The time has arrived for us humans to stop leaning on ideas for a creator god; we should get down to solve our own problems by cooperation, sharing, caring for the planet and one another… We have a few years to make what we can of our lives on this fascinating little planet, earth. We need others; others need us. Together we can achieve significance and fulfilment.

James Hemming, ‘How I Became an Atheist’ for the BBC World Service

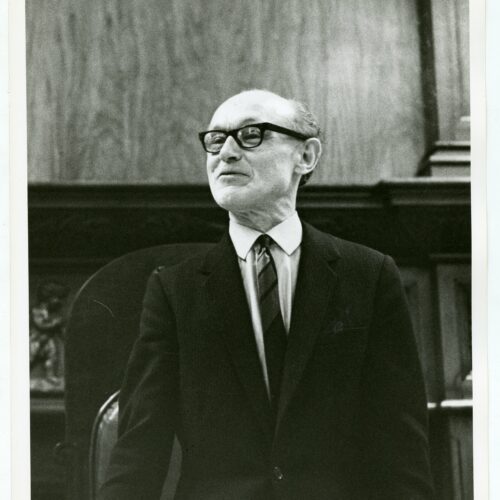

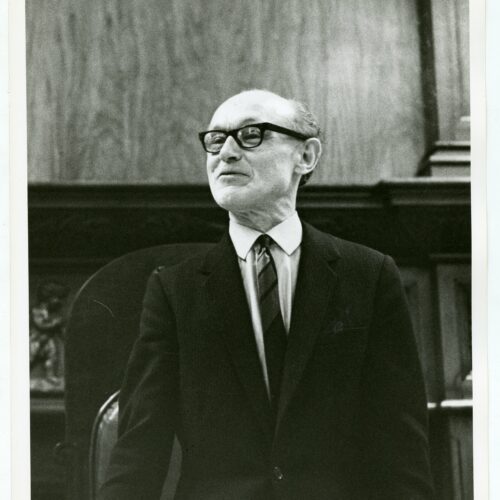

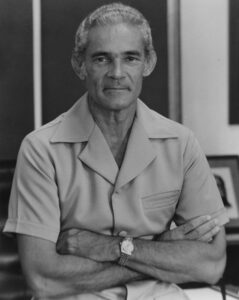

Dr James Hemming was a psychologist, educationist, and humanist, who played an integral role in the life of the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK), and the development of values now central to the organisation. A member of the BHA from its formation, its President 1977–80, and a longtime member of its Executive Committee, Hemming was actively involved in numerous campaigns and initiatives. He was a pioneer of interfaith dialogue, placing cooperation and compassion at the heart of his personal and professional lives, and a prominent advocate of moral education. Remembered for his kindness, warmth, and positivity, his position was not one born of naivety. Instead, it was based firmly on a humanist commitment to looking squarely at the world as it is, and working for ways to make it better.

And in life, the meaning comes in living, as wholly as we can, as abundantly as we can, as bravely as we can, here and now, sharing the experience with others, caring for others as we care for ourselves, and accepting our responsibility for leaving the world better than we found it. There is meaning enough in this to last a lifetime. The old man who enjoys the open air while planting a tree for his great-grandchildren to play under goes to bed content, and rounds off his good day with quiet sleep.

James Hemming, Individual Morality (1969)

James Hemming was born in Stalybridge, Cheshire, on 9 September 1909, the son of a clergyman. His father, Ebenezer Hemming, held regular meetings with other religious figures from the local area, during which they would discuss and debate Church teachings, and in which the young Hemming was allowed to take part. His father’s early encouragement of open dialogue and honest questioning was formative, becoming central to Hemming’s later work, and to the development of his humanism. His early schooling was mixed, and ended at sixteen, but he earned his BA through a correspondence course at Birkbeck College, London, and eventually gained a PhD. Hemming went into teaching, working at schools in Bristol, Bournemouth, and Middlesex. He met his wife, Kay, while both were teachers at Isleworth Grammar School, and the two had a long and happy marriage.

Hemming’s central focus on matters of education, and efforts toward its reform, began while teaching and continued throughout his career. His publications, and public advocacy, advanced a reasoned, compassionate approach to education and towards young people, from efforts to abolish use of the cane in schools, to calls for comprehensive sex and relationships education. Hemming believed firmly in the role of education as preparation for life, not merely as a means of passing exams, and decried a system which left many children feeling like failures. He argued instead for a curriculum which would promote confidence, capability, and informed citizenship in young people.

