Man for man in larger sense does what heaven fails to do.

Sara A. Underwood, quoted by Rufus K. Noyes in Views of Religion (1906)

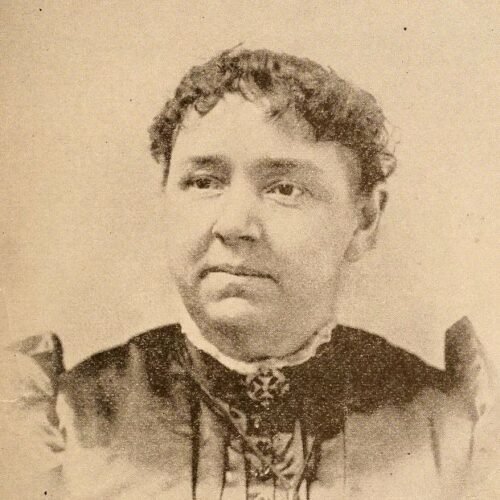

Sara A. Underwood was a prominent freethought lecturer, writer, editor, and suffragist. Her 1876 work, Heroines of Freethought, celebrated women freethinkers from Mary Wollstonecraft to George Eliot: those ‘strong enough of heart and brain to understand and accept Liberal truths, and brave enough to avow publicly [their] faith in the “belief of the unbelievers.”’ Through her knowledge of, and admiration for, women like these, Underwood strengthened her case for suffrage, using the achievements of others to challenge claims of women’s unsuitedness to political involvement. A remarkable humanist herself, Underwood made a significant contribution to reviving the reputations of others like her.

Sara A. Underwood was born Sara A. Francis in Penrith, Cumbria, moving with her family to Rhode Island while still a young child. A later profile in The Free Thought Magazine described her as being ‘brought up in the Christian faith of the most orthodox type’ but notes:

… she was a thinker, a questioner, an omnivorous reader, and at the age of twenty, although she had never read a line of a Freethought work, she was decidedly skeptical as to the supernatural part of Christianity.

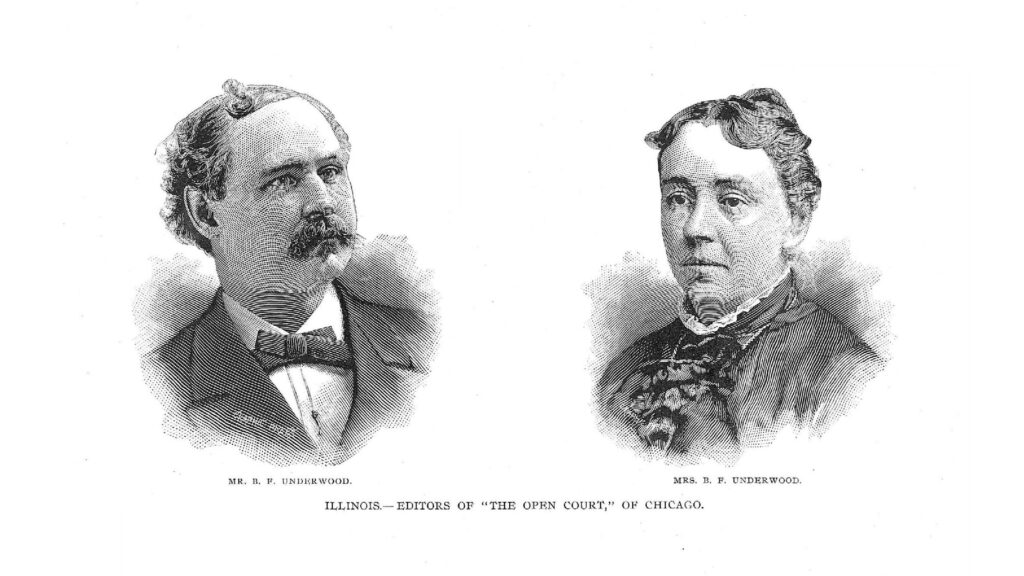

Sara Francis married Benjamin Franklin Underwood on 6 September 1862, the partnership ‘a union of kindred minds as well as hearts’. Over the following decades, both Underwoods became well-known figures in freethinking circles and on the lecture circuit, as well as co-editors of freethought journals. Underwood wrote poetry and prose, and also contributed articles to publications including the Investigator, The Revolution, The Evolution, Woman’s Standard, The North American Review, and The New England Magazine.

