To have thus assuaged the temper of controversy, to have softened much deep-seated prejudice and to have disposed some of the champions of contending principles to search for an honest synthesis of apparently opposite truths, is a happy issue upon which the originators of the congress may look back with thankfulness.

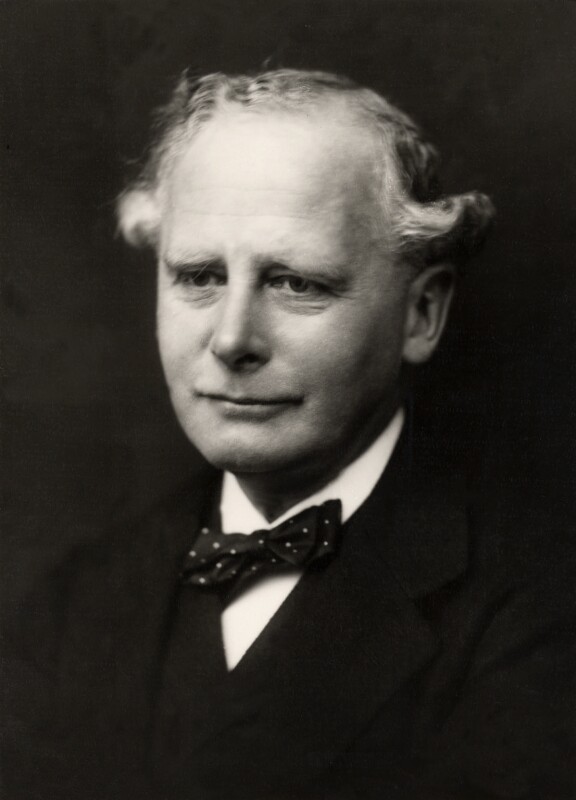

M.E. Sadler, ‘The International Congress on Moral Education’ in International Journal of Ethics, 1909

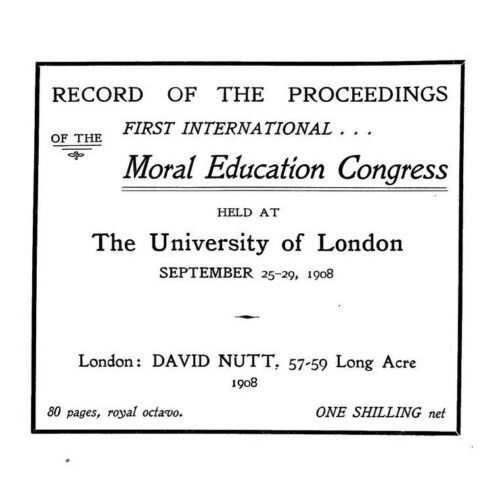

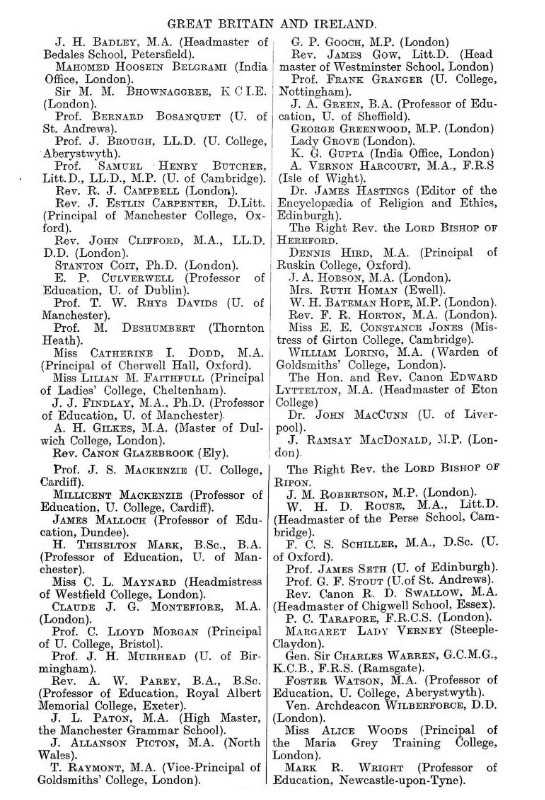

The First International Moral Education Congress was held at the University of London between 25-29 September 1908. It brought together delegates from across the world to discuss the use of non-theological moral education in schools, discussing a vast range of contemporary issues in education. This conference was the brainchild of the International Ethical Union (a forerunner of Humanists International), and organised in close collaboration with the Moral Instruction League, largely through the unstinting efforts of Gustav Spiller (who would also be central to the success of the First Universal Races Congress three years later).

