Founded in 1263, Balliol College is one of the oldest colleges at the University of Oxford. Established by the English noble John de Balliol and his wife Devorguilla of Galloway, its earliest statutes required regular attendance at chapel and training in Catholic theology. Yet from its earliest centuries, Balliol has been associated with those willing to challenge religious orthodoxy — beginning with John Wycliffe, who as Master of the college in the 1360s promoted the intellectual movement that preceded the English Reformation. Ever since, a tension between religious tradition and intellectual dissent has been a defining thread in Balliol’s story, creating fertile soil for humanist ideas.

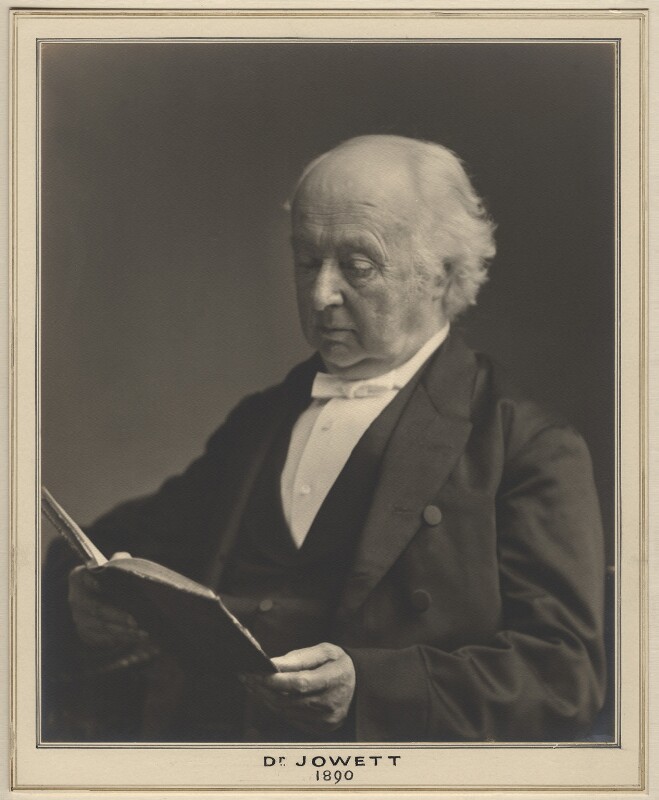

By the 19th century, Balliol had developed a reputation as Oxford’s most radical college. Its students and fellows were often at odds with the religious establishment, and it became known as a place where moral philosophy, classical learning, and political reform coexisted with — and often superseded — doctrinal faith. Master Benjamin Jowett encouraged biblical criticism, translated Plato, and mentored students whose questions often led them far from Anglican orthodoxy. In The Masque of Balliol, a student satire performed in 1881, the Master is lampooned as a kind of omniscient secular deity. ‘What I don’t know isn’t knowledge,’ he sings — a tongue-in-cheek tribute to the college’s veneration of learning, reason, and human inquiry over revealed truth.

By the end of the century, Balliol was producing scholars and reformers whose outlook was shaped more by the classics than by Christianity. Some, including an ancestor of Richard Dawkins, were drawn to the ‘Religion of Humanity’ proposed by Auguste Comte — a positivist vision of secular morality based on science and social progress. Others embraced liberal theology or abandoned religious belief altogether. In this ferment, Balliol helped to shape a modern British humanism: one rooted in ethics, scholarship, and social concern, rather than supernatural authority.

Despite the long roll call of names espousing egalitarianism and equality below, Balliol was one of the very last Oxford colleges to admit women for study, becoming co-educational in 1979.

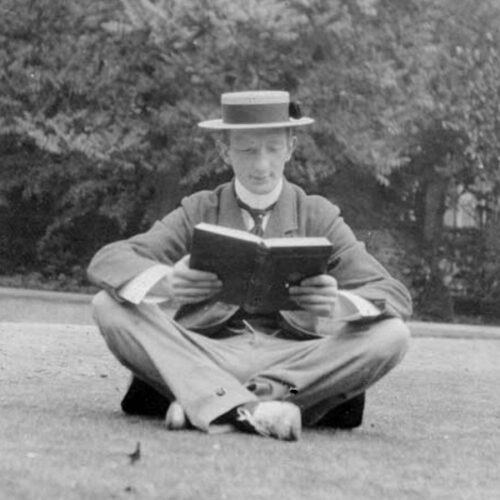

Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith came to Balliol in 1740 on a Snell Exhibition from Scotland, during a period of tension between Presbyterian sensibilities and Oxford’s High Church orthodoxy. Disillusioned by the religious atmosphere, Smith soon left and completed his studies in Glasgow, where he found intellectual stimulation among Enlightenment thinkers. Anti-clerical but not anti-religious, Smith was a deist who saw the moral order of the universe as discoverable through reason rather than revelation. His influential writings, particularly The Theory of Moral Sentiments and The Wealth of Nations, reflect a belief in natural sympathy and human flourishing grounded in rational inquiry, making him an important figure in the history of economic, moral, and political thought.

