Emancipation from every kind of bondage is my principle. I go for the recognition of human rights, without distinction of sect, party, sex, or colour.

Ernestine Rose, Speech at the anniversary of West Indian emancipation, 4 August 1853

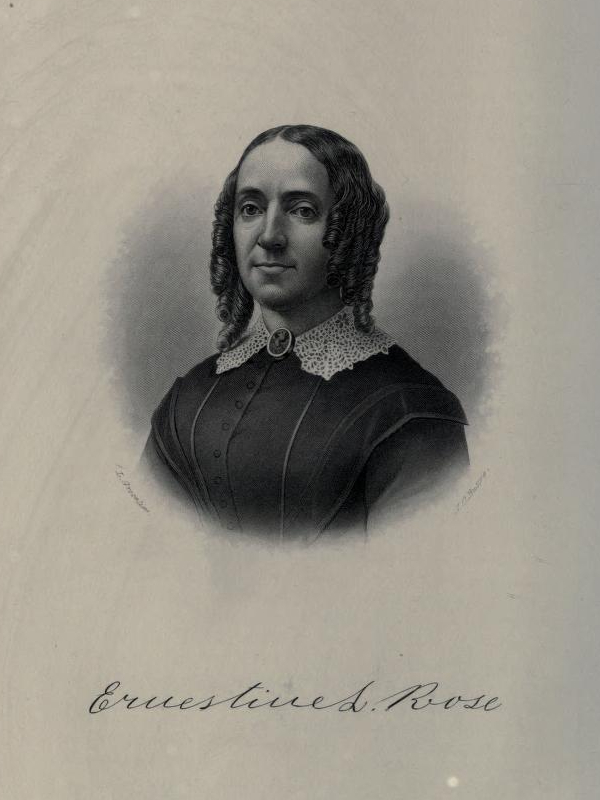

Polish-born atheist, abolitionist, and pioneering advocate of women’s rights Ernestine Rose combined a forthright rejection of religion with a passionate devotion to social reform. Rose had ‘a forcible voice, the most uncommon good sense, a delightful terseness of style, and a rare talent for humor,’ as one anonymous female journalist wrote in 1860, and she became infamous as a tireless freethinking feminist. Epitomising the ideals of thinking for oneself and acting for others, Rose forms part of a rich tradition of humanist women who devoted their lives to improving the one world they were sure of.

Ignorance is the evil – knowledge will be the remedy. Knowledge not of what sort of beings we shall be hereafter, or what is beyond the skies, but a knowledge pertaining to terra firma, and we may have all the power, goodness and love that we have been taught belongs to God himself.

Ernestine Rose, address to the First National Infidel Convention in New York City, 4 May 1845

