Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought of reward on earth or in heaven.

Moncure Conway

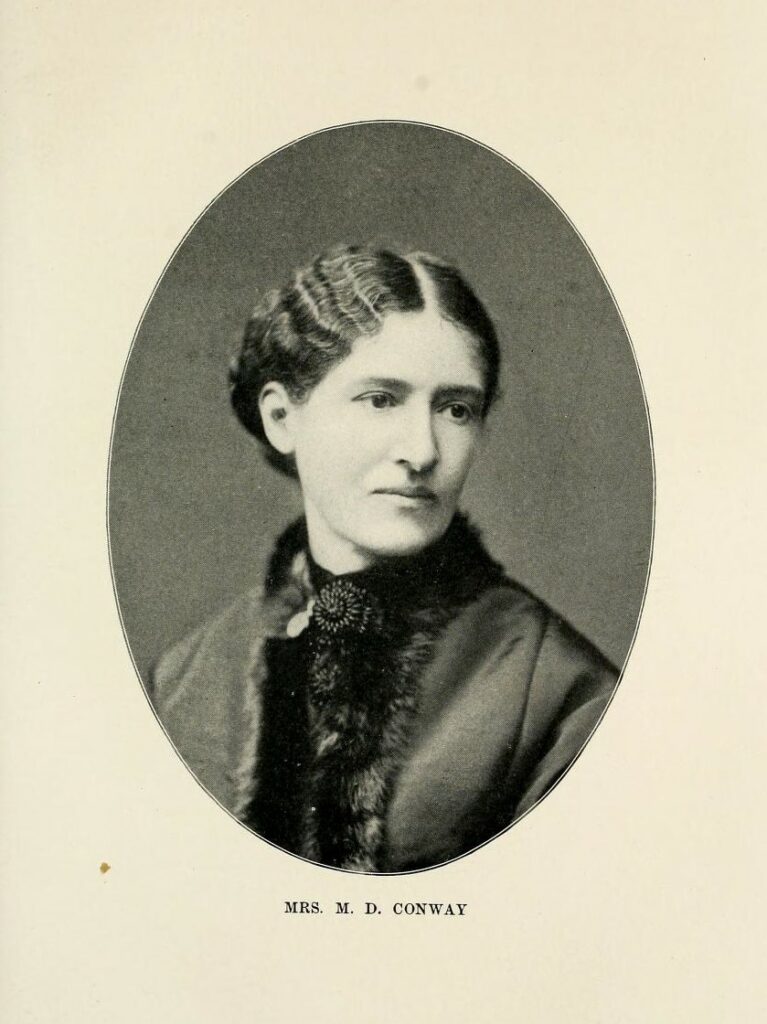

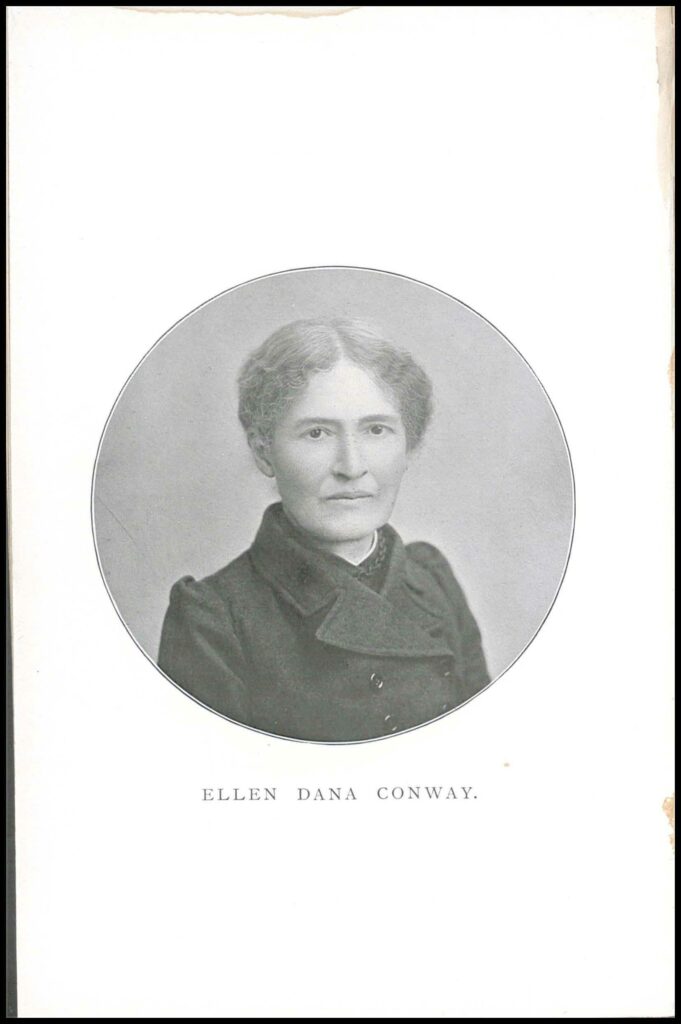

In spite of her noted influence and lauded character, Ellen Dana Conway has been little remembered when compared to her husband, Moncure Conway. Though credited by him as the impetus for writing his own memoirs, Ellen did not write hers, and impressions of her are drawn largely from the recollections of others. In these, her sociability and her humanism are evident, as well as her gentle but determined character.