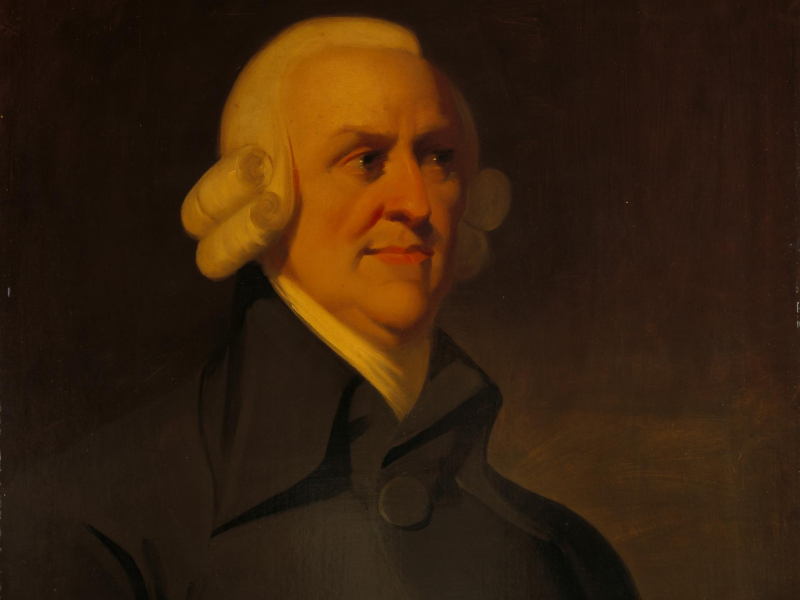

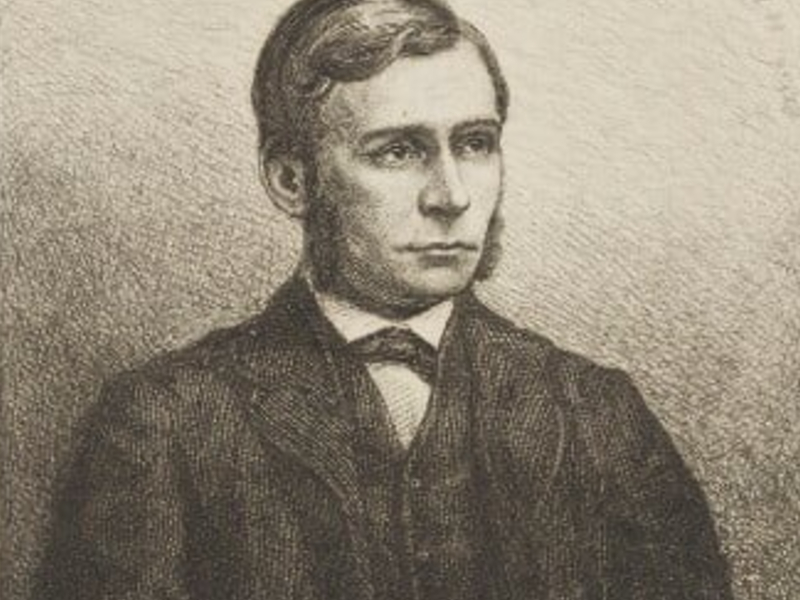

Poet and educationalist Arthur Hugh Clough studied and later taught at Balliol. Deeply troubled by his loss of religious faith, he resigned a fellowship rather than affirm beliefs he no longer held. His poetry, including The Latest Decalogue, reflects the inner struggle of a generation raised in Christianity but drawn to scepticism. In its honesty, ambivalence, and resistance to dogma, Clough’s work marks him out as a standout poet of the so-called Victorian age of doubt.

