Purity of life, sincerity of action, obedience to law, love of our fellow creatures, all those qualities which ennoble life are the stronghold of the Agnostic.

Julia Stephen, ‘Agnostic Women’ (1880)

Julia Stephen was a philanthropist, writer, and celebrated beauty, whose defence of the ‘agnostic woman’ – though unpublished in her lifetime – presented a powerful argument for the right of women to religious scepticism. Julia, herself an agnostic, was first drawn to her future husband Leslie Stephen on account of his own writings on non-belief. Their marriage of minds would bring Virginia Woolf, another remarkable humanist, into the world, and provides a rich vision of 19th century humanist thought and deed.

…whether as some believe the night is a prelude to the glorious day of Heaven or the deepest night of Hell… or whether annihilation or transmigration be our doom, we have still our day on earth. It is that day in which we have to work with all our might.

Julia Stephen, ‘Agnostic Women’ (1880)

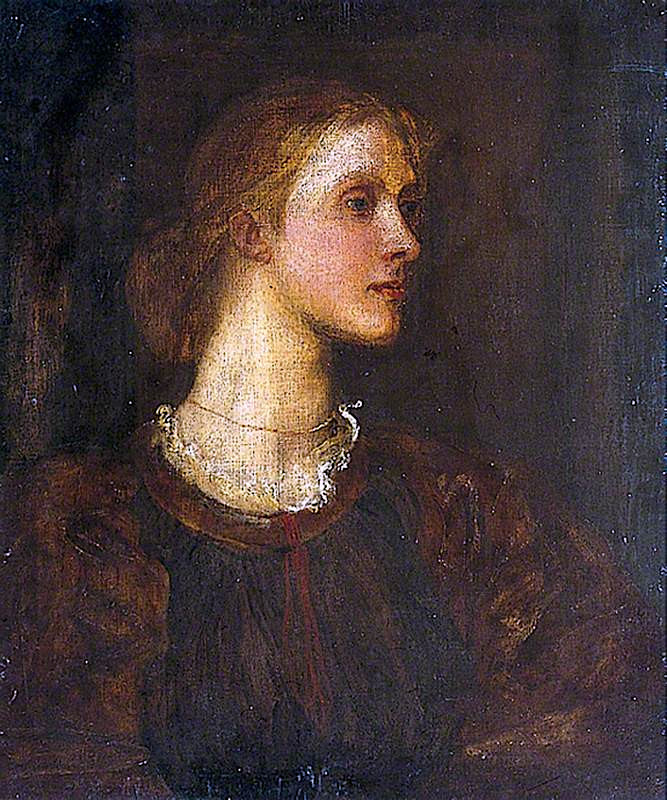

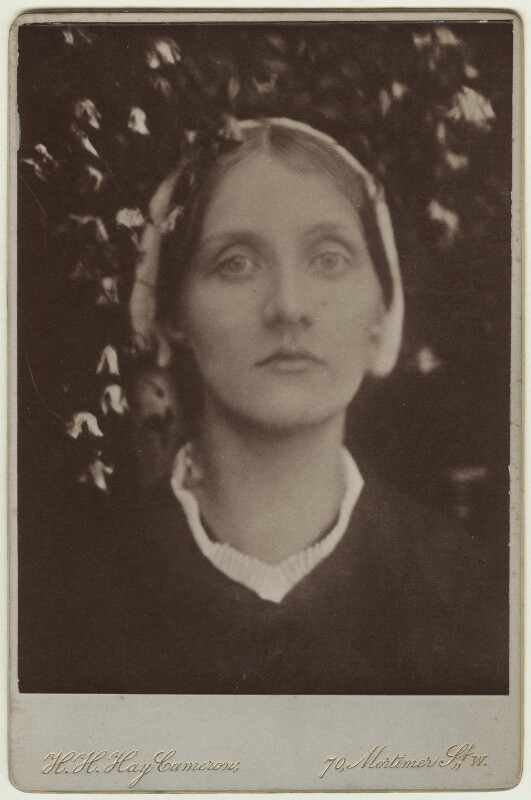

Julia Prinsep Jackson was born on 7 February 1846 in Calcutta, India to Dr John Jackson and Maria (née Pattle). Her maternal aunt was pioneering photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who took many striking photographs of her niece as a young woman. Returning to England with her mother in 1848, Julia Jackson was educated at home, and raised in a vibrant and cultured circle. She modelled for Pre-Raphaelite artists including Edward Burne-Jones, George Frederic Watts, and William Holman Hunt – the last of whom proposed marriage. Her first husband, however, was Herbert Duckworth. With him she had three children, and enjoyed a happy marriage. His death in 1870 devastated her, but confirmed both an enduring empathy with the suffering of others, and a firm rejection of Christianity.