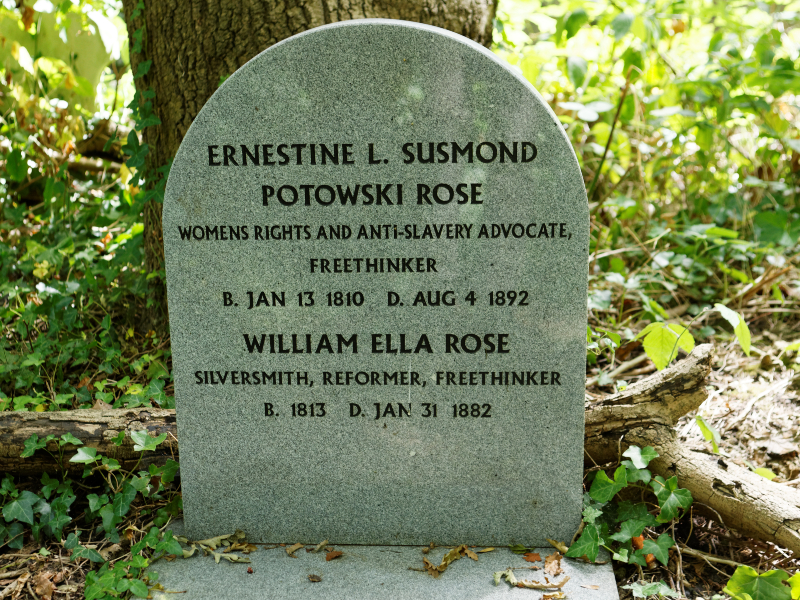

Ernestine Louise Potowski was born 13 January 1810 in Piotrkow, Poland, the daughter of an orthodox rabbi. While still a teenager, following the death of her mother, her father attempted to arrange a marriage for Ernestine, who rejected his chosen suitor (a much older man) and successfully sued her father for control of her inheritance. Sceptical of religion from an early age, Ernestine studied Judaism carefully before rejecting it while still young. She remained an outspoken atheist for the rest of her life, arguing above all for the right to freedom of thought and discussion, and the natural equality of all human beings. She firmly believed, drawing in part on her own experience in childhood, that religion was oppressive to women.

In 1827, at 17, she left Poland alone, travelling across Europe and living first in Berlin, where she tutored, and sold perfumed papers of her own invention. She arrived in London in 1830. There, Ernestine became an ardent supporter of reformer Robert Owen, whose vision for radical societal change and sex equality appealed to many fellow freethinking women – including Frances Wright, Margaret Chappellsmith, and Emma Martin. It was also in England that she met silversmith William Ella Rose, and the two were married in a civil ceremony. This loving and supportive marriage between two reformist freethinkers lasted until William Rose’s death, almost half a century later.

The couple emigrated to America in 1836, where Rose quickly embarked on a tireless campaign for reform – lecturing widely in favour of the abolition of slavery, and for women’s rights. Both hinged on an unflinching belief that every person was entitled to the same human rights, and the humanist conviction that the truth of this needed no supernatural sanction. The fairest and most humane laws, Rose believed, were those rooted in reason, underpinned by compassion, and arrived at through open discussion. This was clearly expressed in her 1861 lecture at Boston’s Mercantile Hall, entitled ‘A Defence of Atheism’, in which Rose stated her belief that:

We should work to get rid of irrational laws based upon sectarian opinions and to replace them by laws standing upon rational knowledge. We ask only the right to investigate everything, to throw it free and open, and to see if after examination we can arrive at something we can say we know.

Rose sent the first petition for a Married Woman’s Property Act (enabling married women to hold property in their name) to the New York state legislature in 1836. For over a decade, she continued to petition and to seek signatures, struggling against the unenthusiastic reception given to her by men and women alike. Writing later to Susan B. Anthony, Rose recalled that ‘no sooner did it become legal than all the women said, “Oh! That is right! We ought always to have had that.”’ In their history of the women’s suffrage movement in America, Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage – all three veteran activists and freethinkers – were careful to note Rose’s work for women’s intellectual, as well as political, emancipation. They wrote:

All through these eventful years Mrs Rose has fought a double battle; not only for the political rights of her sex as women, but for their religious rights as individual souls; to do their own thinking and believing.

History of Woman Suffrage, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage (1881)

Rose was always willing to work alongside, as well as to debate with, religious colleagues in the women’s rights and abolition movements, but was fervent in her belief that decisions about suffrage and slavery did not need the sanction of any religious text – or to be rooted in supernatural beliefs. Human reason was Rose’s ultimate authority.

