What an emancipation it is, — to have escaped from the little enclosure of dogma, and to stand, — far indeed from being wise, — but free to learn!

Harriet Martineau, Letters on the laws of man’s nature and development (1851)

Harriet Martineau was a writer, reformer, and freethinker. Though born in Norwich, Martineau became active in the intellectual circles of London, and a close friend of William Johnson Fox, the radical leader of South Place Chapel (today Conway Hall). Martineau progressively abandoned the religious faith of her childhood, embracing instead a rich humanist philosophy focused on free inquiry, social conscience, and the pursuit of happiness.

…at length I recognised the monstrous superstition in its true character… and found myself, with the last link of my chain snapped, — a free rover on the broad, bright breezy common of the universe.

Harriet Martineau, Autobiography (1879)

Harriet Martineau was born in Norwich, into a then-comfortable Unitarian family, awake to political and philosophical questions. As a child and young woman, she was devoted in the study of her inherited religion, and devout in expressions of conviction. It was on these subjects that she generally wrote, and her first published essay appeared in the Unitarian Monthly Repository in 1822. In line with the rationalist and dissenting Unitarians, she was regularly and openly critical of the Church of England, whose unquestioning promotion of creeds and hierarchy she rejected.

The family business suffered from the mid-1820s, and failed completely in 1829. At which point, she wrote, she was free to live and not merely vegetate – thrown decisively on her own resources.

Many and many a time since have we said that, but for that loss of money, we might have lived on in the ordinary provincial method of ladies with small means, sewing, and economizing, and growing narrower every year: whereas, by being thrown, while it was yet time, on our own resources, we have worked hard and usefully, won friends, reputation and independence, seen the world abundantly, abroad and at home, and, in short, have truly lived instead of vegetated.

Martineau decided to live by writing, dismissing the alternative occupations open to her. In this, she was not unlike Mary Wollstonecraft, whose own financial uncertainties had cemented her devotion to making a living by her pen. In 1832, Martineau moved to London, where she was quickly embraced by William Johnson Fox and the radical political, intellectual, and literary circles to which he introduced her.

From 1834, Martineau spent nearly two years travelling extensively around the United States. A keen observer, and a sensitive recorder of impressions (she has been called the first woman sociologist), Martineau also became an outspoken critic of slavery. In America, among abolitionists, she became close friends with Maria Weston Chapman, who would be Martineau’s literary executor and biographer. On her return to England, she published Society in America (1837), and the following year How to Observe: Morals and Manners.

Martineau had struggled from childhood with ill health, and sensory loss. She had become almost completely deaf by the age of 20, and used an ear trumpet, which American author Nathaniel Hawthorne recalled ‘as an organ of intelligence and sympathy… a sensitive part of her, like the feelers of some insects’. Toward the end of the 1830s, she suffered a breakdown in health – likely caused by an ovarian cyst – and moved to Newcastle to be close to her doctor. In 1844 she published Life in the Sickroom, in the first lines of which she wrote:

The sick-room becomes the scene of intense convictions; and among these, none, it seems to me, is more distinct and powerful than that of the permanent nature of good, and the transient nature of evil… And how is this?… Because the good is indissolubly connected with ideas — with the unseen realities which are indestructible.

