All moral and political wisdom should tend mainly to this, the just distribution of the physical means of happiness.

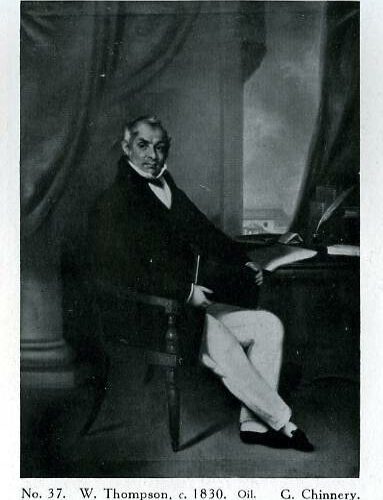

William Thompson, An Inquiry into the Principles of the Distribution of Wealth Most Conducive to Human Happiness (1824)

William Thompson was an Irish philosopher and reformer: a pioneering socialist and an advocate of women’s rights. One of the earliest social scientists, Thompson was a practical thinker who believed the discipline to be, as Dolores Dooley writes below, ‘the science of happiness involving concrete proposals for a just society’. Despite his own lack of religious belief, Thompson championed the rights of others in the practice of religion, and – despite describing himself as a product of ‘the idle classes’ – was a lifelong advocate of equality for all. In the person of William Thompson, many strands of the humanist tradition are woven together, from the influence of Thomas Paine and Jeremy Bentham, through the reformist ideals of the freethinking Owenites, to the request for a non-religious funeral in line with his beliefs.

The biography reprinted below was first published in October 2009 as part of the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International license.

Contributed by Dooley, Dolores

Thompson, William (1775–1833), political economist and social reformer, was born in Cork city. His father, John Thompson, a wealthy merchant and landowner, was high sheriff of the county and, in 1794, was elected mayor of Cork city. John Thompson died in 1814 (his wife, of whom no other details are recorded, died 28 August 1825), leaving William 1,400 acres of land in west Cork. Few sources are extant for the early years of Thompson’s life until 1807, when he is listed in the records of the Cork Institution as one of its earliest members and financial contributors. His five major philosophical works show self-education in the philosophers and political economists of the eighteenth century, in the utilitarian theorists (especially Jeremy Bentham), and in the early sciences of genetics and psychology, agriculture, and law. His writings propose a philosophy of social science aimed at the pursuit of human happiness and the emancipation of human beings from the oppression of corrupt institutions. Thompson was one of the earliest social scientists, seeing the subject as the science of happiness involving concrete proposals for a just society. His subsequent eclipse in the history of political economy and feminist socialism was largely due to the way in which his radical ideas challenged the status quo of nineteenth-century Irish and English culture.

His writings propose a philosophy of social science aimed at the pursuit of human happiness and the emancipation of human beings from the oppression of corrupt institutions.

Thompson’s first major publication, a lengthy pamphlet entitled Practical education for the south of Ireland (1818) and addressed to Robert Peel, chief secretary for Ireland, was the product of a dispute at the Cork Institution. It detailed the ‘plan of a cheap and liberal system of education, adapted to active life, superior to what schools can teach’ (p. 44), but argued that mismanagement at the Cork Institution failed to deliver a ‘useful education’ for all classes, including the poor and illiterate. Thompson registered his public opposition to the abuse of public funds supporting the Institution by writing the pamphlet and distributing copies to lecturers in mechanics’ institutes in Britain, who might suffer similar financial misappropriations. The misuse of funds perverted, he believed, the goals of public education in Cork.

Further pursuing educational utility, in 1818 Thompson sent Jeremy Bentham plans for a juvenile institution modelled on Bentham’s Chrestomathia (1816) and encouraging positive motivation while eliminating corporal punishment. Lack of funding and of sufficient enrolment frustrated the implementation of this experimental school. The collaboration between Bentham and Thompson was the start of a long and productive relationship, culminating in a five-month stay in 1822–3 at Bentham’s home in Queen’s Square Place, London, at a time when Thompson and Bentham were both working on major works and exchanging suggestions for revisions.

Thompson’s Inquiry into the distribution of wealth (1824) is his best-known and most formidable work. It criticises the over-simplified theories of human nature of Thomas Malthus and William Godwin, and rejects La Mettrie’s view of man in L’homme machine, arguing that man’s creative psyche is not a mere machine ‘like a spinning jenny’. The analysis of human nature is preparatory for analysis of the main dilemma mankind faces, the most important problem of moral science: how to reconcile equality with security; how to reconcile just distribution of wealth with continued production. In undertaking this task, Thompson acknowledges the work of Adam Smith and Thomas Hodgskin while refusing to endorse their more conservative theses on the equal distribution of wealth.