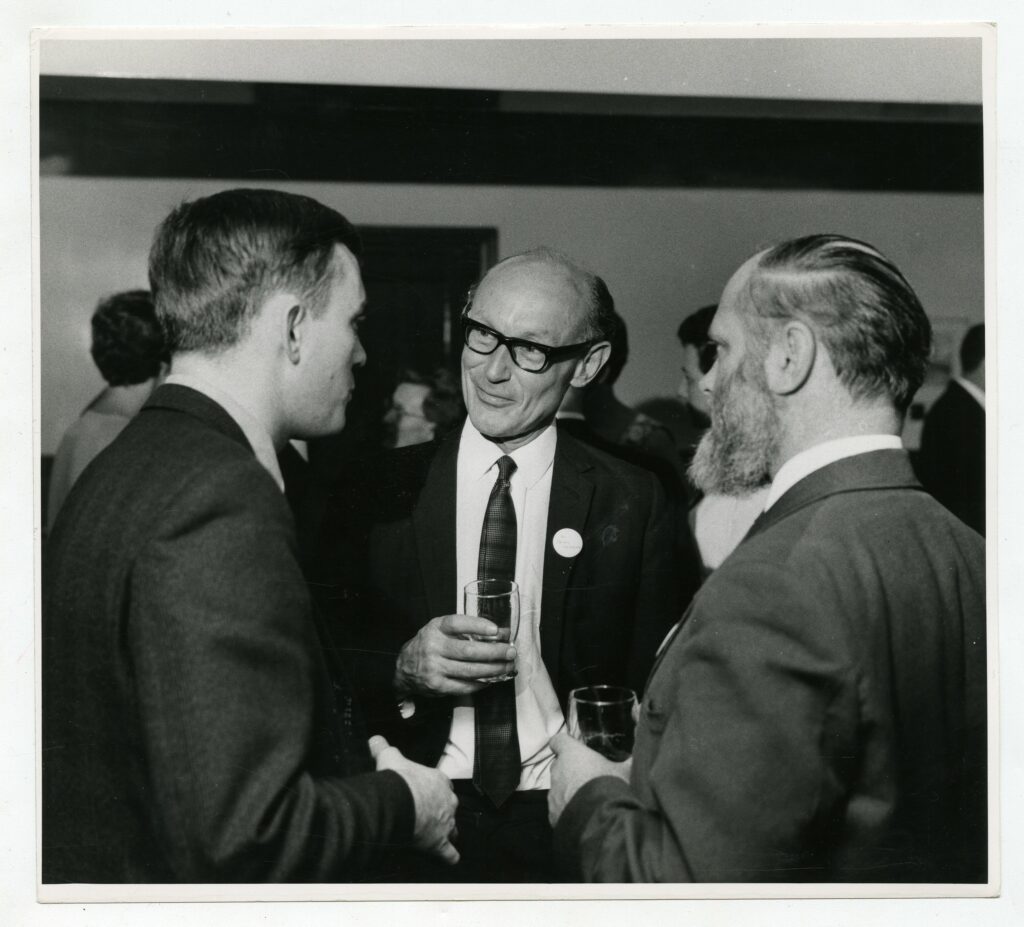

Hemming was a member of the British Humanist Association from its creation (as a partnership between the Ethical Union and RPA) in 1963. He spent many years on its Executive Committee, became its President 1977-80, and remained a Vice President until his death. From the 1960s to the 1990s, he played a key role on the BHA’s Education Committee, seeking the equal and accurate representation of non-religious lifestances in the curriculum, and was a humanist representative on the Religious Education Council of England and Wales during the 1980s and 1990s. A pioneer of new initiatives in civic education, he was actively involved in the Campaign for Moral Education, and central to the creation and success of the Social Morality Council (later the Norham Foundation), bringing diverse viewpoints together for the discussion of moral issues.

Hemming was a persuasive and eloquent advocate of rational, realistic, and appropriate sex and relationships education. In 1960, as a witness for the defence in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover obscenity trial, he argued for the book’s merit as an antidote to the dehumanising and shallow depictions of sex to which so many were typically exposed, lauding the presentation of ‘tenderness, compassion, and an enduring relationship’. Fellow humanist E.M. Forster had also testified to the novel’s ‘serious inquiry into sexual relationships’, as well as to its literary merit. In 1971, Hemming authored a pamphlet for the Royal Society for Health, entitled Sex Education for School Children, and in 1987 laid out his beliefs for the BBC:

What is necessary for children is that they should have a complete, profound understanding of the full range of human sexuality, without any special bias being put on here and there, or trying to sell one particular line or another. Let them know honestly. If we don’t tell them what the facts are through education, they will pick up distorted and garbled views from the mass media and their friends. That is the choice: whether we give children the information they need to grow up as mature citizens, or whether we deliberately seem to be withholding part of it because it’s “wicked”.

