-

-

Beginnings

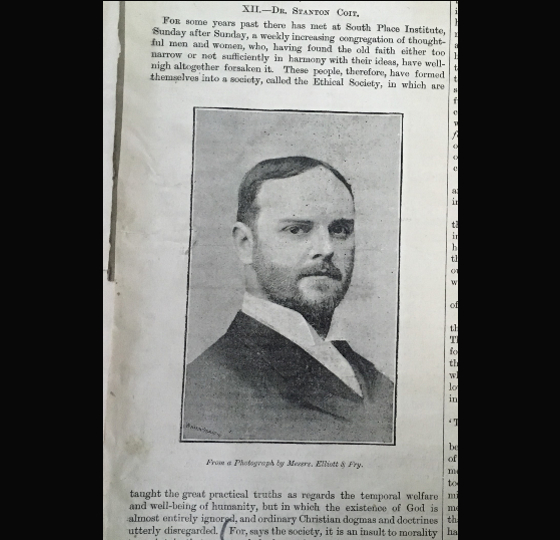

In 1891, Stanton Coit resigned from his leadership of the South Place Ethical Society.

In the words of F.J. Gould, Coit ‘was a fair-haired American from Ohio’, who ‘preached an admirable Humanist gospel in a happy alternation of smiles and hurricanes’, and his admirers at South Place hoped to find him a new home.

-

-

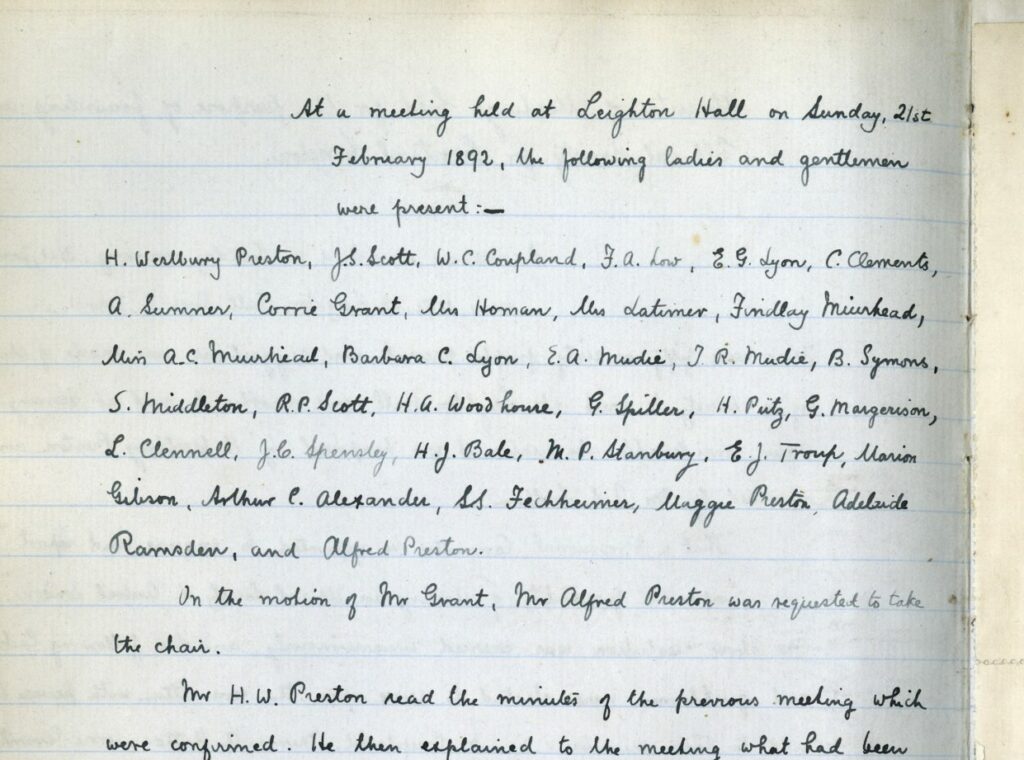

On 31 January 1892, as the minute book records, some 50 or 60 of these men and women met at Leighton Hall in Kentish Town, London, to discuss the formation of a new ethical society in central London.

-

On 21 February, they met again, their names dutifully recorded in the minute book. Among them were prominent figures in the early humanist movement, including Florence A. Law (daughter of forthright secularist Harriet Law); Gustav Spiller (who would go on to organise the First Universal Races Congress); and composer Emily Josephine Troup.

-

-

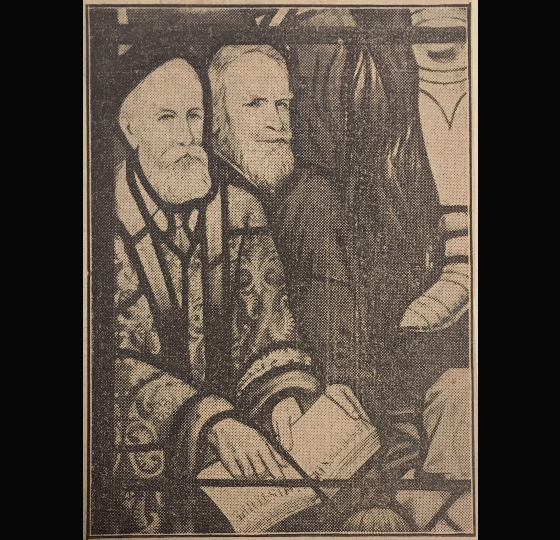

On Sunday 26 June 1892, 81 ‘subscribers and sympathisers’ met at Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly to agree aims and discuss progress. It was also announced that Leslie Stephen – first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography and father of Virginia Woolf – had joined the Executive Committee, along with the Earl of Dysart (William Tollemache).

