anne Hathaway, eight years his senior, and the couple had three children: Susanna, and twins Hamnet and Judith. Hamnet died aged 11. Little is known about Shakespeare’s life between 1585 and 1592 – known as the ‘lost years’ – but by the early 1590s, he was established in London as an actor and playwright.

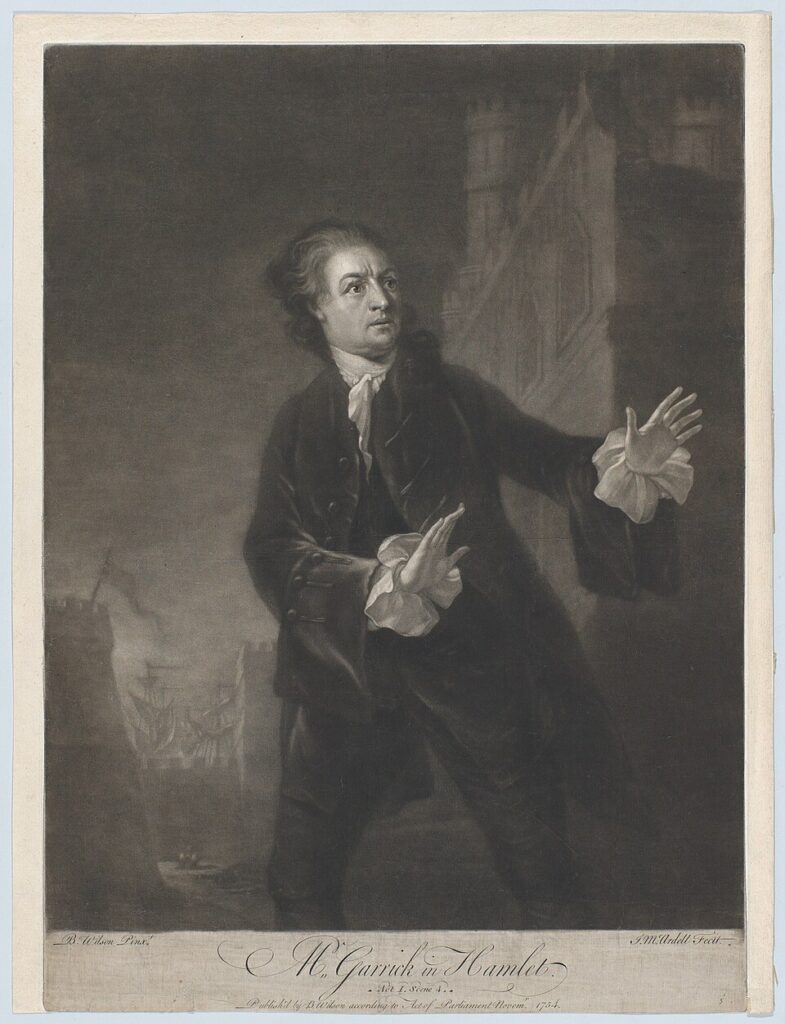

Shakespeare became a leading member of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men (later the King’s Men), a successful acting company, for whom he was the principal playwright. He was also a part-owner of the Globe Theatre. Over roughly two decades, he wrote around 39 plays – comedies, histories, tragedies, and romances – as well as 154 sonnets and narrative poems. His works, including masterpieces like Hamlet, King Lear, Othello, Macbeth, and Romeo and Juliet, explored a vast array of themes and introduced more than 1700 words into the English language.

Shakespeare prospered, ultimately buying a large house in Stratford, where he appears to have retired around 1613. He died on 23 April 1616, and was buried in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. Throughout his life, Shakespeare and his family outwardly conformed to the established Church of England, as evidenced by parish records of baptisms, marriages, and burials.

Despite his formal adherence to the Church of England, the nature of Shakespeare’s personal religious beliefs remains the subject of extensive debate, with scholars variously proposing he was a conforming Anglican, a secret Catholic, a sceptic, or even an atheist. What is less disputed is the predominantly secular focus of his plays. Unlike many contemporaries, his works rarely centre on explicitly religious themes or dogma. Instead, they delve into human ambition, love, jealousy, revenge, political power, and the moral dilemmas faced by individuals.