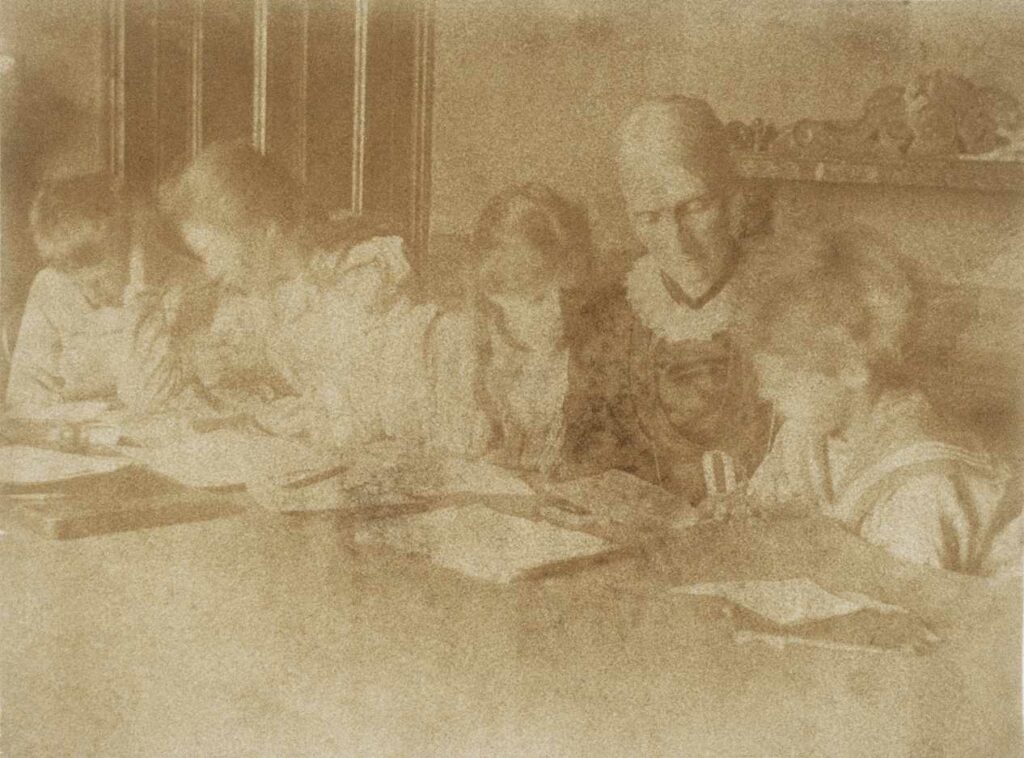

In 1878, she married Leslie Stephen, himself a widower and for a number of years a close friend. Leslie Stephen was a prominent figure in the early Ethical movement, and a longtime President of the West London Ethical Society. It was his writings on agnosticism which had first appealed to Julia and, as her 1880 essay demonstrates, she was eloquent in her own unbelief. The couple had four children together: Vanessa, Julian Thoby, Adeline Virginia, and Adrian.

In 1880, Julia Stephen was prompted to write a heartfelt defence of the agnostic woman, in response to ‘a kindly but condemnatory article’ by Bertha Lathbury in The Nineteenth Century. Lathbury had suggested that in losing their faith, women would lose those caring qualities which defined them. Or, as Stephen put it in her essay:

From the moment they discover that there are things beyond their credence and that they cannot therefore belong to any known sect, they shut the door on hope, love, work except of the driest and most unsatisfying kind.