-

Virginia Woolf; Sir Leslie Stephen by George Charles Beresford, 1902 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Virginia Woolf; Sir Leslie Stephen by George Charles Beresford, 1902 © National Portrait Gallery, London -

It was also resolved that the Society’s Sunday morning lectures would begin in October at Prince’s Hall, where a number of these early meetings had taken place.

-

Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly in 1883 (doorway visible on the left)

Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly in 1883 (doorway visible on the left) -

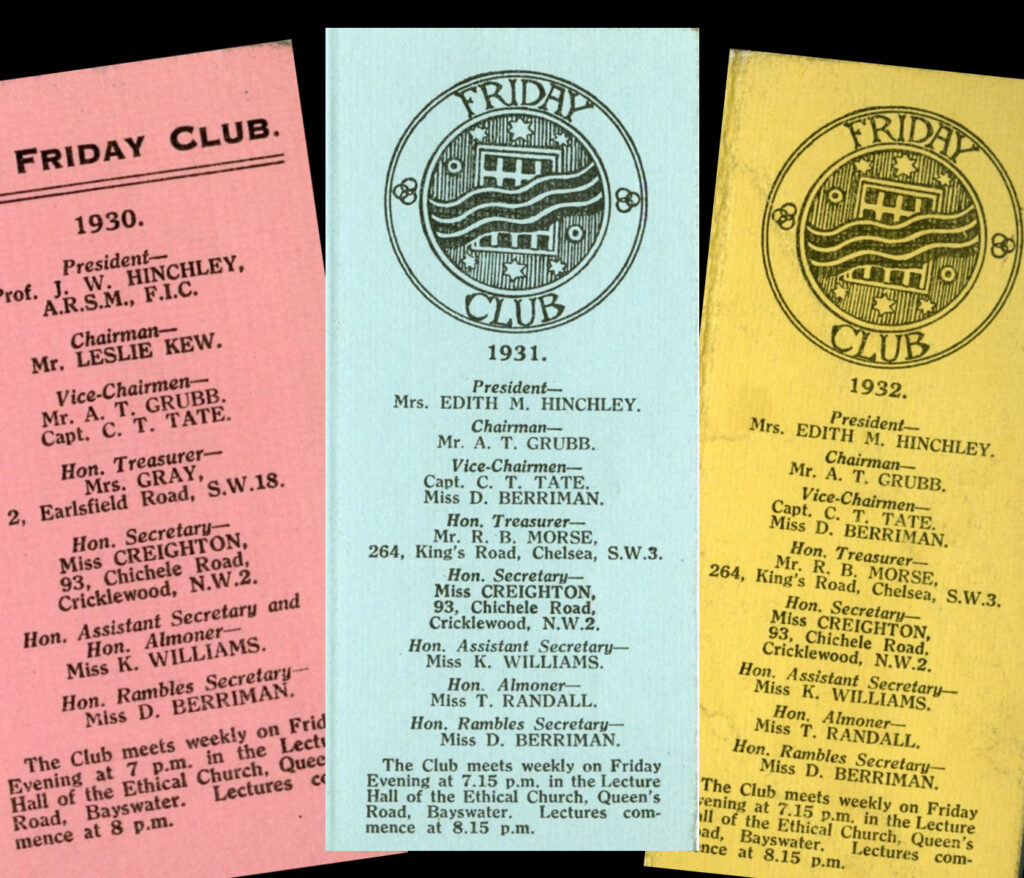

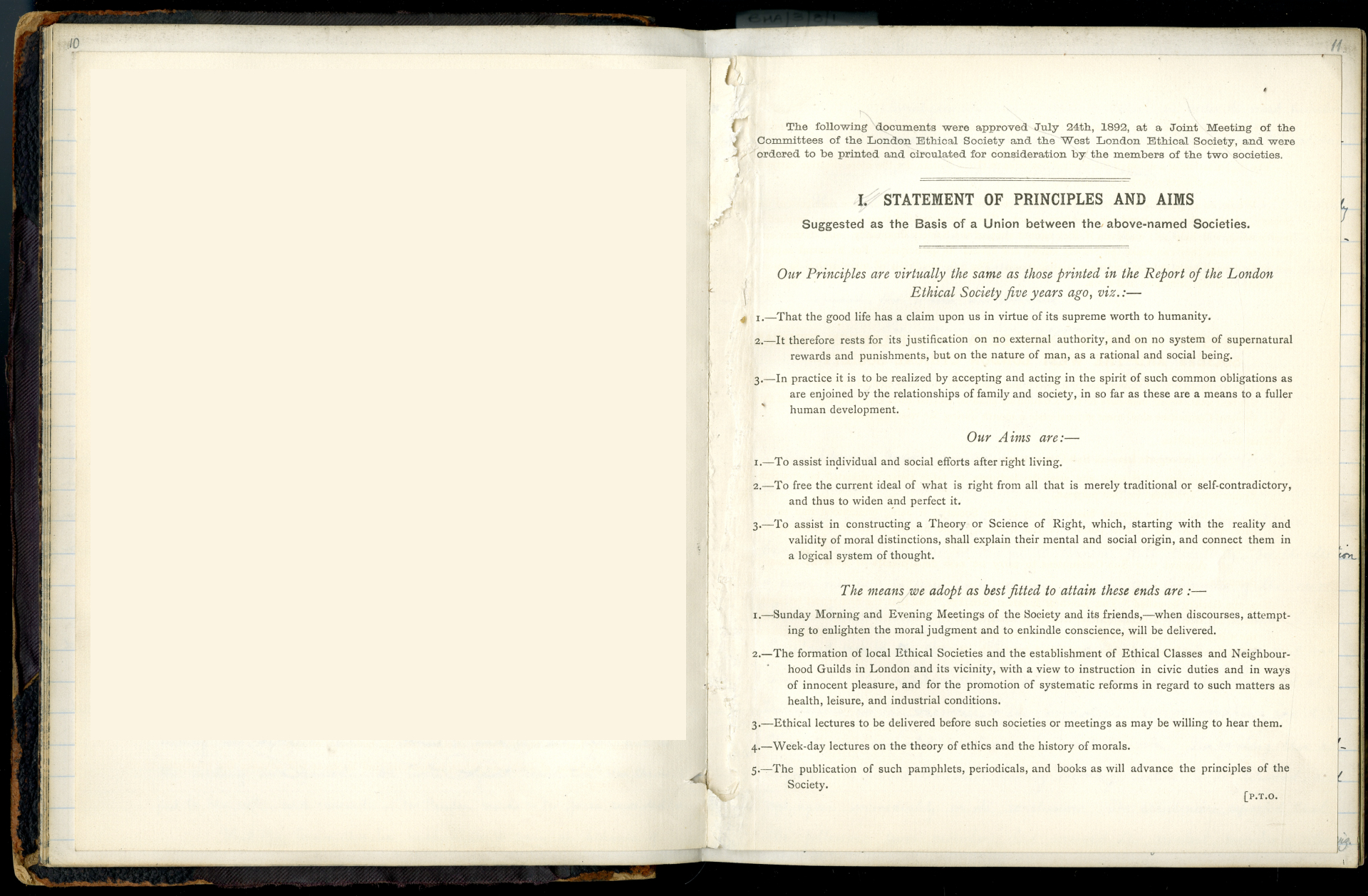

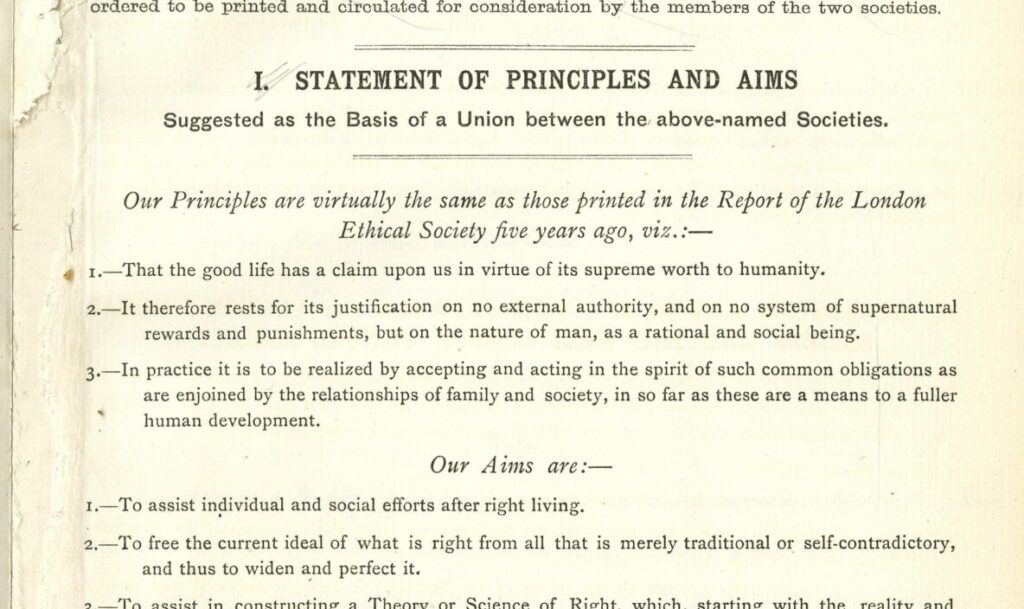

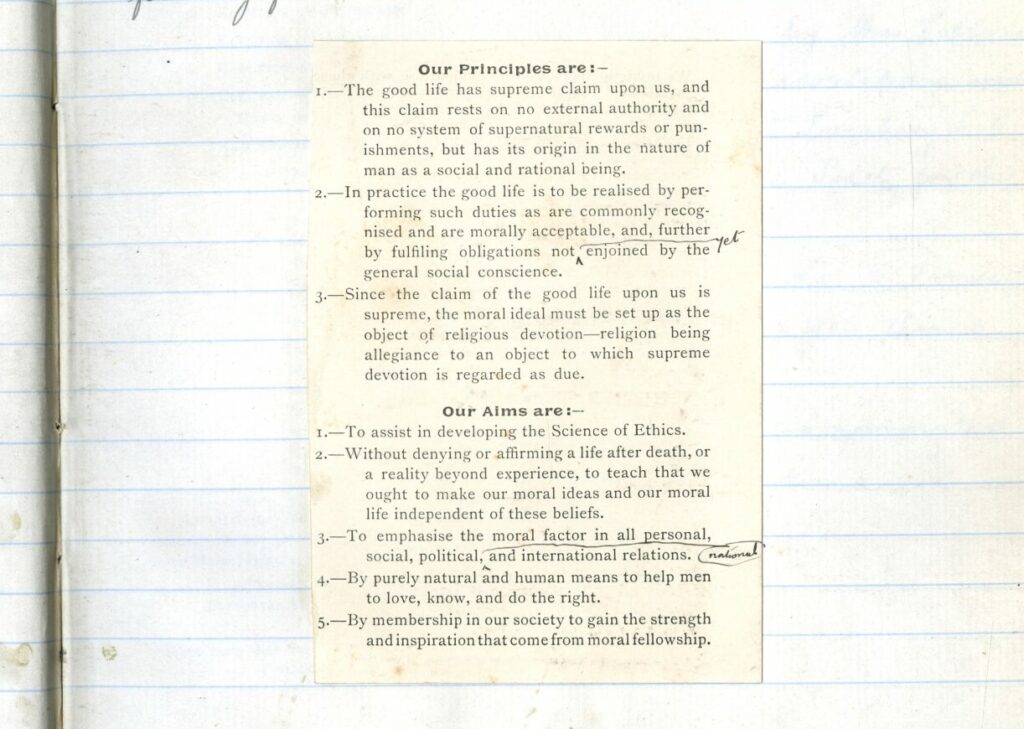

That summer, the West London Ethical Society agreed to join with the older London Ethical Society, founded in 1886. This wasn’t to last, but the jointly agreed Statement of Principles and Aims provides an insight to the character of the Society, and the wider Ethical movement.