The morality of Shakespeare’s later tragedies is not religious in the ordinary sense, and certainly is not Christian. Only two of them, Hamlet and Othello, are supposedly occurring inside the Christian era, and even in those, apart from the antics of the ghost in Hamlet, there is no indication of a ‘next world’ where everything is to be put right. All of these tragedies start out with the humanist assumption that life, although full of sorrow, is worth living, and that Man is a noble animal…

George Orwell, ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’, 1947

Characters in Shakespeare’s plays often make choices based on human motivations and face earthly consequences, rather than primarily divine judgment. Famous lines, such as Polonius’ advice ‘To thine own self be true’ (Hamlet) or Edmund’s dismissal of astrological determinism in King Lear (‘we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and stars, as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion’) can be interpreted as reflecting a humanist emphasis on individual responsibility and agency. For this reason, the words ‘to thine own self be true’ adorn the space above the stage at Conway Hall: a testament to freedom of thought and the right to self-determination.

Hamlet contains other very humanist reflections on the human condition too, exploring our potential and our material nature:

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculties! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals! And yet to me what is this quintessence of dust?

Hamlet in The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act II, Scene II

Elsewhere in Shakespeare’s works, while characters may refer to ‘a divinity that shapes our ends’ or fear ‘the Everlasting’, the plays often explore the complexities of life and death without recourse to promised salvation or damnation, portraying a world where human actions – and lived consequences in the here and now – are paramount. Macbeth shows the dangers of allowing superstition and prophecy to override moral judgement, and the capacity to choose our own destiny – something Romeo and Juliet do (choosing self-determination over authority and tradition), although with undesirable consequences.

Writing at the end of the 19th century, Spanish-American philosopher and writer George Santayana noted in his essay ‘The Absence of Religion in Shakespeare’ that the playwright ‘chose to leave his heroes and himself in the presence of life and death with no other philosophy than that which the profane world can suggest and understand’. The essay’s opening paragraph claimed:

We are accustomed to think of the universality of Shakespeare as not the least of his glories. No other poet has given so many-sided an expression to human nature, or rendered so many passions and moods with such an appropriate variety of style, sentiment, and accent. If, therefore, we were asked to select one monument of human civilisation that should survive to some future age, or be transported to another planet to bear witness to the inhabitants there of what we have been upon earth, we should probably choose the works of Shakespeare. In them we recognise the truest portrait and best memorial of man. Yet the archaeologists of that future age, or the cosmographers of that other part of the heavens, after conscientious study of our Shakespearian autobiography, would misconceive our life in one important respect. They would hardly understand that man had had a religion.

George Orwell, in a 1947 essay, wrote: ‘We do not know a great deal about Shakespeare’s religious beliefs, and from the evidence of his writings it would be difficult to prove that he had any.’ In the years since, many others have continued the discussion. Dan Falk, author of The Science of Shakespeare: a New Look at the Playwright’s Universe (2014) has written:

The canon offers other hints of a godless Shakespeare: Hamlet’s obsessive contemplation of death and decay, with no mention of an afterlife; Helena’s assertion in All’s Well That Ends Well that “Our remedies oft in ourselves do lie/ Which we ascribe to heaven”; Macbeth’s assertion that life is “a tale, told by an idiot, signifying nothing.” None of this proves that Shakespeare was an atheist—but it at least shows that he could imagine a godless world.

Dan Falk, ‘Much Ado About Nothingness Was Shakespeare an atheist? Or more of a secular humanist?’, Slate, 23 April 2014

Shakespeare was born during years when the word ‘atheist’ was just entering the English language: a derogatory term to describe those who didn’t believe in, or disregarded, gods. As writers from Santayana to Falk have suggested, Shakespeare could certainly conceive of a godless world, but one with no less beauty, complexity, or morality than one ruled by divine forces.

We are such stuff

Prospero in The Tempest, Act IV, Scene I

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded by a sleep.

While it is anachronistic to label Shakespeare a ‘humanist’ in the modern sense, his expansive and often secular investigation into what it means to be human – and human alongside others – gives his work enduring power. His plays provide a vast canvas for exploring ethics, psychology, and social structures from a perspective grounded in human experience, and are a testament to the profound creativity of human beings.

Shakespeare | Humanists UK

Shakespedia | Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

George Santayana, ‘The Absence of Religion in Shakespeare’ in Interpretations of Poetry and Religion (1900)

George Orwell, ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’ (1947)

Man for man in larger sense does what heaven fails to do. Sara A. Underwood, quoted by Rufus K. Noyes […]

To those who regard the furtherance of International Good Will and Peace as the highest of all human interests, the […]

Julia Huxley was a feminist and freethinker, who profoundly influenced a generation of girls who attended the school she founded […]

Harry Stopes-Roe was one of the most tireless and dedicated humanist campaigners of the 20th century. Son of the influential […]