In 1876, Underwood published Heroines of Freethought, celebrating the lives of: Madame Roland, Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, George Sand, Harriet Martineau, Frances Wright, Emma Martin, Margaret Chappellsmith, Ernestine Rose, Frances Power Cobbe, and George Eliot. While acknowledging the many other women throughout history who had ‘succeeded in throwing aside creeds and all sectarianism’, Underwood selected these subjects on account of the ‘thorough Radicalism of the views they held’. She wrote:

I have contented myself with sketching these few central female figures in the history of Radical Religion. And my only hope in grouping them thus together is to win for them, from those to whom they are comparatively unknown, save as names only, a little of the admiration and respect which I myself have ever felt for them because of the dignity and moral heroism of their lives.

Between 1880 and 1886 Sara Underwood assisted her husband as co-editor of the Boston Index, the organ of the Free Religious Association. Contributors to the Index included Felix Adler, George Jacob Holyoake, and the Underwoods themselves. Charles Darwin subscribed from 1871 until his death in 1882.

Towards the end of the 1880s, the couple moved to Chicago to serve as editor and manager (Benjamin) and associate editor (Sara) of the journal The Open Court. A notice in The Graphic News contained a ringing endorsement of the couple from Boston journalist Lilian Whiting, who wrote:

In welcoming Mr. and Mrs. Underwood to Chicago, your city will gain citizens whose intellectual power, whose sympathetic interest in every vital subject, whose goodness of heart and simplicity and dignity of character render them active social forces. There are lives which radiate energy and enthusiasm for all that is noble and true and of good report, and among the most eminent of such lives in Boston are a group, out of which could be named Mr. and Mrs. B. F. Underwood.

The Open Court (which Sara Underwood named) was ‘devoted to the work of establishing ethics and religion upon a scientific basis,’ and included contributions from a vast range of prominent thinkers. Among these were many leading figures in the Ethical movement, such as Moncure Conway, Mary Sophia Gilliland, William Mackintire Salter, and Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner. The journal’s aims were rationalist and humanist:

The Open Court, while advocating morals and rational religious thought on the firm basis of Science, will aim to substitute for unquestioning credulity intelligent inquiry, for blind faith rational religious views, for unreasoning bigotry a liberal spirit, for sectarianism a broad and generous humanitarianism.

While in Boston, Underwood had been Treasurer of the National Woman Suffrage Association of Massachusetts. In Chicago, she continued to write and organise for the cause of women’s suffrage. In the pages of The Open Court, typically writing as ‘S.A.U.’, Underwood remained a powerful advocate of both feminism and freethought. In one 1887 article, she rebuked those who used the Bible in arguments either for or against women’s suffrage:

Neither the Bible nor the Constitution of the United States can be authority in the matter of woman suffrage, a question which at the time they were written had no raison d’être. In the moral and intellectual evolution of mankind “new occasions” will forever “teach new duties,” and no generation, however noble or advanced, can frame immutable laws for a generation yet unborn, since the environments and needs of that people can be understood and provided for only, or best, by themselves.