For them, pursuit of goodness needed ‘no system of supernatural rewards and punishments’, and had its basis in ‘the nature of man, as a rational and social being’.

-

-

The union of these two London ethical societies was dissolved by agreement in June 1893. The West London Ethical Society’s annual report noted that ‘the cause which all the members had at heart could best be served by the two Societies working independently’, and expressed gratitude for the lessons learned.

-

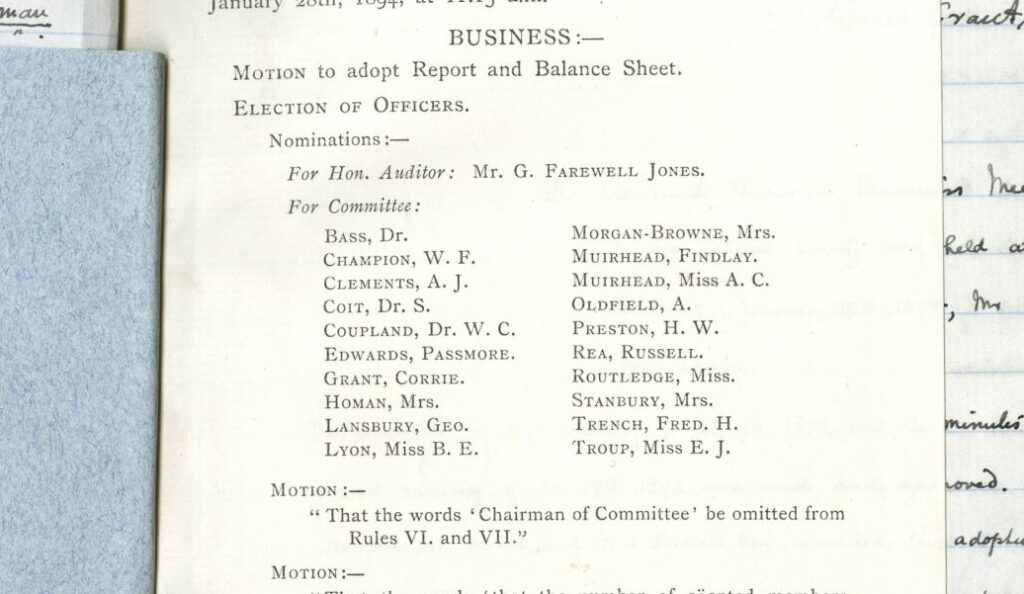

The following year, nominations for the Society’s Executive Commitee included philanthropists John Passmore Edwards and Ruth Homan, future Labour Party leader George Lansbury, and suffragist Laura Morgan-Browne.

The following year, nominations for the Society’s Executive Commitee included philanthropists John Passmore Edwards and Ruth Homan, future Labour Party leader George Lansbury, and suffragist Laura Morgan-Browne. -