Ellen Davis Dana was born in Cincinnati on 11 June 1833, the daughter of Charles Davis and Sarah Pond Dana. She married Moncure Daniel Conway on 1 June 1858, with a bridal party which included Samuel Longfellow, brother of the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. As later recalled by Moncure Conway, the young couple began their life together with little:

The first copy of my “Tracts for To-Day” was presented to my betrothed, and in it I find written: “Silver and gold have I none, but such as I have give I thee.” The words were more strictly true than most of our friends could imagine… But my bride and I regarded the poverty attending our first steps as a sort of joke.

Like her husband, Ellen Conway was a devoted abolitionist, described by him as being ‘as enthusiastic for the cause as myself’. She was his co-conspirator in transporting 31 enslaved people from Virginia to freedom in the North. The couple had a wide-ranging network of friends and fellow reformers, which included writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. While Moncure Conway was in England during 1863, Hawthorne in particular was a source of support for Ellen at home in America, where she experienced the condemnation by many of his outspoken antislavery position.

Her active support of her husband and the causes he pursued was a defining feature of Ellen Conway’s life. In extracts from her diary, included by Moncure Conway in his own memoirs, this is evident:

In February, 1863, my wife wrote in her diary at Concord now before me: “Wendell Phillips came to ask me if I would consent to my husband going to Europe to lecture and persuade the English that the North is right. Reluctantly I consented, feeling that as he was exempt from serving as a soldier [on account of his ‘right eye being too dim to sight a gun’] I had no right to prevent his being of service in some other way.”

Later that same year, Moncure Conway was invited to become the ‘minister’ at South Place, then still a ‘religious society’, but to become increasingly humanist under his leadership. Ellen too was devoted to South Place, and at pains to ensure social cohesion and comfort. Her efforts were recalled by Augusta E. Mansford, a longtime member of South Place, in the Ethical Record years later:

When Mrs. Conway first came to the Chapel, eager and ready to take warm interest in those brought together by her husband’s teaching, the high-backed forbidding pews depressed and repelled her… all were imprisoned in an unapproachable isolation, and her ideal of a society the members of which were in close touch one with another, working side by side and striving together for the attainment of a higher life, seemed impossible of realisation.

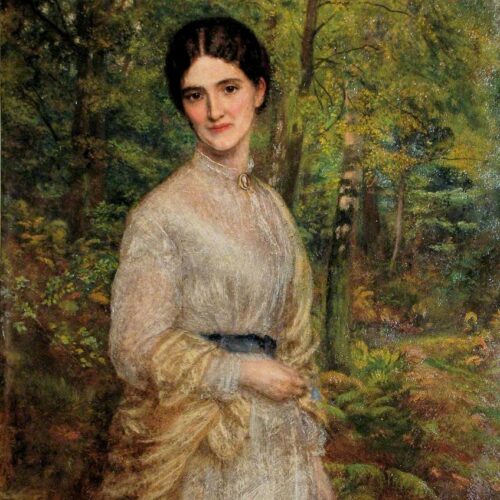

This ‘higher life’ was not of the supernatural or heavenly variety, but a rich and well-lived one on earth. Ellen Conway was described by another South Place member as having ‘a profound sense of beauty in all forms and phases’, and was a friend to artists and the arts. Her circle included Dante Gabriel Rosetti and David Dalhoff Neal, and she socialised readily with a host of notable figures from the period, including Alfred Tennyson and Robert Browning. In 1873, the artist Arthur Hughes produced an oil painting of Ellen, which hangs today in Conway Hall.