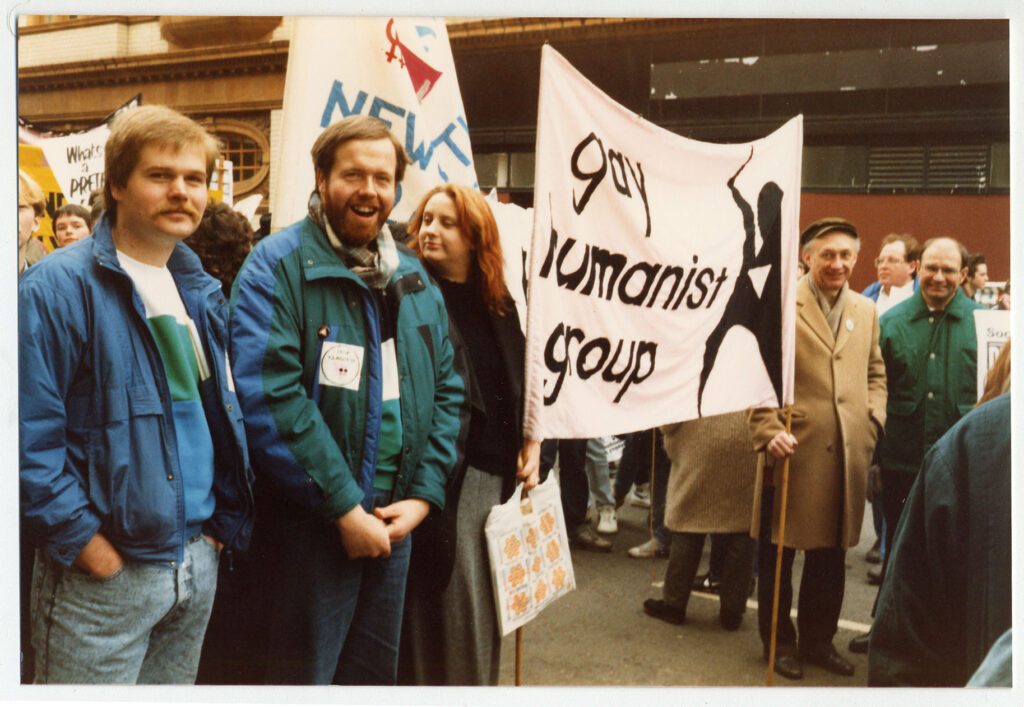

Hemming was an active supporter of LGBTQ rights, including as a vocal challenger of the notorious Section 28 ban on the ‘promotion’ of homosexuality in schools. He was a Vice President of the Gay and Lesbian Humanist Association (now LGBT Humanists), as well as of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality. In 1974, he was a signatory on a letter from Vice Presidents of the latter, rebuking Tunbridge Wells Council for refusing to let its Assembly Hall for a classical concert organised by the CHE. The letter, whose other signatories included prominent humanists Brigid Brophy and George Melly, contained the reminder that ‘democracy depends on reciprocal tolerance and on the majority’s not cutting off harmless minorities from lawful means of self-expression’.

