Belief in the power of man to choose his direction of change: this is the creed of the future, and it will soon come to be the distinctive mark of the essentially modern thinker.

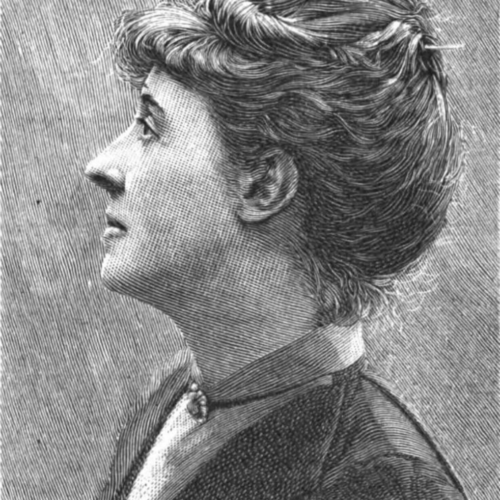

Mona Caird, ‘The Future of the Home’ in The Morality of Marriage and other essays on the status and destiny of woman (1897)

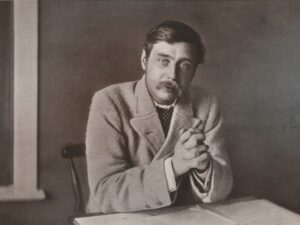

Mona Caird was an English novelist and essayist whose controversial views on marriage sparked outrage in the late 19th century. A freethinker and feminist, Caird’s humanist values and feminist writings contributed to the advancement of the ‘New Woman’: an ideal that emerged in the late 19th century referring to independent–minded women seeking radical change. Through her writings and associations, she campaigned for myriad causes, including the improved status of women, the protection of animals, pacifism, press freedom, and international cooperation – concerns shared by many humanists then and today. Notably, she also challenged eugenic principles, and since the 1990s has come to be increasingly recognised as an original and influential thinker.

I feel that the spirit which would bring justice and relief to the suffering among human beings is really the same as that which would hasten the salvation of the tortured among animals.

Mona Caird, Vivisection (1895)

Alice Mona Alison was born in Ryde, Isle of Wight in 1854, the elder daughter of inventor John Alison of Midlothian, Scotland, and Matilda Hector, who was born in Schleswig-Holstein, at the time part of Denmark. In December 1877, she married James Alexander Henryson–Caird. While he lived mainly on his estate in Dumfries and Galloway, she spent much time in London and abroad. She mixed with literary people, including Thomas Hardy, who admired her work, and educated herself in humanities and science. The Cairds had one child, a son, born on 22 March 1884 and named Alister James.