Thompson criticised contemporary economics for concentrating on the production of wealth and ignoring its distribution, thus leaving in place radical inequalities of wealth among different classes. He argued that equality of wealth means not a naive assumption of equal shares of all goods for all people. Rather, equality meant comparable possession of the material goods required if self-determination was to be possible. Material goods consisted not only of property assets, but also education, access to positions in the public sphere, and most essentially civil, political, and domestic rights. Thompson presented various methods of systematically redistributing wealth and gave counter-arguments to his own proposals, anticipating objectors from classical economic theorists who saw redistribution of wealth as a violation of liberty. He also argued that equality with security is not possible unless three modes of labour are scrutinised: labour by force or compulsion, labour by unrestricted individual competition, and labour by mutual cooperation. He concluded that mutual cooperation was the best means to achieve equality in the distribution of wealth.

Thompson was acknowledged as the theoriser and realist practitioner for the projects of Robert Owen (1771–1858), whose charismatic approach to preaching the benefits of cooperation was viewed with scepticism by Thompson and other cooperative workers.

By 1824 Thompson was a committed worker in the cooperative movement in Great Britain, and in communication with the French utopian socialist Charles Fourier (1772–1837), who proposed the establishment of ‘phalanx’ communities to achieve human harmony in work. Thompson was acknowledged as the theoriser and realist practitioner for the projects of Robert Owen (1771–1858), whose charismatic approach to preaching the benefits of cooperation was viewed with scepticism by Thompson and other cooperative workers. In two subsequent editions of the Inquiry (1850, 1869) the editor, William Pare, excised some of Thompson’s more radical elements, among them the critique of inheritance viewed as antithetical to human equality. In this critique and in his analysis of human oppression Thompson reveals the influence of William Godwin’s ideas in Enquiry concerning political justice (1793). The 1824 Inquiry is acknowledged by Karl Marx as one of the treatises in political economy he had studied, taking abundant notes, when in Manchester in 1846. Thompson anticipated Marx in the theory of surplus value, and is the often unacknowledged source of much that appears in Marx’s understanding of ‘oppression’, his economic theories, and his critiques of class stratification.

In 1825, in the company of Bentham and utilitarians including the very young J. S. Mill and Frances Wright, Thompson established a special friendship and collaboration with the Irish feminist Anna Doyle Wheeler, who moved between France and London, liaising between Robert Owen and Charles Fourier. The collaboration of Thompson and Wheeler resulted in the publication of the Appeal of one half the human race (1825), a text now recognised as the first thorough analysis of socialist feminism. Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the rights of women (1792) was generously acknowledged by Thompson but he argued that it was wanting in its failure to press for economic changes to achieve the material means necessary if women were to exercise their rights.

In ‘An introductory letter to Mrs Wheeler’, Thompson explains the role of Wheeler as source of ideas and experience in recounting women’s oppression but also in the arguments for civil, political, and domestic rights for women. The impetus for the Appeal was James Mill’s treatise On government (1819), arguing that the intellectually disabled and women should be refused the franchise. When no repudiation of this position was forthcoming from Bentham or other utilitarians, Thompson penned the lengthy response of 1825. The text is a damning critique of the incoherence of the utilitarian thinkers of the day, purporting to defend the principle of equality of respect for all persons while denying the principle in their franchise proposals. The Appeal concluded with an argument that provision of rights is not enough to achieve the goal of human happiness; the redistribution of wealth is necessary for women to enjoy the material means for independence and self-determination.

Throughout his writings, Thompson recognised his privileged but unearned position of being male and a member of the propertied class.

The critique of capitalism and a rallying call to the working classes came in Thompson’s Labor rewarded (1827), taking as its point of reference the work of the political economist Thomas Hodgskin (1787–1869) in Labour defended against the claims of capital (1827). Thompson preferred the republican spelling of ‘labor’ and persisted in this linguistic statement of his allegiance to the democratic principles of Thomas Paine’s The rights of man (1791–2). Thompson addresses his 1827 work ‘to the industrious classes, my friends’ and refers to himself as ‘one of the idle classes’. This contrast introduces a discussion of the meaning of ‘productivity’. Using self-parody, Thompson challenges so-called mental labourers or intellectuals to demonstrate their ‘productivity’, as labourers daily must show their application in the sweat shops and farming fields of the time. Throughout his writings, Thompson recognised his privileged but unearned position of being male and a member of the propertied class. His critique of exploitative power reaches its apex in this 1827 work focused on the power of the privileged who perpetuate their own benefits to the detriment of the industrious classes. Labor rewarded provides a set of tightly reasoned arguments on the radical limits to human flourishing in the economic system of competitive individualism, and it stands in the philosophical canon as a vindication of the noble nature and social value of labour.