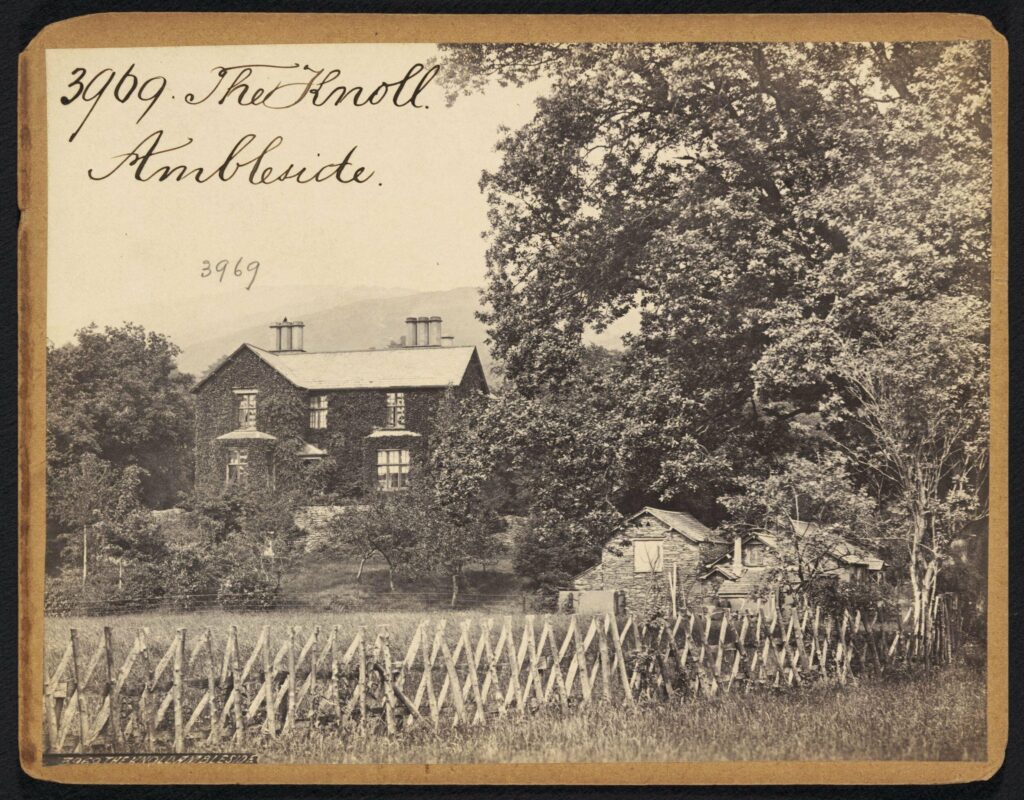

The following year, Martineau settled in the Lake District, where in 1846 she moved into The Knoll, in Ambleside. There, she entertained a host of friends and admirers, continued to write, and devoted time and funds to charitable causes.

In 1851, she published Letters on the Laws of Man’s Nature and Development: a collection of letters between Martineau and her ‘mesmeric advisor’ Henry George Atkinson. While containing some of her most resoundingly clear rejections of religion, the letters also stated her faith in mesmerism, a pseudoscientific system of healing which divided 19th century opinion. Her dismissal of theology in the Letters was unequivocal:

There is no theory of a God, of an author of Nature, of an origin of the universe, which is not utterly repugnant to my faculties; which is not (to my feelings) so irreverent as to make me blush; so misleading as to make me mourn.

In the same year, Martineau was introduced to the positivist philosophies of Auguste Comte, who offered a secular ‘religion of humanity’ based on science and human achievement. In 1853, she published her attentively abridged translation of his writings as The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, which became hugely influential in introducing these ideas to the English-speaking world. The Victorian age had brought with it a significant shift in scientific understanding, pulling the rug out from under the religious convictions of many. Aware of this, Martineau acknowledged:

We are living in a remarkable time, when the conflict of opinions renders a firm foundation of knowledge indispensable, not only to our intellectual, moral, and social progress, but to our holding such ground as we have gained from former ages.

Although not uncritical in her acceptance of Comte’s ideas (rejecting, for example, the rigid hierarchies and subordination of women), she published the work in the firm belief that:

When this exposition of Positive Philosophy unfolds itself in order before their eyes, they will… find there at least a resting-place for their thought — a rallying-point of their scattered speculations, — and possibly an immoveable basis for their intellectual and moral convictions.

In 1855, Martineau was again beset by illness. A letter from suffragist and abolitionist Parker Pillsbury, dated 15 February and printed in abolitionist paper The Liberator, reported:

Miss Martineau is in the last stages of life. The affection of the heart, from which she has long suffered, seems almost to have reached its crisis — a crisis always fatal.

Though she was not to die for another two decades, she remained severely restricted by ill health. Having been convinced of her life-threatening illness, she penned her autobiography (only posthumously published) in three months, still considered to be a remarkable work of self examination.

Harriet Martineau died on 27 June 1876 at home in Ambleside. She was buried on 1 July in the family plot in the general cemetery, Key Hill, Birmingham.

What an insult it is to our best moral faculties to hold over us the promises and threats of heaven and hell, as if there were nothing in us higher than selfish hope and fear!

Harriet Martineau, Letters on the laws of man’s nature and development (1851)

Harriet Martineau, in her endless capacity for self-reflection, curiosity, observation, and inquiry, was a consummate humanist and a remarkable writer. In letting go of religion, she embraced an empowering sense of goodness for its own sake, and recognised that life was no less precious for being transient. Martineau placed her trust in what could be discovered through reason, and was fearless in openly expressing her unbelief. Of her early devoutness, she wrote:

I look back with a kind of horror, as well as deep pity, on myself, in the days when I thought it my duty to cultivate (against nature) an anxious solicitude about my own “salvation,” — my own future spiritual welfare. I should now think this as bad as engrossing myself with storing up means of prosperity while my brother had need. How sweet it is to be loose from all such solicitude, and to let one’s best nature have its free play from hour to hour!

Not only did Martineau play a leading role in spreading the secular philosophies of Auguste Comte in the UK, she exemplified in her own life a celebratory, life affirming humanism, the expression of which still resonates today.

How far happier it is to see — how much wiser to admit — that we know nothing what- ever about the matter! … how well it would be for us to set our minds free altogether, — to open them wide to evidence of what is true and what is not!

HARRIET MARTINEAU, LETTERS ON THE LAWS OF MAN’S NATURE AND DEVELOPMENT (1851)

Main image: Harriet Martineau by George Richmond, 1849 © National Portrait Gallery, London

A wide-ranging Humanism will always seek to extend to more and more people, through education and opportunity, the enrichment of […]

Essentially, I am interested in this world, in this life, not in some other world or a future life. Whether […]

We have the faculties for gaining knowledge; and Rationalism will always maintain that we are at liberty to use them […]

I don’t understand people panicking about death. It’s inevitable. I’m an atheist; you’d think it would make it worse, but […]