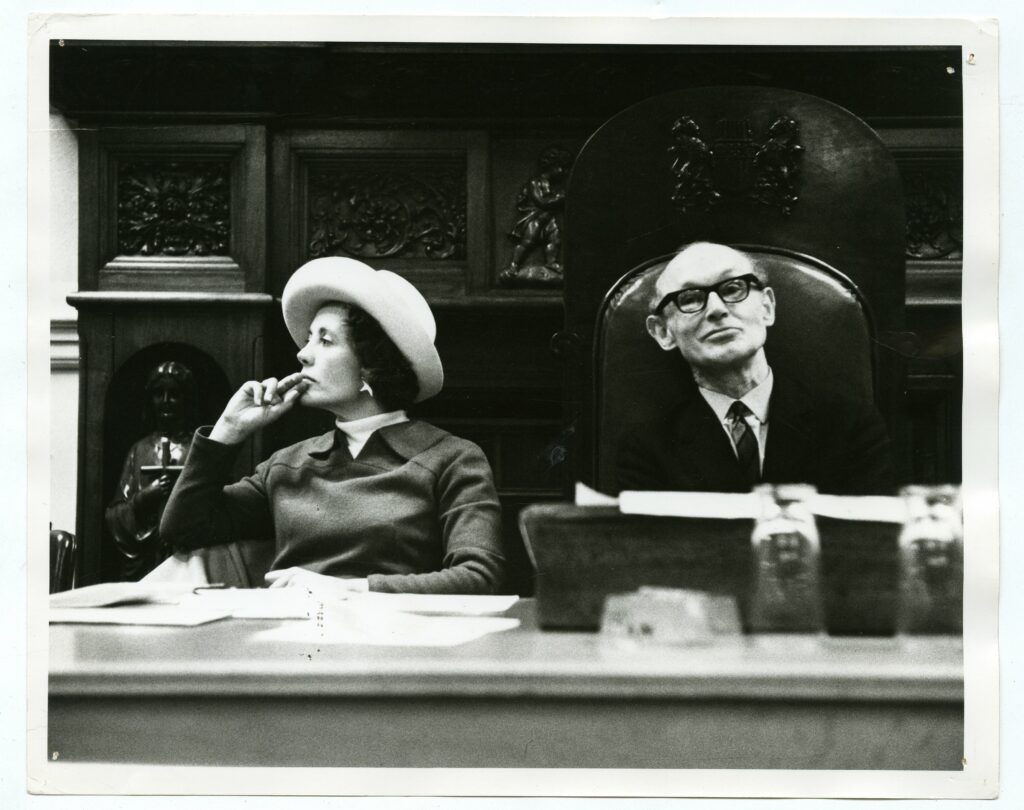

Hemming’s writing, his activism, his work, and his daily life, were guided by firmly rooted humanist convictions: centred on rationality, kindness, and cooperation. The Sunday Times described his intention as being ‘to cut the cackle and address himself to common sense,’ concentrating ‘on life as it is lived.’ As well as in his writing, this was embodied in Hemming’s longtime presence on the panel of the BBC’s advice programme If You Think You’ve Got Problems, alongside his close friend (and successor as BHA President), Claire Rayner.

In 1999, celebrating his 90th birthday at Conway Hall, Hemming delivered a characteristically hopeful, and quintessentially humanist, speech, titled ‘What’s the World Coming To?’ In it, he emphasised the responsibility – and possibility – of humankind, echoing the essence of a slogan he had playfully offered up years earlier: ‘Caring, Cooperation, and Cosmic Responsibility’. In a clarion call for for environmental, moral, and thoughtful living, he said:

We humans now have the power to destroy life on Earth as well as to bring it to fulfilment. This is now the primary global issue. How are we to create a caring and collaborative world? This needs a shared philosophy to sustain it. This is where Humanism comes into world affairs. The ‘one world’ religious myths that Man has depended upon for thousands of years will inevitably lose their grip in the 2Ist century. As the God-myths fade something other than cults, or escapism, is called for. That something is a caring, creative and coherent Humanism, dedicated to carrying life forward on our beautiful little planet.

James Hemming died on 25 December 2007, at the age of 98. A simple ceremony accompanied his cremation at South West Middlesex Crematorium, Hanworth, and a memorial meeting to celebrate his life was held at Conway Hall in April 2008.

If we act, we influence; if we don’t act, we influence; if we speak, we influence; if we stay silent, we also influence. We influence by the fact of being alive. There is no way of getting out from under this responsibility. We use it creatively when we strive to choose with sincerity, imagination, vision, and compassion.

James Hemming, Individual Morality

James Hemming was a major figure in the humanist movement from the 1960s until his death, and his influence on key areas of practise and policy is still felt in the work of Humanists UK today. At his memorial meeting in 2008, John White reminded those gathered of Hemming’s trailblazing work in fostering dialogue and building the BHA’s reputation:

You will know that today the BHA is represented on high-level Government advisory and policy-making bodies. We are there because the BHA has a reputation for responsible, constructive dialogue. The foundations of that reputation were laid by the pioneering work of James Hemming.

In every aspect of his life, Hemming embodied the humanist philosophy he advocated. Patience, compassion, and personal warmth defined his work in education, and underpinned his success in encouraging dialogue between people of diverse beliefs and attitudes. He stood firmly for a rational, empathetic approach to all things, whether in literature, law, or learning; challenging blasphemy laws, defending LGBTQ rights, and advocating tirelessly for practical, inclusive moral education. Hemming led a long and active life, and proved without question that one can be good without god. As he put it in a talk given in 1993:

… the task of those who seek to be honest is to replace myth with truth, to make a fresh start in the context of the exciting contemporary knowledge about our human situation. As for a slogan? Cultural change always needs a slogan to encapsulate briefly the essential ideas. It is hard to find an equally cogent one for our times as the ones mentioned above, but perhaps something like: ‘Caring, Cooperation, and Cosmic Responsibility’. Or, more colloquially, ‘Let’s build a planet of which we can be proud.’

I like life with its mysteries. I don’t need my imponderables filled in for me. Michael Manley quoted by Rachel […]

But this much is certain, that, taking the world as we find it, sympathy, plus a modicum of common sense […]

I have no desire… to bring the religion or the laws of this country into contempt, although I am a […]

No law can be effective which has not behind it the sanction of the people. Dorothy Thurtle, quoted by David […]