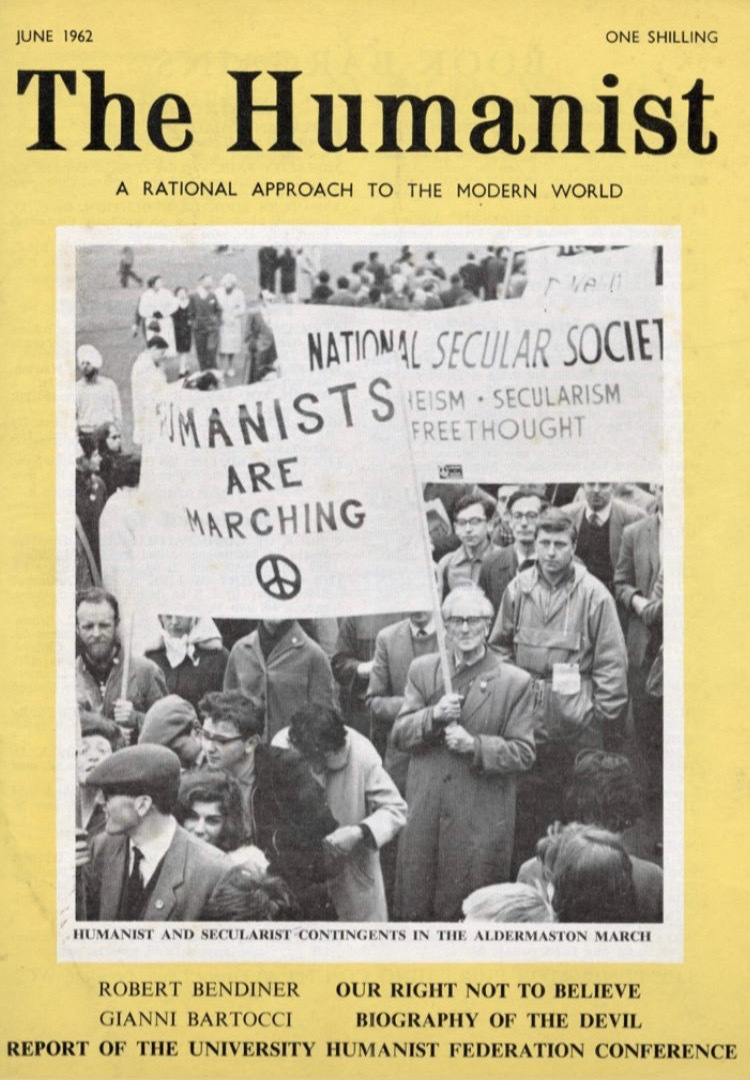

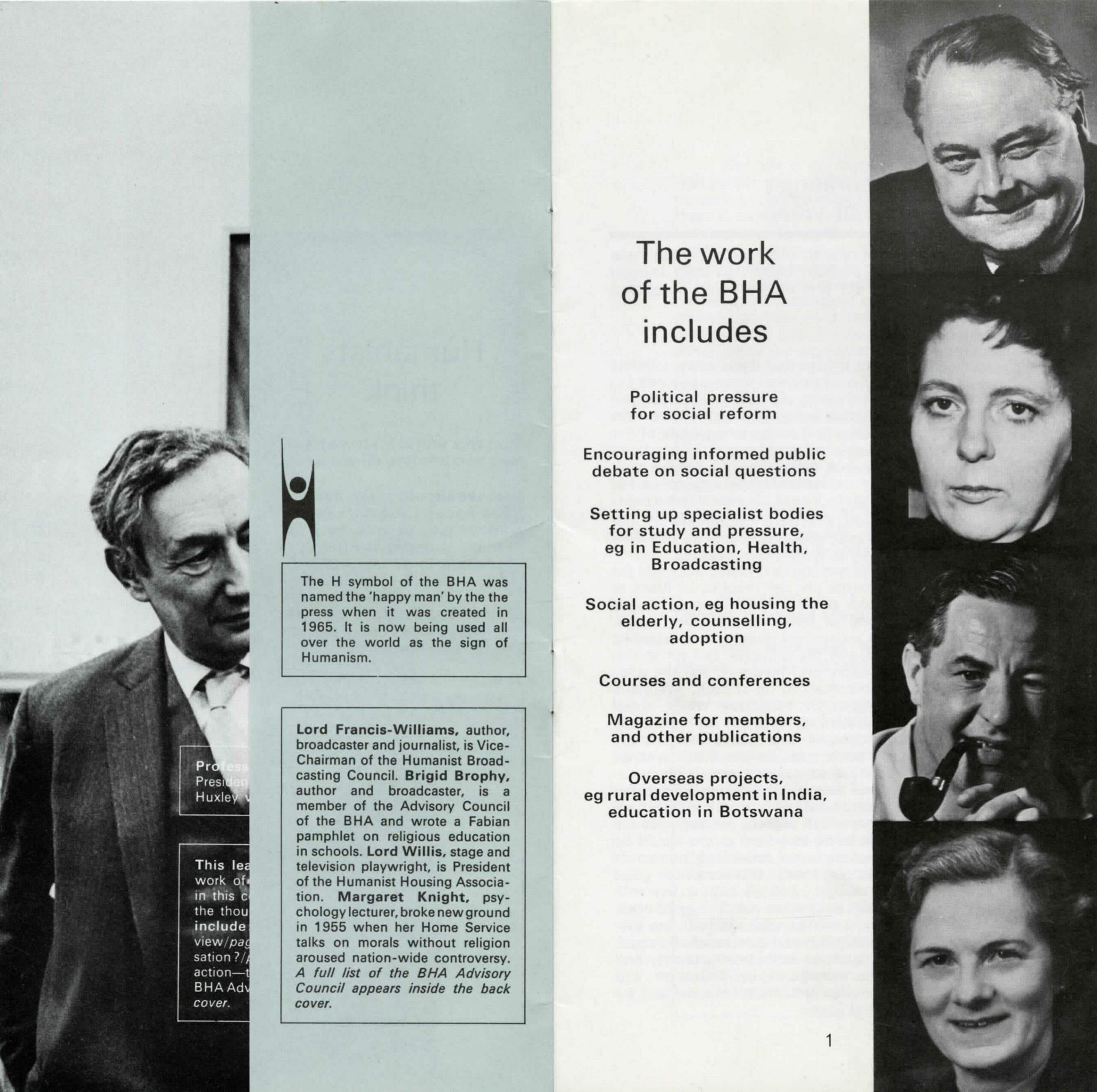

In 1896, the West London Ethical Society joined with others to form the Union of Ethical Societies. This would later become the Ethical Union, later the British Humanist Association, and ultimately Humanists UK.