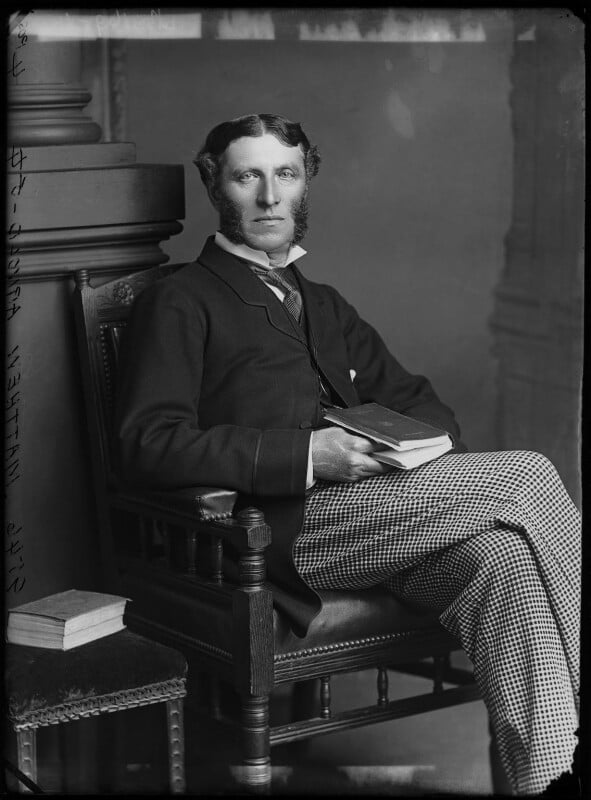

Poet, critic, and Inspector of Schools, Matthew Arnold studied at Balliol College during a period of growing intellectual restlessness in the Church of England — a tension that would come to define his life and work. Although raised within Anglicanism, Arnold became one of the most influential voices of the Victorian crisis of faith. His 1867 poem Dover Beach famously laments the retreat of religious certainty, describing how the ‘Sea of Faith / Was once, too, at the full,’ but now lies diminished, leaving only ‘its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar.’

For Arnold, the loss of faith was not cause for cynicism but for moral urgency: in a world ‘where ignorant armies clash by night,’ he called for human fidelity, compassion, and clarity. In prose works like Literature and Dogma, he argued that scripture should be read symbolically rather than literally, and that culture — meaning the best of human thought and art — must take up religion’s former moral role. His call for ethical seriousness without dogma, and for moral formation through poetry and learning, reflects his deeply humanist outlook.

T. H. Green was a philosopher and educator, who spent much of his life at Balliol – as a student, tutor, and Professor of Moral Philosophy. With his wife, Charlotte Byron Symonds, and others, he was instrumental in founding Somerville College: Oxford’s first non-denominational college for women.

Green’s philosophy focused on the capacity of human beings to apply reason, rationality, and individual will to their actions and moral life. His concept of personal freedom was not one of being able to do anything desired, but instead the capacity to use reason to align one’s actions with an understanding of the ‘good’. His emphasis on the practical applications of philosophy directly influenced some of the key figures in the early Ethical movement, including J. H. Muirhead and Bernard Bosanquet.

A rebellious poet, the atheist (and self-described ‘pagan’) Algernon Charles Swinburne studied briefly at Balliol before his behaviour led to rustication (suspension). His poetry was fiercely anti-clerical, celebrating classical myth and sensual experience while mocking Christian authority. Swinburne’s commitment to personal freedom and aesthetic defiance places him firmly within Balliol’s tradition of heresy and iconoclasm.

Anglo-German philosopher and Balliol graduate Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller was one of the first British thinkers to describe his worldview as humanism. Rejecting abstract systems and religious orthodoxy, he argued that truth should be understood in human terms — shaped by experience, purpose, and practical need. His work offered a distinctive alternative to both idealism and positivism, and helped introduce pragmatist ideas into British philosophy. Though later eclipsed by analytic thinkers, Schiller’s insistence that philosophy should serve human welfare marked him out as an early voice for a consciously humanist approach to knowledge and ethics.

A barrister and writer, Edmund Haynes studied at Balliol before becoming a prominent advocate for civil liberties and a vocal critic of religious orthodoxy. A committed atheist and rationalist, he published Religious Persecution: A Study in Political Psychology in 1904, tracing the psychological roots of intolerance throughout history. He moved in literary circles and maintained friendships with figures such as Edward Thomas, and later served as literary executor to Thomas Hardy — himself a noted humanist whose work wrestled with fate, doubt, and the human condition. Deeply committed to freedom of belief — including the right not to believe — Haynes’ life and work reflect a quiet but principled humanism, rooted in reason, scepticism, and the defence of individual conscience.

Architect of the welfare state and author of the 1942 Beveridge Report which paved the way for the creation of the welfare state and National Health Service, William Beveridge studied Classics at Balliol. He went on to forge a rational, data-driven approach to tackling poverty, identifying ‘five giants’ — Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor, and Idleness — which post-war Britain must defeat. Though not outspoken on matters of belief, Beveridge’s commitment to universal welfare and state responsibility reflected a secular ethic of justice grounded in evidence, not doctrine. His policies remain among the clearest real-world applications of a humanist vision of society.