Daniel O’Connell was familiar with Thompson’s work and, specifically, his rejection of sectarianism and his political defence of religious freedom. Thompson’s earlier works persuaded O’Connell, in 1828, to have him appointed as chairman of the Liberal Club in Cork, an appointment strongly endorsed by Jeremy Bentham. By 1830 Thompson showed a sense of urgency about his life’s desire to establish a cooperative community based on a voluntary association of workers and their families. His Practical directions for the speedy and economical establishment of communities (1830) gave details of everything from educational programmes to architectural recommendations, including sleeping arrangements for parents and children, and exhaustive details of proper timing and methods for planting crops. The lands were at Thompson’s disposal from 1814 when, on the death of his wealthy father, 1,400 acres of land in Carhoogariff, near Glandore, Co. Cork, were left to this self-named ‘friend of the workers’. Approximately 300 cooperative trading fund associations through Ireland, Scotland, and England were established by 1830, and cooperative congresses, meeting in 1831 and 1832, were forums of debate and decision-making on policy and practices throughout Ireland and England. Delegates came with a view to thrashing out principles of cooperative association and deciding where such communities would be built. Thompson and Robert Owen were congenial collaborators at the first cooperative congress in May 1831 until William Pare proposed that Thompson’s plans be accepted as published in Practical directions.

By the third congress (1832), the collaborative brotherhood of Owen and Thompson had soured, with Owen feeling himself upstaged by the wide acceptance of the Irishman’s published plans. The themes and arguments of Thompson’s earlier works were expanded on as needed for the planning of the community; such arguments included the defence of women’s full liberty and participation in the cooperative communities, an idea which did not rest comfortably with some of the men workers prepared to join a community. More work of persuasion was needed, but unfortunately before building could commence Thompson’s frail constitution caused his death. Suffering persistent respiratory complications, Thompson died near Rosscarbery, west Co. Cork, on 28 March 1833.

Secondary grounds for hostility to the will were stipulations by Thompson that no religious ceremony be performed at his funeral. As a final gesture of social usefulness, he requested that his remains be given to science.

He had carefully detailed the terms of his will in July 1830, with Anna Doyle Wheeler and William Pare among the named trustees for its execution. However, Thompson’s ambitions of a lifetime were frustrated in death. He had left all his assets to the trustees to be used in the cooperative endeavours of forming communities. His two sisters, Sarah Dorman and Lydia Thompson, disputed the terms of the will on the grounds that some of the suggestions for living, marrying, and rearing children must be evidence of a deranged mind. Secondary grounds for hostility to the will were stipulations by Thompson that no religious ceremony be performed at his funeral. As a final gesture of social usefulness, he requested that his remains be given to science.

Thompson to the Rt Hon. Robert Peel, chief secretary for Ireland, 29 May 1818 (BL, Add. MS 40277, ff 300–01b); Thompson to Jeremy Bentham, 4 Oct. 1818 (Bentham MSS, University College, London, portfolio no. 18, xviii, 176); ten letters from Thompson, Weekly Free Press and Co-operative Journal, 6 Feb.–24 July 1830; Thompson to Lady Byron, 14 Aug. 1831 (Bodl., MS dept Lovelace Byron collection, 113, ff 75–6); William Pare, ‘Circular to London Co-operative Society announcing the death of William Thompson’, The Crisis, iii, no. 2 (14 Sept. 1833), 15–16; ‘Thompson’s will’, The Crisis, iv, no. 7 (24 May 1834), 55–6; John Minter Morgan, Hampden in the nineteenth century (1834), 301–25; Daniel Donovan, Sketches in Carbery (1876, reissued 1979); George Jacob Holyoake, The history of co-operation, i (1906); William Pankhurst, William Thompson: pioneer socialist (1954); J. F. C. Harrison, Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America (1969); James Coombes, Utopia in Glandore (1970); Cormac Ó Gráda, ‘The Owenite community at Ralahine, County Clare, 1831–33: a reassessment’, IESH, i (1974), 36–48; E. K. Hunt, ‘Utilitarianism and the labor theory of value: a critique of the ideas of William Thompson’, History of Political Economy, xi, no. 4 (1979), 545–71; Noel W. Thompson, The people’s science: the popular political economy of exploitation and crisis 1816–34 (1984); Gregory Claeys, Machinery, money and the millenium (1987); id., Citizens and saints, politics and anti-politics in early British socialism (1989); Dolores Dooley, Equality in community: sexual equality in the writings of William Thompson and Anna Doyle Wheeler (1996); ead. (ed.), Appeal of one half the human race (1997); Thomas Martin Duddy, A history of Irish thought (2002)

David Pollock was a towering figure in the humanist movement. A longtime member, activist, trustee, and former Chair, he was […]

Margaret Chappellsmith was a devotee of the socialist and secularist ideas of Robert Owen, becoming one of the Owenite movement’s […]

Universal rights are exactly that, universal, and one should not suddenly acquire different rights after a certain number of birthdays. […]

The Humanitarian League is a Society of thinkers and workers, irrespective of class or creed, who have united for the […]