America has a rich tradition of black humanism and freethought, frequently overlooked in histories of both the humanist movement and black life. Historians such as Norm R. Allen, Jr., Anthony Pinn, and Christopher Cameron have sought to shine a light on this heritage, asking, in Allen’s words:

Why has so little been said or written about black deists, humanists, agnostics, freethinkers, rationalists, atheists, etc., and how their intellectual freedom enhanced their effectiveness as leaders and thinkers?

Norm R. Allen Jr., African-American Humanism: An Anthology (1991)

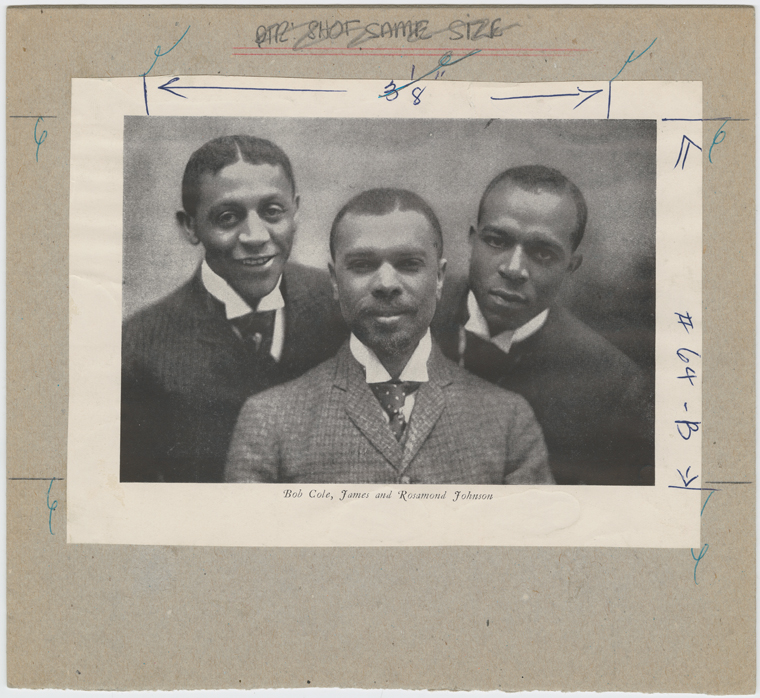

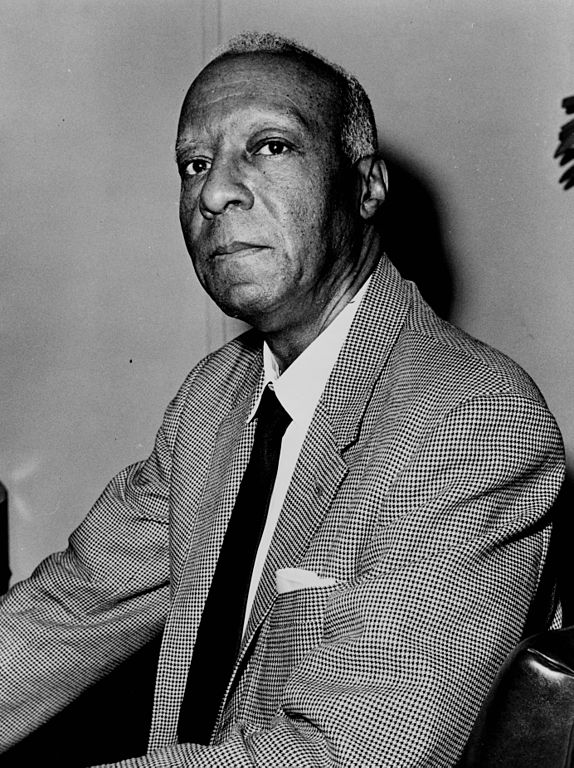

African American humanists have been influential artists, actors, activists, and academics, but – as has often happened with other non-religious figures in history – their humanist motivations haven’t always been acknowledged. And often, given the wider religiosity of black Americans, religious beliefs have been assumed. Using James Weldon Johnson (best known for ‘Lift Every Voice’, described as the black national anthem) as an example, scholar Anthony Pinn has warned against the assumption that black writers using religious idioms were necessarily believers. In The African American Experience in America he writes:

Those who argue that African American writers making use of African American religious idioms in their work are themselves committed to the religiosity expressed in their work are mistaken. While the sermonic style of African American churches is celebrated in God’s Trombones, it is clear that Johnson’s interest is in the tropes, idioms, and aesthetics of African American Churches.