-

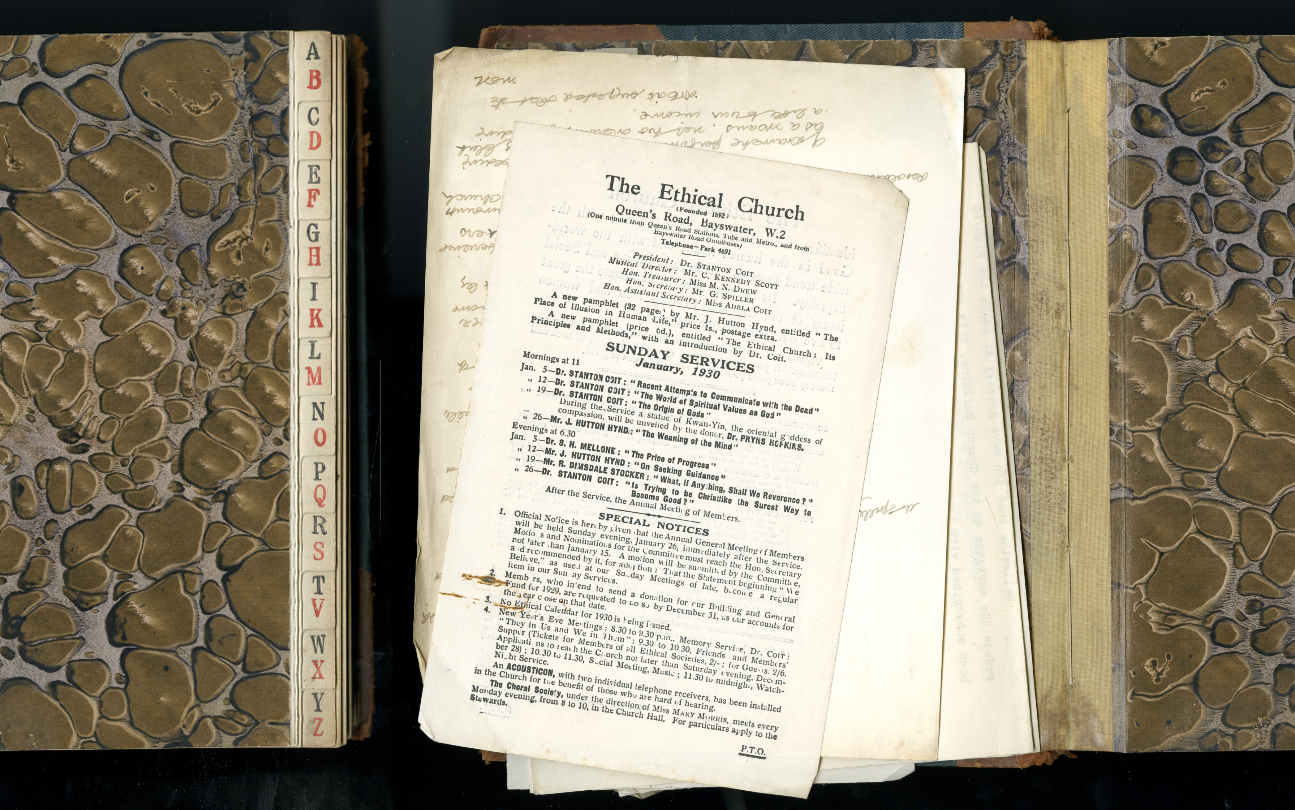

In December 1902, at a meeting held at 30 Hyde Park Gate (the home of Stanton and Adela Coit), updated Principles and Aims were adopted for the Society.

In December 1902, at a meeting held at 30 Hyde Park Gate (the home of Stanton and Adela Coit), updated Principles and Aims were adopted for the Society. -

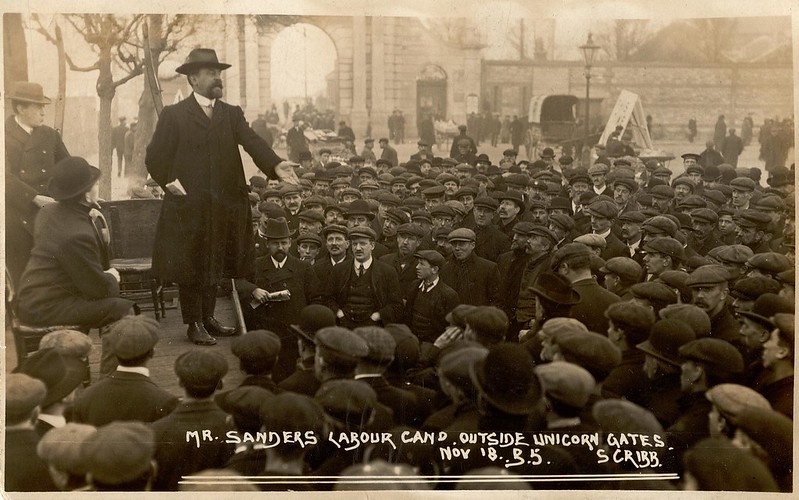

Chair of the meeting was William Stephen Sanders, a Labour politician and member of the Fabian Society. He and his wife, suffragist Beatrice Sanders, were decades-long members of the WLES.