In 1881, a group of Balliol undergraduates privately published The Masque of B–ll––l, a set of verses caricaturing their tutors and college life, offering a revealing glimpse into the intellectual atmosphere of late Victorian Balliol. At its centre is a wry portrayal of Master Benjamin Jowett, lampooned as an all-knowing oracle who declares, ‘What I don’t know isn’t knowledge’ — a gently irreverent reflection of the college’s reverence for scholarship and rational inquiry.

Historian Lesley Higgins says Jowett saw himself an Anglican but was regarded as a ‘heretic’ by students. He was by no means an atheist; his letters showed a man immersed in the Victorian zeitgeist of doubt and who read all the latest works by freethinkers, while holding onto a form of Christian faith. Jowett pushed a form of ‘rational religion’, which in his usage meant a reformed Christianity that accepted David Strauss’s fundamental contention that the Bible was largely a work of myth, yet retaining ‘faith in god and another world’. His attempts to reconcile his interest in rationalism with his devotion to religion runs through his letters to Florence Nightingale, and seemingly influenced his tutorials with students as well. Higgins reports one of his 1858 students as claiming ‘Jowett’s [religious] influence was negative to the extent that it reinforced my latent skepticism,’ while another who had received evangelical training attested ‘I fell under his influence with extreme reluctance, for I firmly believed that his pupils ran great risk of becoming strangers to the household of faith and denying the Lord that brought them.’

Whatever his personal beliefs, his influence on the liberal character of the college was unmistakable. He wrote to Florence Nightingale: ‘Is not all the mischief in the world done by conservatism and the world always cunningluy pretends that is really done by radicalism?‘

The Masque of Balliol provides evidence of the growing influence among students of positivism, the humanist moral philosophy of Auguste Comte, which sought to replace religious doctrine with a ‘Religion of Humanity‘ grounded in science and social order. One character, Clinton Dawkins — a Balliol student and ancestor of Richard Dawkins — is described as ‘a Positivist pure,’ suggesting that such ideas were not only familiar to undergraduates but embedded enough in college culture to be parodied.

While intended as affectionate satire, the Masque points to the shifting moral and philosophical allegiances of Balliol’s students, for whom liberal theology, classical ethics, and secular reform were becoming more compelling guides than the creeds of their forebears.

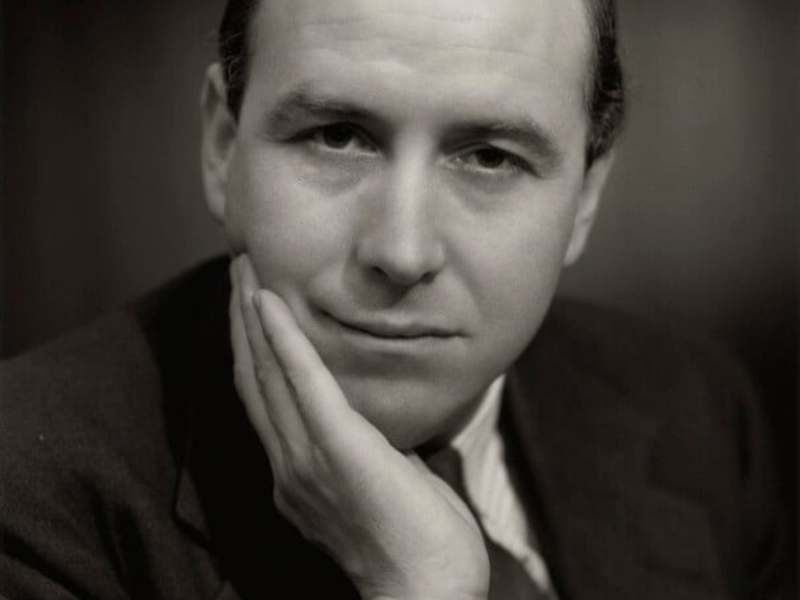

Philosopher, broadcaster, and Balliol graduate C.E.M. Joad was one of the most prominent agnostic public intellectuals of the mid-20th century. For years, he used his platform on the BBC’s Brains Trust to argue that moral behaviour did not require religious belief — a position he held until shortly before his death. Although he returned to Anglicanism late in life, the bulk of Joad’s career was spent advocating for reason, pacifism, and ethical humanism.