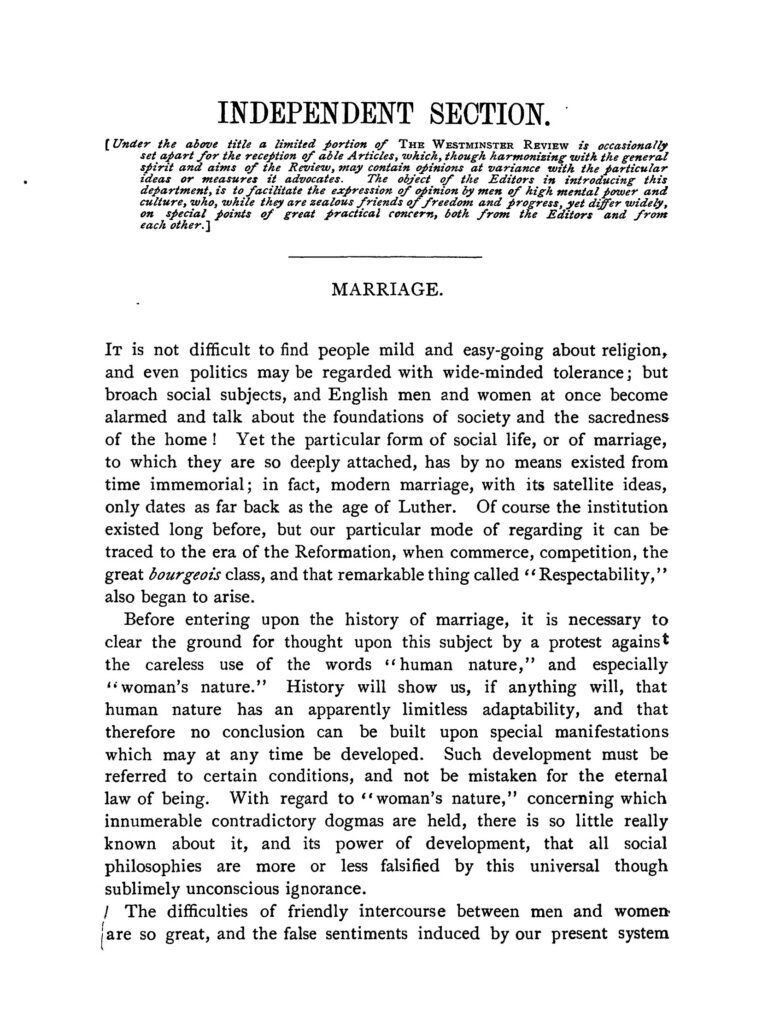

Mona Caird became involved in various activities supporting women’s rights, and contributing articles to a number of influential magazines, including the radical quarterly Westminster Review and the Fortnightly Review. The 1888 article ‘Marriage’, criticising marriage for limiting and subordinating women, brought her widespread recognition and propelled the ‘New Woman’ into the public consciousness. The Daily Telegraph, which initiated an open correspondence, received 27000 letters in response. Caird’s article called for equality between partners, as well as identifying patriarchy as historically contingent rather than God-ordained. Like her contemporary, Zona Vallance, she saw patriarchal attitudes towards women and marriage as outdated remnants of an earlier time, ripe for reconsideration in the light of new understandings. Going further than many other women activists of the time, Caird also challenged the Victorian ideal of self-sacrificing motherhood, viewing this too as a tool of oppression.

Caird challenged contemporary eugenicists, defended women’s right to use birth control, and argued with firm humanist values that the human race would evolve not through conflict and competition, but with the cultivation of compassion, and the fostering of equality, freedom, and human rights. Since the 1990s, feminist scholarship has praised Caird’s achievements, referencing her work in relation to contemporary debates on gender and sexuality. Scholar Ann Heilmann has described Caird’s calls for societal revolution as rooted in a ‘politics of caring’ and an ‘ethics of responsibility’.

Caird recognised the importance of preserving the dignity of individuals and treating them with fairness and respect, applying these values outside of the scope of the human race. She highlighted parallels between the treatment of animals and women in the Victorian era, leading her to take on an anti-vivisectionist stance. She became involved in the animal protection movement, vehemently challenging support for vivisection on the grounds that it advances medicine. For a short time, Caird was President of the Independent Anti-Vivisection League and it is believed that this commitment estranged her from both her husband and son, who were fond of hunting and fishing. She published four pamphlets on the subject, in which she provided arguments against man having the right to exercise absolute power over animals. Caird hoped for the end of patriarchy and the beginning of a civilisation based upon a respect for human and non-human creatures alike.

Mona Caird died at home in London on 4 February 1932. Her short obituary in The Times remembered her as:

actuated in thought, word, and deed by a fine sense of loyalty, of honour, and of through-and-through integrity. These fundamental characteristics were illuminated by lambent wit and a keen sense of humour—to the last she would laugh with the zest of a child. Endowed with a ratiocinative intellect, combined with a remarkably retentive memory, she was a keen student of science, sociology, history, and philosophy. She was prominent and effective among the pioneer champions of the “woman’s movement,” but declined to join the militant section.

‘Mrs. Mona Caird’ in The Times, 5 February 1932

Were human ideas as fixed as we suppose, or instincts as immutable, progress would be an impossibility… The cause of national inertia appears to be the restrictive effect of a religion, or a changeless order of ideas, which makes a spell-bound people, inaccessible to new views of life.

Mona Caird, ‘Early History of the Family’ in The Morality of Marriage and other essays on the status and destiny of woman (1897)

Mona Caird is remembered today as a bold and progressive thinker, who challenged many of the orthodoxies of her time and stood firmly for the equal rights of women. She contributed to humanist publications, such as South Place Ethical Society’s journal, and championed causes long central to humanist campaigning, including birth control, divorce law reform, and freedom of the press. Above all, her vision for a reimagined society rooted in compassion, responsibility, and freedom, was a profoundly humanist one.

Mona Caird by Lisa Surridge | Oxford Bibliographies

Caird [née Alison], (Alice) Mona | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Ann Heilmann, ‘Mona Caird (1854-1932): wild woman, new woman, and early radical feminist critic of marriage and motherhood’ in Women’s History Review 5:1, 67-95 (1996)

By Laura McGarrick

…the only universal truths which exist are the fundamental laws of the mind. Philosophy, then, which is the science of […]

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]

What primarily unites Humanists is not a set of propositions to be believed but moral values to be freely chosen… […]

More science is needed, more interchange and more co-ordination. Act to that end. This is my philosophy of action; this […]