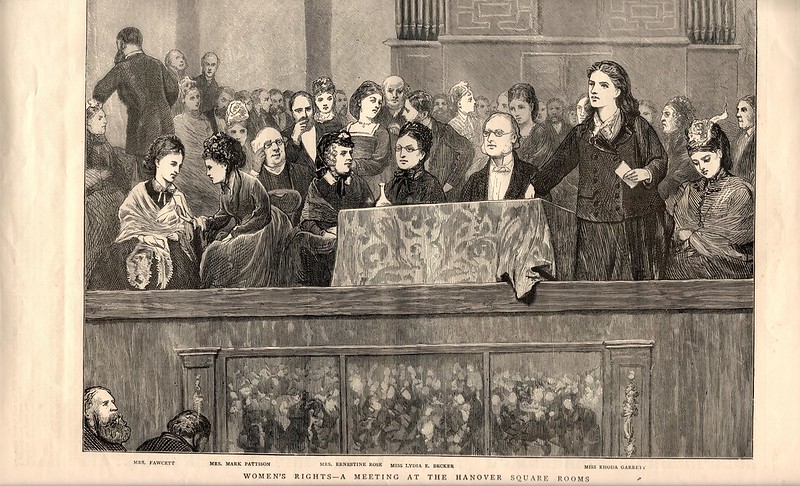

Ernestine and William Rose returned to England in 1869, where she continued to write and lecture on human rights and freethought. She was admired by, and friends with, many of the county’s most prominent freethinkers, including George Jacob Holyoake, Charles Bradlaugh, and Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner. In 1878, she spoke at the General Conference of Liberal Thinkers at London’s South Place Chapel, expressing once again those values which had animated her life. She argued:

Humanity, morality, and justice to man and woman, and non-interference with each person’s private opinions—for these ends we must work. We belong to the same human family, and we must work for it. Our life is short, and we cannot spare an hour from the human race, even for all the gods in creation.

General Conference of Liberal Thinkers at South Place Chapel, 14 June, 1878

Ernestine Rose died on 4 August 1892, having been careful to ensure that her freethinking friends were ready to defend her against any accusations of a deathbed conversion. She was buried at Highgate Cemetery, where George Jacob Holyoake delivered the eulogy.

Mrs. Ernestine Rose — a brave advocate of unfriended right — when age and infirmity brought her near to death, recalled the perils and triumphs in which she had shared, the slave she had helped to set free from the bondage of ownership, and the slave minds she had set free from the bondage of authority; she was cheered, and exclaimed: “But I have lived.”

George Jacob Holyoake, English Secularism: a Confession of Belief (1896)

She had no fears of death and passed away calmly, sustained in her last days by the same philosophy that inspired her noble, unselfish life.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, ‘Tribute to Ernestine L. Rose’ at the 25th Annual Convention of the Woman Suffrage Association, January 1893

An unabashed and self-described atheist, Rose was not only a pioneering activist, but a proud freethinker at a time when the open disavowal of religion still carried significant reputational risk. Even those who baulked at Rose’s irreligion could not deny her lifetime of active reform, with one English newspaper writing grudgingly on her death that ‘Mrs Ernestine Rose was that not very attractive or congenial individual, a feminine Freethinker, but in a practical way she did good service.’ Rose’s friend and colleague, the pioneering activist and social reformer Susan B. Anthony, felt that Rose was too ahead of her time to be truly appreciated in it, noting in 1854: ‘Mrs. Rose is not appreciated, nor cannot be by this age—she is too much in advance of the extreme ultraists even, to be understood by them.’ Nevertheless, Rose’s fierce advocacy of rationalism and humane social reform helped pave the way for generations of humanist women who came after her.

Ernestine Rose, ‘A Defence of Atheism’ (1861)

Ernestine L. Rose, Mistress of Herself: Speeches and Letters of Ernestine L. Rose, Early Women’s Rights Leader, ed. Paula Doress-Worters (2008)

Judith Shulevitz, ‘Forgotten Feminisms: Ernestine Rose, Free Radical’ | The New York Review

Pamphlets written by Ernestine Rose | Conway Hall

Ernestine Rose | Women’s National Hall of Fame

The hard anger she felt at the cruelty she encountered was always rooted in a deep tenderness for vulnerable humanity. […]

Bill Bynner was a humanist, socialist, and civil servant. As the editor of South Place Ethical Society‘s Ethical Record wrote […]

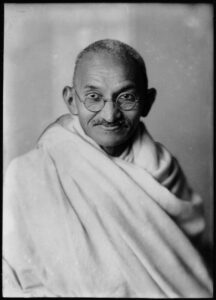

The international significance and reputation of Mohandas Gandhi is well-known, but his involvement with the burgeoning humanist movement during the […]

Living in a house beautifully situated on the outskirts of Coventry, they used to spend their lives in philosophical speculations, […]