Diplomat, writer, and reforming politician, Harold Nicolson studied Classics at Balliol before entering a public life shaped by reason, ethics, and internationalism. In a 1999 New York Times essay, his son Nigel recalled that Nicolson was ‘adept at transmitting to his sons his own moral values, though he was not religious,’ and that he ‘could not accept [Christianity’s] paradoxes, such as a loving God capable of cruelty.’ Rejecting Christian orthodoxy, he embraced a secular ethic rooted in classical thought, personal responsibility, and tolerance. His political outlook, which he called ‘liberal realism’, sought to balance idealism with pragmatism — championing reform, international cooperation, and the moral integrity of public life.

Closely connected to the Bloomsbury Group, like many of them he lived an unconventional private life. Like his wife Vita Sackville-West, he was bisexual and polyamorous. Committed to one another, they maintained a long and loving marriage that accommodated their same-sex relationships – Vita’s lovers included Virginia Woolf. Nicolson’s many biographies, diaries, and essays reveal a life devoted to culture, conscience, and the moral imagination — all grounded in a recognisably humanist worldview.

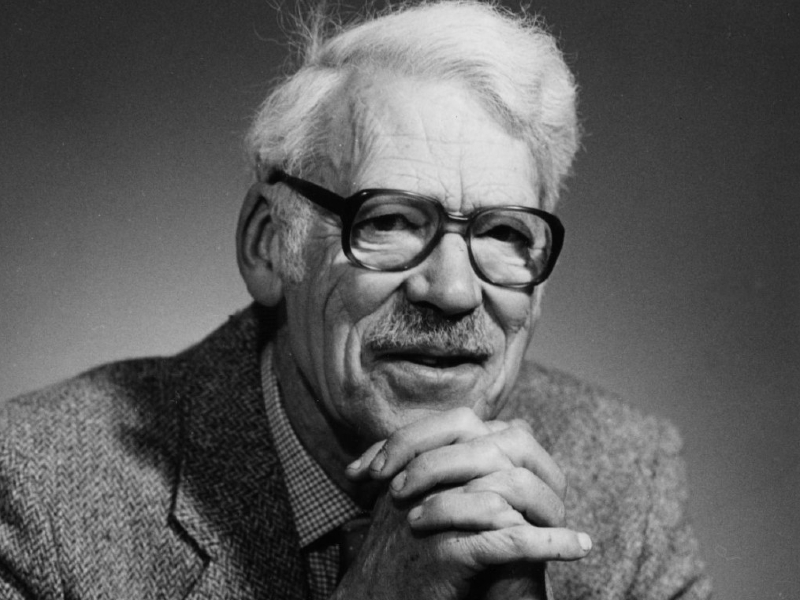

A student of zoology at Balliol, Julian Huxley became a pioneering evolutionary biologist and the first Director-General of UNESCO. A leading figure in organised humanism, he was a President of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) and a signatory of the Humanist Manifesto. Huxley rejected supernatural belief, arguing in Religion Without Revelation that science, philosophy, and the arts could provide meaning in a secular age. His belief in the evolutionary potential of humankind, tempered by rationality and compassion, made him one of the clearest exponents of modern humanist philosophy.

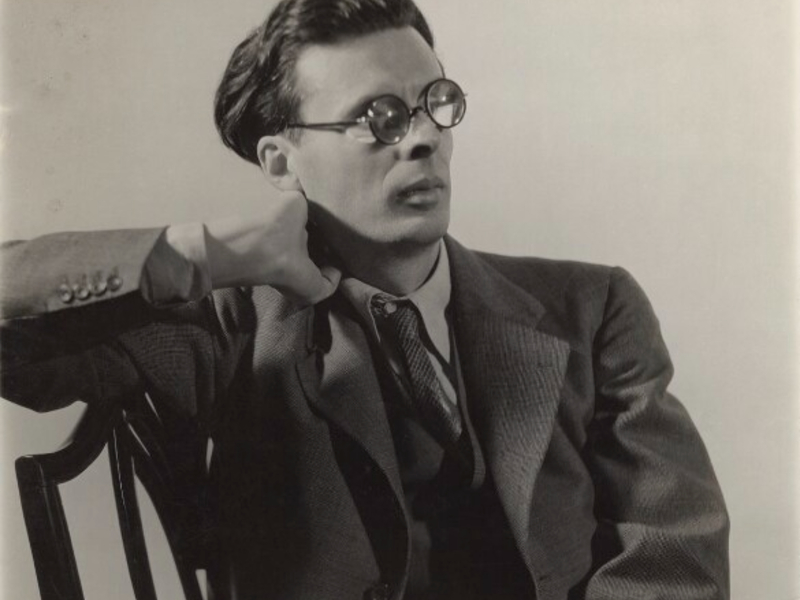

Though Aldous Huxley’s time at Balliol was marked by illness and interruptions, he emerged as one of the most enduring literary voices of the 20th century. His early novels satirised the pretensions of the upper classes, while his later work – especially Brave New World (1932) – questioned the costs of technological progress and the ethics of control. Huxley’s spiritual trajectory was eclectic, encompassing scepticism, mysticism, and psychedelics, but throughout his life he remained critical of dogma and open to ethical systems rooted in human experience. In its embrace of uncertainty, experimentation, and secular moral reflection, his work continues to resonate with humanist readers.