The Congress sought, in the words of its President M.E. Sadler, to bring ‘men and women of very different schools of thought’ together for presentations and discussion, typifying the emphasis of the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK) on the use of cooperation and dialogue in bringing about progressive reform. Its delegates included representatives from the humanist ethical societies, as well as from an array of educational and religious bodies. Speeches were given in three officially recognised languages (English, French, and German) and, as Sadler noted, ‘an unusually large number of the speakers in the debates excelled in terse and lucid statement, some rising to a memorable level of moving eloquence’. In his report, he stated proudly that:

The success of the congress exceeded general expectation. The numbers attending were large, as many as fourteen hundred tickets being sold. At least eighteen nations, more than thirty universities and over a hundred educational organizations were officially represented at it. The general public took considerable interest in its proceedings.

Sadler went on to describe the spirit of the Congress as ‘one of intense sincerity, combined with forbearance and mutual respect’. Despite much divergence in principle and opinion, he wrote, ‘the truth was bravely told, but told with delicate regard for opposing convictions’:

A spirit of reverence and of respectful regard for the convictions of others prevailed in the congress, and united most of those present in a common search for truth and in a desire to reach a right judgment upon the momentous questions under review. The result was that many who entered the congress with distrust of the intentions of some of those holding opinions conflicting with their own, left it with widened sympathies and with the knowledge that they had learnt much from those who differed from them.

This spirit of internationalism, and central belief in the possibilities of dialogue, was at the heart of the Congress, and of the Union of Ethical Societies. The Congress’ organisers sought specifically to encourage the exchange of experience and initiatives across countries and cultures, and had conducted hundreds of interviews in Europe and the UK to establish a relevant programme. The publications of the Moral Instruction League had familiarised many with the ideals and emphases of systematic moral education, and a report – Moral Instruction and Training in Schools: Report of an International Inquiry – had been published prior to the conference, along with the key papers of the Congress.

Five further conferences were held in Europe between 1908–1934: in the Netherlands (1912), Switzerland (1922), Italy (1926), France (1930), and Poland (1934). Each of these discussed subjects of ongoing relevance to schools today, including the role of outdoor education, the development of civic responsibility, co-education of the sexes, and the place of religious instruction. Many prominent and pioneering individuals were speakers and delegates, such as Swiss educationist Adolphe Ferrière, and founder of the international Scout movement Robert Baden-Powell.

The impetus to establish such a Congress arose from, and enacted, some of the central humanist ideals of the Ethical movement: the effective and inclusive education of the young, and the facilitation of open, reasoned discussion and international cooperation. This emphasis on productive dialogue, collaboration, and working for progressive change continues to sit central to Humanists UK’s education campaigning today, the roots of which lie in the early efforts of the Moral Instruction League.

‘The International Congress on Moral Education’ in the International Journal of Ethics, January 1909

Un bouillon de culture pour les sciences de l’éducation?: Le Congrès international d’éducation morale by Marco Cicchini (University of Geneva)

No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; […]

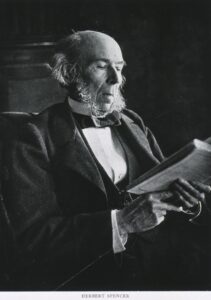

Without any great effort of thought, I believe that I could, in an instant, propose other systems of cosmogony, which […]

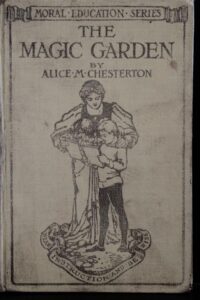

Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great […]

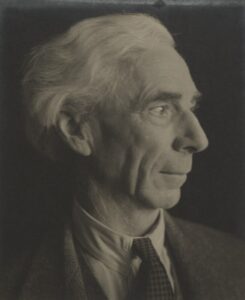

The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge. Neither love without knowledge, nor knowledge without love […]