I am willing and eager to surrender as much of my personal sovereignty as is necessary, in order to secure as much freedom as possible, not only for myself, but for all the members of the society. And here is the important thing—I know I cannot have any real freedom all by myself. I can’t have it unless everybody has it.

Eslanda Goode Robeson, American Argument (1949)

Eslanda Goode Robeson was a remarkable woman whose life was animated by her commitment to humanitarian causes. Eslanda, known as Essie, was an accomplished anthropologist, author, and actor, and a passionate advocate for social justice and civil rights: an anti-racist, anti-colonialist, and feminist. Described by her son, Paul Robeson Jr., as ‘agnostic’, Essie Robeson’s lifelong devotion to equality and freedom was animated by humanist values of personal responsibility, empathy for others, and a rational approach to human affairs. With her husband, performer and activist Paul Robeson, Essie spent many years living in London, studying at the London School of Economics (LSE), and involving herself in the causes close to her heart.

If Americans continue to slam doors around them, against their fellow men of different color, religions, economic and political beliefs, national origin, station in life—why then, very soon indeed, they will find themselves all by themselves in a badly ventilated room… there they will first become lonesome and sick, and will finally disintegrate.

Eslanda Goode Robeson, American Argument (1949)

Eslanda Cardoza Goode was born on 15 December 1895 in Washington, D.C. Although from a middle class family, she faced the challenges of racial discrimination from an early age. Despite these obstacles, she pursued her education with determination, earning a bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Columbia University, and going on to study at the London School of Economics. Her intellectual curiosity led her to anthropology, in which she earned a doctorate from Hartford Seminary.

In 1921, she married Paul Robeson, who—with Essie’s devoted support—went on to become a renowned actor, singer, and civil rights activist. The couple were actively engaged in the struggle for racial equality, and were outspoken supporters of left-wing causes, often at significant cost to themselves. On an international stage, the Robesons advocated for peace, anti-colonialism, and the rights of oppressed peoples around the world. Robeson felt deeply the interconnectedness of struggles across the world, a sense strengthened by global travel and periods living in both London and Moscow.

In 1927, the Robesons’ son, Paul (known as Pauli) was born. He would later write of the ‘variety of attitudes toward religion’ held by his family, describing Essie’s mother as having been ‘a militant atheist’, and his own as ‘agnostic’. In her writing, Essie Robeson acknowledged the significance of the church to African American communities, but channelled her own energies into global struggles against oppression, rooted in a profound sense of shared humanity. She saw her own experience as a black woman in America in the wider context of international struggles for freedom and equality. While she recognised her own achievements, she knew that no one could be truly free until all were. In 1949, she wrote:

Now I have everything that most people want, but I would like more people to have at least some of what I have.

Robeson’s international conscience was exemplified by her vocal stance against fascism, travelling to Spain in 1938 to support anti-fascist troops. In 1941, she co-founded the Council on African Affairs, an African American organisation dedicated to addressing the needs and concerns of African nations, and lobbying against colonialism. Robeson represented the Council at the founding convention of the United Nations in 1945. Her activism extended to issues including women’s rights, labour rights, calls for peace, and the fight against apartheid in South Africa. In June 1963, Robeson spoke at Conway Hall at an event organised by the Committee of Afro-Asian Caribbean Organisations (CAACO) in support of African Americans’ struggle for civil rights in her home nation.

In addition to her advocacy work, Eslanda Goode Robeson wrote or co-authored three books: 1930’s Paul Robeson: Negro; 1945’s African Journey; and 1949’s American Argument (with Nobel Prize winning writer Pearl S. Buck). She was a sought-after speaker, and the author of hundreds of articles and essays.

Diagnosed with cancer in 1963, Eslanda Robeson died on 13 December 1965. As her husband’s own health was poor at the time, her life was marked only with a small private service for immediate family, followed by cremation. In a special issue of Freedomways magazine, novelist and friend Alice Childress wrote:

Her days were freely given to building toward that peace based upon the fact of the brotherhood of man… The world is a better place because Eslanda Goode Robeson lived in it. I’m glad I knew her.

She loved life and she loved humanity. And to all whom her life touched she lent pleasure, luster and honor. In utter truth it can be said there is no one to take her place.

Ruth Gage-Colby, 11 December 1965

Although often overshadowed by the towering legacy of her husband, Essie Robeson’s unwavering dedication to humanitarian causes was profound, inspiring future generations to continue the fight for justice, equality, and human rights. Hers was a humanism with humanity very much at its heart—embracing those she knew, as well as strangers the world over. As her biographer Barbara Ransby wrote:

What a life. What guts. What resilience. What perspective. What a passion to live and speak and know and understand the world in all its amazing complexity… And what a capacity to love, to remain loyal, and to speak out with emphatic eloquence and steel-willed resolve against so many of the injustices of her day: McCarthyism, colonialism, sexism, racism, fascism. imperialism, wars (cold and hot), and class exploitation. Until her last days, she was tireless, unrelenting, vigilant, as well as thinking and “living large,” in the most meaningful sense of the term.

Barbara Ransby, Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs Robeson (2013)

Eslanda Goode Robeson and Pearl S. Buck, American Argument (1949)

LSE Women: Eslanda Robeson | The London School of Economics and Political Science

Not just a wife: the remarkable life of Eslanda Goode Robeson | Black Women Radicals

Against the militarist totalitarian state, I have striven. For the freedom of the human spirit to develop under the kindly […]

I have come to feel that the best proof of the subjection and degradation of my sex lies in the […]

Stanton Coit was a pioneer of the Ethical movement in England and the founder of the West London Ethical Society, […]

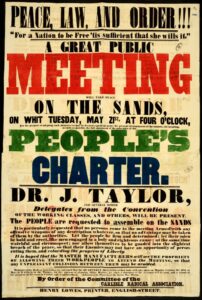

A mass working class movement for universal male suffrage Read more Chartist Ancestors and Women Chartists Chartism by David Avery […]