Political reformer Roy Jenkins read PPE at Balliol before going on to become one of the most influential statesmen of the 20th century. As Labour Home Secretary in the 1960s, he oversaw landmark legislation decriminalising homosexuality, liberalising abortion law, and abolishing capital punishment — reforms grounded in a vision of human rights and social progress. Later he was one of the Gang of Four who broke away from Labour to form the SDP and later the Liberal Democrats. Irreligious and privately humanist in his beliefs, his career reflected a consistent commitment to civil liberties and cultural pluralism. His pursuit of open societies (what he called the ‘civilised society’, and which was maligned by his enemies as the ‘permissive society’) places him firmly within a political tradition informed by reason, tolerance, and ethical human concern.

A classical scholar of exceptional candour, Sir Kenneth Dover read Greats at Balliol and went on to become one of the most influential Hellenists of the 20th century. His Greek Homosexuality (1978) broke with Victorian squeamishness to examine ancient attitudes to sex and the body with forensic honesty and scholarly rigour. In particular, he overturned the academic tendency – deferential to religious values – which denied or explained away homosexual acts along with gay and bisexual identities in the classical world, in the face of abundant evidence to the contrary. Dover identified as agnostic, and in his autobiography Marginal Comment (1994) he reflected on academic life and ethics with characteristic clarity, occasionally courting controversy. His commitment to truth over taboo, and his insistence that scholarship should face uncomfortable facts, marked him out as an inheritor of Balliol’s tradition of critical inquiry and intellectual freedom.

Engineer, politician, and human rights advocate Eric Lubbock, later Lord Avebury, studied engineering at Balliol before entering Parliament as a Liberal MP. A lifelong secularist, he was a patron of the British Humanist Association and a member of the All Party Parliamentary Humanist Group, and in 2008 played a key role in the abolition of the blasphemy law in England and Wales. He championed wide-ranging causes ranging from refugee rights to the welfare of prisoners abroad. Avebury was secular Buddhist, meaning he practiced Buddhist ritual and ethical approaches without supernatural beliefs. He also described himself as an atheist and a humanist.

Described as an ‘analytical philosopher with the soul of a general humanist,’ moral philosopher Bernard Williams studied Greats at Balliol, where he developed a lifelong engagement with classical thought and ethical complexity. An avowed atheist, Williams challenged the foundations of both utilitarianism and Kantian ethics, arguing that moral philosophy must account for the richness of human experience, emotion, and historical context. In works such as Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy (1985) and Shame and Necessity (1993), he explored how ancient Greek ideas of virtue and responsibility could inform modern secular ethics. His writing insisted that philosophy should grapple with the real difficulties of human life, rather than retreat into abstraction.