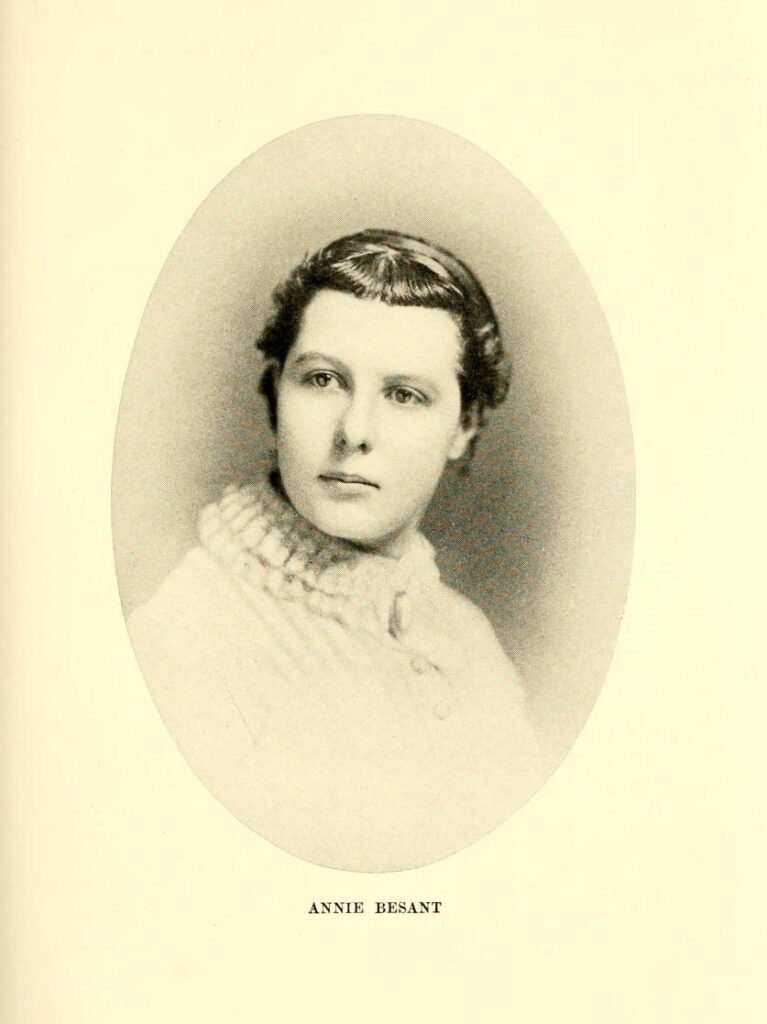

As a character, Ellen Conway was evidently warm and likeable, described as ‘often enliven[ing] the conversation with her wit and pleasant humour.’ She was also loyal and liberal, staunchly defending Annie Besant when she came under fire at South Place for expressing the belief that atheists could be admitted to the Society. Ellen Conway had invited Besant and her young daughter to stay with the family following Besant’s separation from her husband in 1873. In 1877, when Besant and Charles Bradlaugh went on trial for publishing birth control pamphlet The Fruits of Philosophy

while even many freethinkers stood aloof from her, Mrs. Conway, with characteristic loyalty, remained by her side during the long struggle and showed her unwavering kindness.

In her autobiography, Annie Besant credits Ellen Conway with her introduction to Charles Bradlaugh:

One day in the late spring, talking with Mrs. Conway — one of the sweetest and steadiest natures whom it has been my lot to meet, and to whom, as to her husband, I owe much for kindness generously shown when I was poor and had but few friends — she asked me if I had been to the Hall of Science, Old Street. I answered, with the stupid, ignorant reflection of other people’s prejudices so sadly common, “No, I have never been there. Mr. Bradlaugh is rather a rough sort of speaker, is he not?”

“He is the finest speaker of Saxon-English that I have ever heard,” she answered, “except, perhaps, John Bright, and his power over a crowd is something marvellous. Whether you agree with him or not, you should hear him.”

This openness to differing viewpoints, and devotion to airing them, characterised both Ellen and Moncure Conway. The two collaborated on the Sacred Anthology, a collection of texts which sought to make ‘the converging testimonies of ages and races’ more widely known. In organising extracts for the anthology underneath their various chapter headings, wrote Moncure Conway, ‘my wife and I fairly carpeted the floor with them’.

Behind all of Ellen Conway’s life and works lay a sense of duty and goodness entirely distinct from any notions of punishment or reward. Both South Place member Emma Phipson and Moncure Conway agreed that having ‘no superstitious terrors to daunt her’, and with the assurance of a life well-lived, she was unafraid of death. Her husband recalled:

About two months before her death I told her a happy dream I had, and asked her if she believed in immortality. She answered, “I know nothing about it. During my illness I also have had dreams and visions, but they have not suggested immortality. The chief thing is duty.”

‘Of the article of death,’ he wrote, ‘she was absolutely without fear or dread.’ In fact, even in sickness she was able to find ‘something good’, seeing the good works of her own life reflecting back on her.

Through all her active years she had been living for others, and when at last her hands were folded, it was with an almost infantine surprise that she saw others living for her.

Ellen Dana Conway died in New York on 25 December 1897, at the age of 64. A poem written by Emily Josephine Troup for the occasion contained the lines:

No dream of pure souls watching from afar

May live with us, perchance, to soothe and cheer;

But many a gentle thought of one so dear

Shall draw us higher like a deathless star.

So has it ever been; much of the best work at South Place originated from her.

Augusta E. Mansford

After her death, tributes to Ellen Conway described her sociability, humility, and the vital role she played in the running of South Place. Hers was a life free of superstition, and enriched by open-mindedness, unselfish compassion for others, and an appreciation of beauty. Through their own rejection of dogma and devotion to freethought, Ellen and Moncure Conway steered South Place towards humanism, and embodied the values of rationalism and kindness which characterise the humanist approach today.

Belfast-born Jack McDowell was an activist, educator, politician, and atheist, whose humanism was evident in a lifetime of work for […]

I have come to feel that the best proof of the subjection and degradation of my sex lies in the […]

What is needed is something in which [we] can all believe irrespective of religion, which in most cases, dare I […]

I was educated among the Saints; and I now live, thank God, among Sinners. David Williams, Essays on Public Worship […]