In a powerful riposte, Stephen argued that ‘women who give up the faith in which they have been educated do so from a feeling that it no longer satisfies them’ (not, she emphasised, in imitation of men). At this point, though ‘they are content to confess not their belief but their ignorance’, they nevertheless remain capable of empathy, philanthropy, and active care for others. Stephen laid out a distinctly humanist philosophy, focused on helping others in this world, with no hope of afterlife or divine reward. In nursing, she wrote:

We are not thinking that we shall gain a glorious immortality, that we shall be crowned as saints because we have helped our fellow creatures… We are bound to these sufferers by the tie of sisterhood and while life lasts we will help, soothe, and, if we can, love them. Pity has no creed, suffering no limits.

Julia Stephen herself was noted for her profound selflessness: nursing her own parents until their deaths, providing endless reassurance to her husband, supporting family and friends, and travelling throughout London to visit hospitals and workhouses. Perhaps surprisingly, she was no advocate of women’s suffrage, believing wholeheartedly in the separate spheres of men and women. She did, though, argue vehemently for the right of women to exercise their intellect, and to reach their own conclusions in matters of religion. Drawing her 1880 essay to a close, Stephen implored:

…in the acceptance or rejection of a creed let the woman be judged as the man. In this, if in this alone, man and woman have equal rights and, while crediting men with courage and sincerity, do not let us deny these qualities to each other.

Julia Stephen died at home in London on 5 May 1895, a victim of heart failure hastened by influenza. She was buried at Highgate Cemetery.

Julia’s life, untimely death, and her loving relationship to her daughter have long been of profound interest to scholars of Virginia Woolf. The critic Ellen Roseman describes Julia as a ‘constant’ in Woolf’s writing. She is represented in some form across all of her daughter’s novels, but most prominently in The Voyage Out (1915), Jacob’s Room (1922), and To the Lighthouse (1927). Deeply haunted by the death of her mother, Virginia chose to preserve her in a kind of literary immortality.

Julia’s own writing provides an important window into 19th century humanist thought. Though by no means the only woman to express religious doubt in Victorian England, Julia Stephen’s spirited defence of agnosticism has been relatively under-appreciated in the canon of humanist writing. Her essay serves as a reminder that an agnostic outlook on life was far more common in the 19th century than is often acknowledged, as well as highlighting the ongoing prejudice faced by women who strayed from a stereotype of religious piety and meekness in the late Victorian period. In emphasising the worldly, human impulses behind empathy and altruism, Julia Stephen made a powerful case for humanism. And, as Sybil Oldfield has written, ‘it is strange but true that had not Leslie Stephen and Julia Duckworth found a bond in atheism, there would have been no Virginia Woolf.’

‘A Child of Two Atheists – Virginia Woolf’s Humanism’ by Sybil Oldfield in the Ethical Record, Vol. 116, No. 7

Julia Duckworth Stephen: Stories for Children, Essays for Adults eds., Diane F. Gillespie and Elizabeth Steele (1987)

Julia Stephen | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Julia Prinsep Stephen (née Jackson, formerly Mrs Duckworth) | National Portrait Gallery

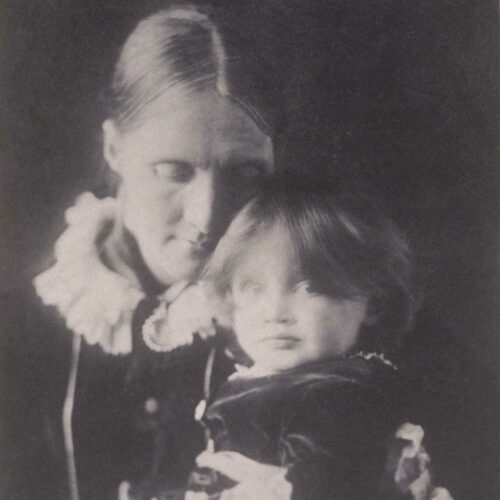

Main image: Julia Stephen with Virginia on her lap by Henry H.H. Cameron, 1884

The London Ethical Society was the UK’s first, founded in 1886 to pursue ‘a rational conception of human good’: establishing […]

Against the militarist totalitarian state, I have striven. For the freedom of the human spirit to develop under the kindly […]

Elizabeth Swann was an active and devoted champion of liberal and progressive causes alongside her husband, Liberal MP Charles Swann. […]

Founded in 1905 by the prolific but largely unremembered writer Richard Dimsdale Stocker, the Brighton and Hove Ethical Society – […]