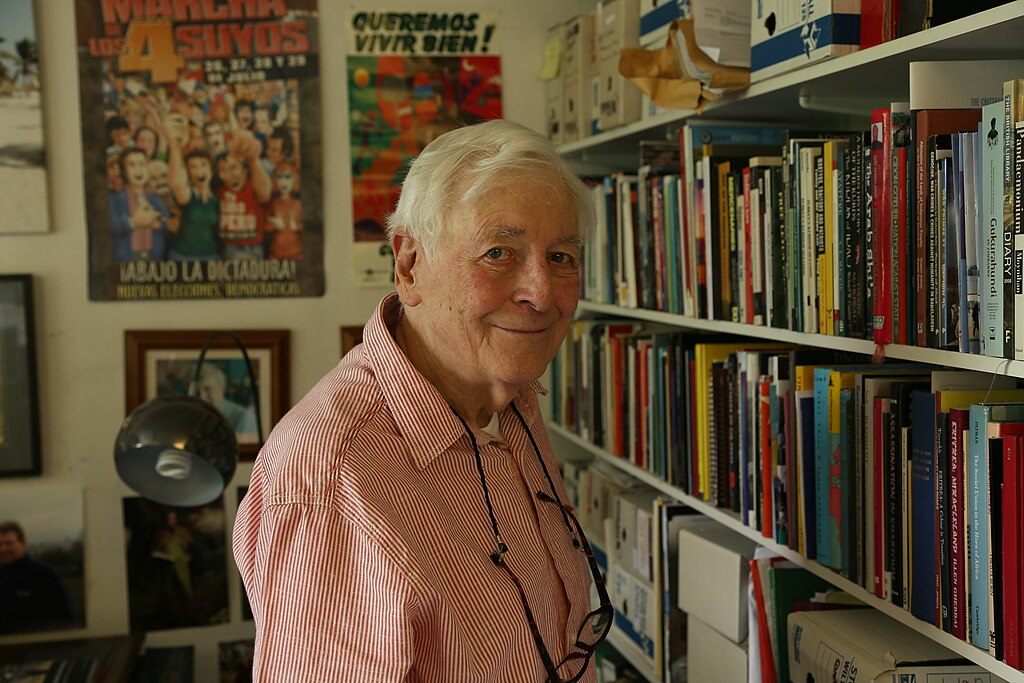

Historian and activist Raphael Samuel studied at Balliol before emerging as one of the most influential voices in the development of ‘history from below’. Raised in a Jewish communist household, he described himself as a Marxist and an atheist. A founding figure of the History Workshop movement, Samuel challenged traditional narratives and championed the voices of working people, community memory, and lived experience. His approach to history — collaborative, anti-elitist, and sceptical of established authority — reflected a humanist ethic grounded in dignity, pluralism, and intellectual honesty. Samuel’s life and work embodied key humanist values: critical inquiry, secular ethics, and a belief in the historical importance of ordinary lives.

Rationalist philosopher Martin Hollis was affiliated with Balliol as a tutor before becoming Professor of Philosophy at the University of East Anglia. A rationalist deeply influenced by the Enlightenment, Hollis argued that human understanding is rooted in shared concepts and mutual intelligibility — a view he termed the ‘epistemological unity of mankind.’ His work in the philosophy of social science emphasized the role of reason in explaining human action, resisting both relativism and reductionism, producing works of rationalist and humanist thinking with titles like The Light of Reason, The Cunning of Reason, Reason in Action, Trust within Reason, and Rationality and Relativism.

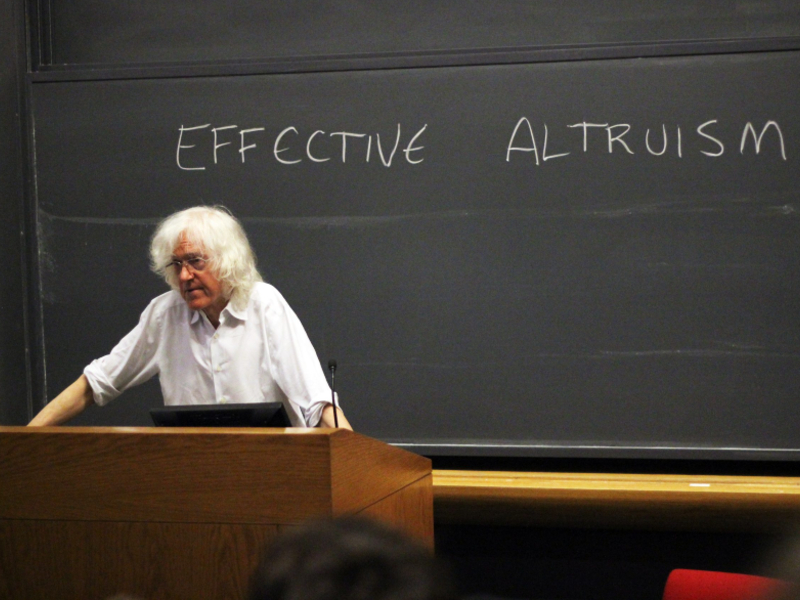

One of the most influential moral philosophers of recent times, Derek Parfit studied at Balliol before spending his career at All Souls. In Reasons and Persons (1984) and On What Matters (2011), he argued that ethics could be grounded in reason alone, without appeal to religion — making a powerful case for non-religious moral realism. His work emphasised impartiality, concern for future generations, and the moral importance of persons beyond rigid identities. Parfit’s influence on the Effective Altruism movement, and his belief in applying philosophy to real-world suffering, placed him firmly within the modern humanist tradition: committed to ethics, rationality, and the value of all human lives.