-

William Sanders, 1910. LSE Library

William Sanders, 1910. LSE Library -

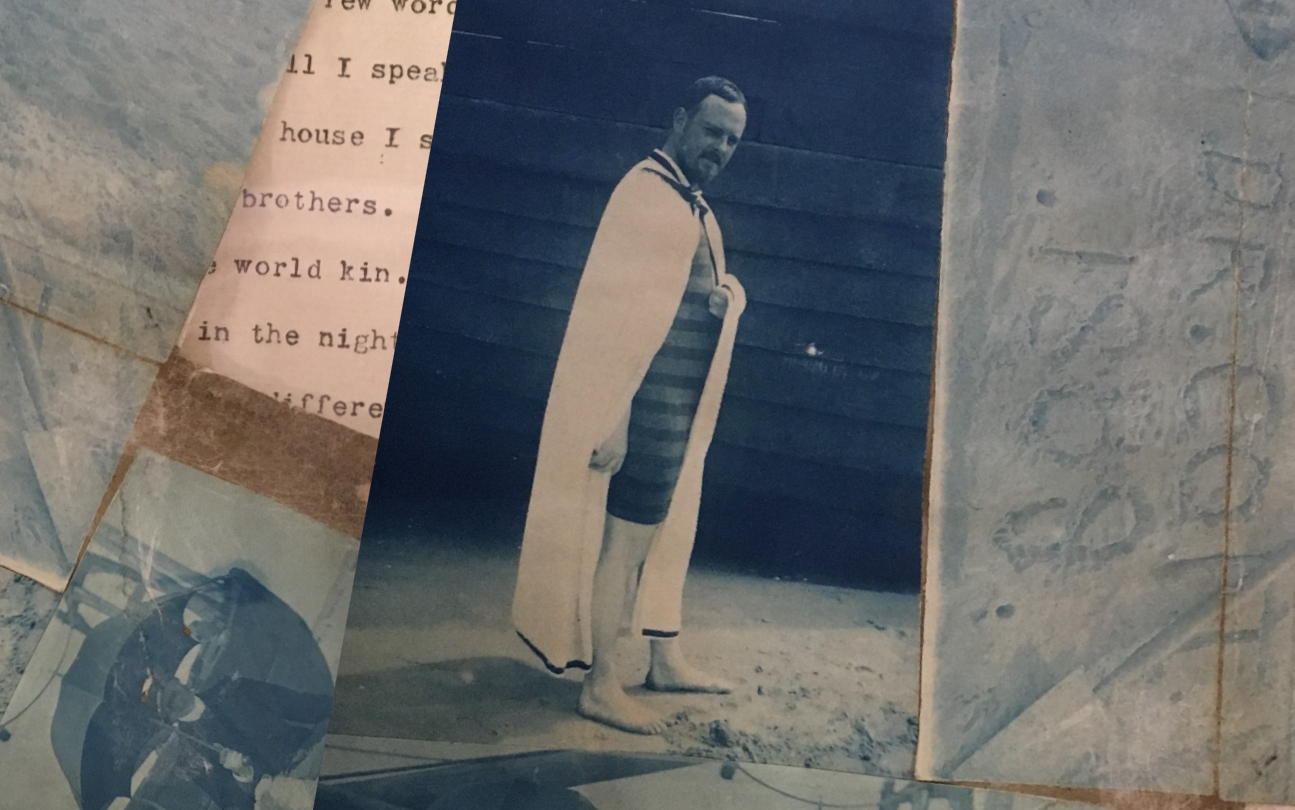

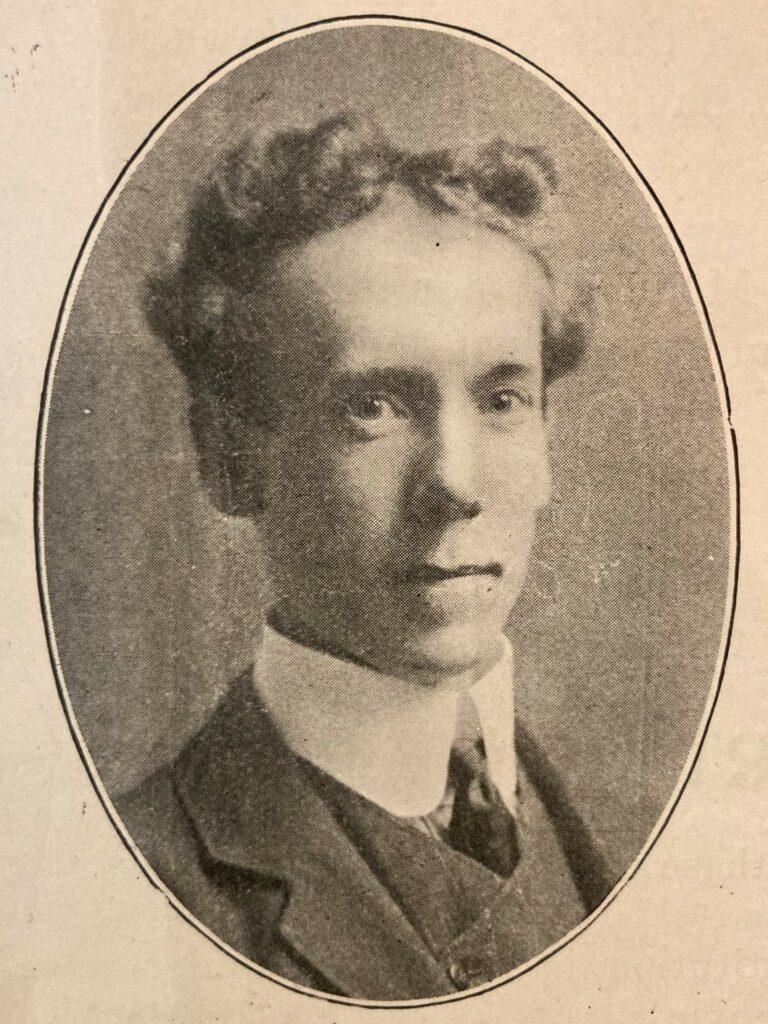

In February 1908, G.E. O’Dell was invited to become paid Secretary to the Society.

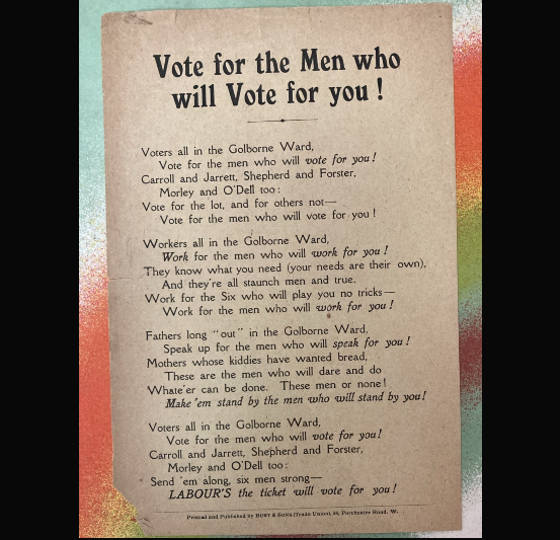

Like William Sanders, O’Dell was a socialist who took an active role in both politics and the Ethical movement. Two years earlier, he had run for election in the Golborne Ward of North Kensington as an Independent Labour Party Candidate.