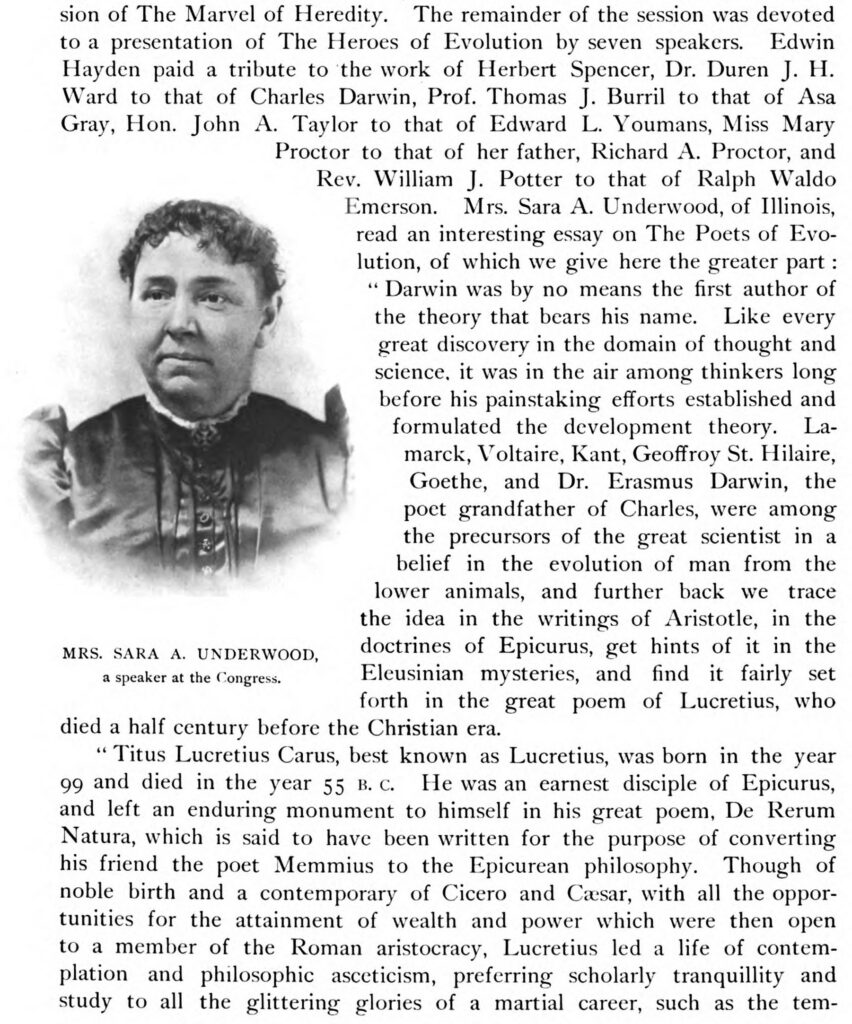

A firm advocate of evolutionary theory, Underwood was a speaker at the Congress of Evolutionists, part of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. She presented a paper on ‘The Poets of Evolution’, which included discussions of Lucretius and Epicurus, as well Voltaire, Kant, Goethe, and Erasmus and Charles Darwin.

The Underwoods moved to Quincy, Illinois in 1897, but Sara’s health was failing. Although she lived a quiet life in retirement, her obituary in the Quincy Journal stated that those who knew her in these years ‘admired her for her intellectual ability, her large knowledge of literature, and her sterling moral worth.’ Sara A. Underwood died in a sanatorium in Jacksonville, Illinois in the early hours of 16 March 1911.

Through her own example, and in her championing of other freethinkers, Sara A. Underwood did much to further the cause of rationalism and freethought during the latter half of the 19th century. She provides a fascinating glimpse into the life of a politically engaged, freethinking woman in the United States during that period, and of a transatlantic network of humanist thinkers. Like other near contemporaries – including Zona Vallance and Lady Florence Dixie – Underwood drew on evolutionary science and scientific advances to bolster arguments for women’s suffrage and equality. And clearly, through her involvement with the journals she edited and wrote for, she was known to the leading secularists and humanists in her native country. Heroines of Freethought provides a concrete example of a freethinking woman using those who came before her to strengthen the reputation of other agnostic women. This included demonstrating the compassionate ideals and remarkable reformism of women who had embraced a humanist outlook, alongside whom Sara A. Underwood very much deserves to be remembered.

Heroines of Freethought by Sara A. Underwood (1876)

Online archives of The Open Court (1887-1936)

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

The National Secular Society is a campaigning organisation, founded in 1866 to champion the principles of secularism and the separation […]

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

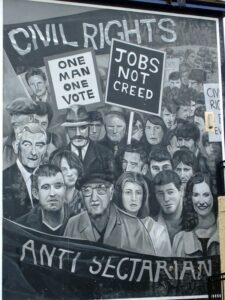

A brief history of humanism and secularism in Northern Ireland Organised humanism began in Northern Ireland in the 19th century, […]