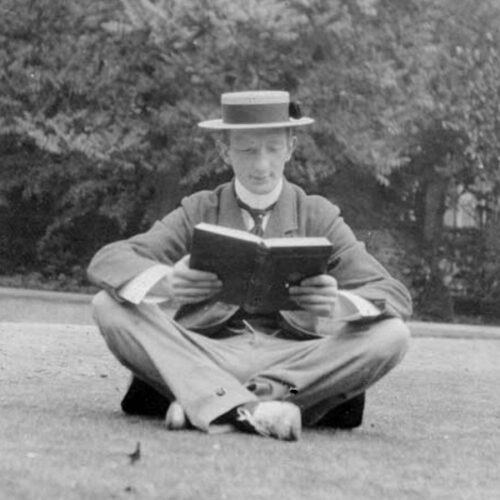

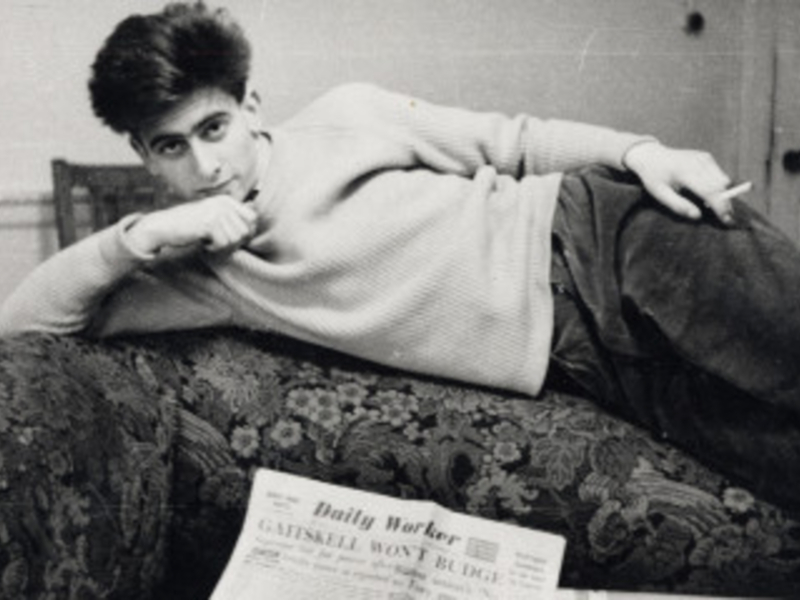

Writer, polemicist, and lifelong contrarian, Christopher Hitchens arrived at Balliol in 1967, already in possession of a sharpened intellect and a taste for rebellion. There he honed the rhetorical flair and iconoclastic instincts that would make him one of the most celebrated — and scathing — voices in modern atheism. A member of Humanists UK, Hitchens became a defining figure in the New Atheist movement alongside his fellow Balliol alumnus Richard Dawkins, championing Enlightenment values in the face of religious dogma. In God Is Not Great (2007), he memorably argued that ‘human decency is not derived from religion. It precedes it’ — a formulation that distilled his belief in reason, empathy, and secular morality. For Hitchens, the antidote to unreason was not just disbelief but a fierce and joyful embrace of literature, liberty, and the examined life.

Balliol’s legacy as a centre of intellectual dissent has continued into the modern era. In the 2010s, students challenged the religious framing of college events, reflecting an increasingly non-religious student body. In 2017, the JCR temporarily voted to ban all religious societies from freshers week events amid concerns about evangelism; the following year, it debated whether to rename the college’s Christmas dinner in protest at the overtly Anglican nature of college events for a diverse, largely non-religious student body. These recent tabloid-friendly rows — however brief or symbolic — point to the same spirit of independent thought and secular concern that has long animated the college’s intellectual life.

Balliol remains influential in modern ethical thought. Philosopher Toby Ord, whose doctoral research was conducted at the college, helped to found the effective altruism movement: a contemporary expression of utilitarian, non-religious ethics that applies evidence and reason to global moral questions. Many of the other leading figures in the movement gestated their ideas between colleagues and students at the college, before the movement jumped to the Ivies and Silicon Valley in the United States.

Balliol has continued to produce more than its fair share of high-profile humanists. Living examples associated with Humanists UK or the Rationalist Association include evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, Humanists UK Chief Executive Andrew Copson, broadcaster and historian Dan Snow, journalist David Aaronovitch, historian Professor Martin Conway, and monetary economist Dr James Forder.

Everywhere man blames nature and fate yet his fate is mostly but the echo of his character and passion, his […]

Humanism is… a tradition of thought and feeling combined with social action which stems from classical times and which has […]

Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to […]

They weren’t just trying to sell something to parents, they were helping them to understand how to play with and […]