-

G.E. O’Dell, c. 1906

G.E. O’Dell, c. 1906 -

Election flyer from the scrapbook of G.E. O’Dell

Election flyer from the scrapbook of G.E. O’Dell -

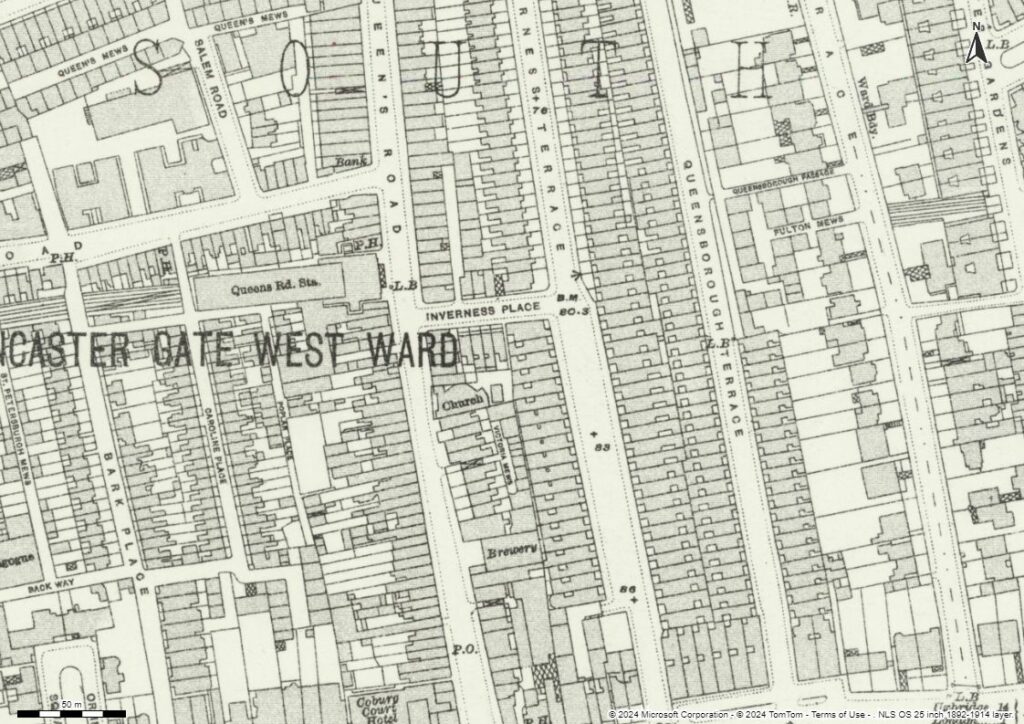

In March 1909, members of the Society were summoned to attend a special meeting. The matter to be discussed was the leasehold of a building – the United Methodist Church in Bayswater – to be outfitted as the WLES’ new home.

-

In this map, the location of what would become the secular ‘Ethical Church’ can be seen towards the centre, just below Inverness Place, on Queen’s Road (now Queensway), in West London.

In this map, the location of what would become the secular ‘Ethical Church’ can be seen towards the centre, just below Inverness Place, on Queen’s Road (now Queensway), in West London.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland CC BY 4.0 -

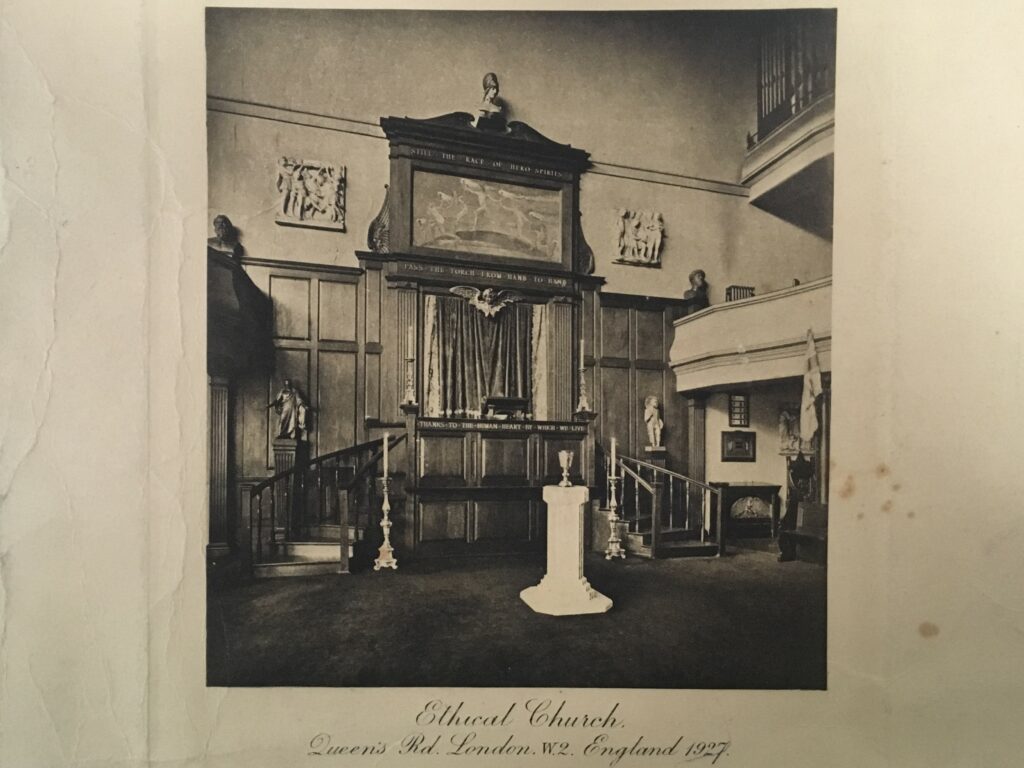

Over the following years, the West London Ethical Society transformed the space, with an interior designed by the artist and freethinker Walter Crane. A bust of Pallas Athene, Greek goddess of wisdom, held pride of place. Stained glass windows depicted figures the group admired – from writer George Bernard Shaw to reformer Elizabeth Fry.

Stanton Coit told the Daily Chronicle that they sought to honour contributors to ‘the freeing of oppressed humanity’.

-

-

-