Its aim will be to secularise education and make moral training the chief aim of the school life. A great public meeting will take place at St. Martin’s Town Hall, Charing Cross… to which all Ethicals, Freethinkers, and liberal-minded people in general are invited.

Notice of the first meeting of the Moral Instruction League in The Literary Guide, 1 November 1897

From the origins of the Ethical movement in the UK, education sat central to its aims. The Moral Instruction League was formed by a group of active members of the Union of Ethical Societies, their object being ‘to substitute systematic non-theological moral instruction for the present religious teaching in all State schools, and to make character the chief aim of school life.’ The League’s inaugural meeting was held on 7 December 1897, and for almost two decades it was a driving force in the promotion and development of secular moral education on a national and international scale. The ongoing work of Humanists UK in the areas of compulsory collective worship, faith schools, religious instruction, and the representation of non-religious worldviews, has its origins in the efforts of the Moral Instruction League, formed well over a century ago.

One of the League’s first actions was to challenge the notion that all parents and teachers were satisfied with the existing provision of religious education in schools. A petition was raised, seeking to demonstrate the falsity of such an assumption. It read:

The statement having been frequently made at public meetings and circulated in the daily Press that all the parents of Board School children are satisfied with the religious teaching now given in the Board Schools of London, we, the undersigned, parents of such children, in order to prove to the Board the falsity of that statement, and to help towards the introduction of moral teaching which shall make no appeal to supernatural or superhuman motives, do hereby protest that in general such motives are not suitable to the understanding and character of children, and are particularly out of place when taught in State Schools, which are maintained at the cost of citizens of every creed and of no creed.

In place of traditional Bible lessons, specially trained teachers would deliver sessions in which ‘the sense of responsibility, sympathy with all sentient beings, intellectual honesty, the spirit of liberty, courage, self-respect, and the other highest qualities of manhood would be systematically cultivated and strengthened.’ Among resolutions passed at a special meeting in 1898, was the agreement that the Bible comes under the head of general literature, as a source of illustrations and maxims for moral lessons.’

In 1899, the petition was presented by a deputation to the school board, showing ‘that the supposition that parents are pleased with the present Bible teaching is quite unfounded in fact’: their 513 signatories representing 1,086 scholars. This deputation included feminist writer Zona Vallance (inaugural Honorary Secretary of both the Union of Ethical Societies and the Moral Instruction League), future Prime Minister James Ramsay Macdonald, Labour politician William Sanders, Elisabeth Cobb (wife of Liberal MP Henry Peyton Cobb), George Augustus Smith, and Stanton Coit as the spokesman, and was heard on 23 June by the School Management Committee, of which Graham Wallas (a future President of the Ethical Union) was Chairman. They were thanked, and their objections noted, but the board declined to make alterations to the present system.

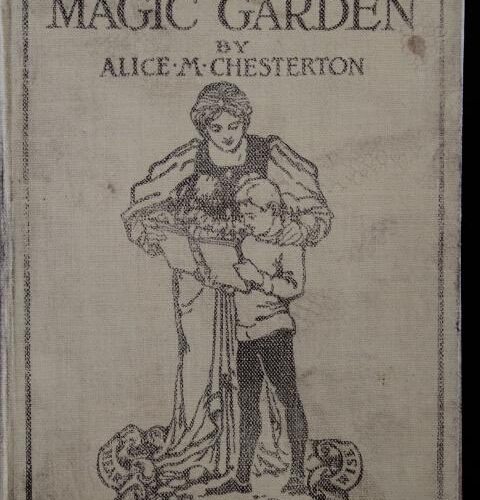

The League nonetheless continued their efforts. In 1900 a questionnaire sent to candidates for the London School Board elections asked whether they would favour replacing religious teaching with non-theological moral instruction, or support parents being offered the choice to withdraw children from religious lessons and be provided with moral instruction instead. To this second (compromising) proposal, of 37 responses, 10 were affirmative, 20 negative, and 7 doubtful. The League also sent information for candidates in provincial School Board elections. In the same year, F.J. Gould stood for election to the Leicester School Board on the platform of secular education, ultimately coming second among 15 candidates. In Plymouth, Arthur T. Grindley, who advocated ‘Secular Education – the principles of Truth, Justice, and Moral Courage’ be taught in board schools, was elected unopposed.

In subsequent years, the League expanded their efforts to effect change in provincial schools. In 1902, largely through the efforts of Gould (then on the School Board), half an hour per week of non-theological moral instruction was being given in Leicester schools, and the following year Bradford followed suit.

School boards were abolished by the Education Act 1902, and responsibility for schools shifted to local authorities. The League too shifted gears and ramped up their efforts, sending – in 1904 – circulars and moral instruction literature to 7000 members of Education Committees and over 300 of their Secretaries. The same year, they reported their success in achieving provision for moral instruction in schools across the country, with eleven local authorities offering – or planning to offer – systematic moral education. The following year, this was 25, and in 1906, 34.

During these years, the League also held well-attended public meetings, and corresponded regularly with the press. They influenced public opinion as well as official policy, with the Education Minister Augustine Birrell announcing, in 1906, his belief that

rationally conducted, it [moral instruction] can be made a very live and a very real thing. I do not think for a moment that morality can only be taught on a theological basis. I am quite sure that it can be taught, with spirit and with force, apart from such a basis.

In July of that year, the Code of Regulations for Public Elementary Schools made specific provision for moral instruction, whether ‘incidental, occasional’ and ‘in the ordinary routine of lessons’, or ‘systematically and as a course of graduated instruction’. Unfortunately, this ‘or’ allowed many to largely circumvent the provision, although from those numerous schools who did introduce moral instruction came a range of glowing reports.

In 1908, the League organised the First International Moral Education Congress, held in London 25-29 September. It brought together delegates from across the world to discuss non-theological moral instruction, and for the presentation and discussion of a vast collection of papers. Its patrons included the Education Ministers of Barbados, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, England, France, Greece, Holland, Honduras, India, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Mexico, Romania, Russia, Spain, Turkey, and the US, as well as those from Canadian provinces and Australian states.

In 1910, F.J. Gould was appointed Lecturer and Demonstrator for the League. He presented before teacher training colleges, educational societies, the National Union of Teachers, and on behalf of the Rationalist Press Association. As well as addressing groups around the UK, Gould undertook a tour of the US, under the auspices of the American Ethical Union. He delivered a total forty-six demonstration Moral Lessons. The organiser of the tour, educator, feminist, and Unitarian minister Anna Garlin Spencer, stated her belief that Gould’s method was more effective ‘than anything that has yet been done in this country’. In 1912, he sailed for Bombay, and toured the region’s major towns, ‘demonstrating and lecturing’. In 1913, he returned to America and over the course of seven months visited 32 cities, delivered 292 lessons and addresses, and met nearly 30,000 people.

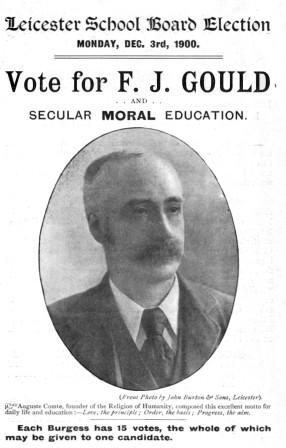

The League also published widely, and distributed its literature to educators and authorities throughout the country, and across the world. The League published a syllabus for moral instruction in 1902, and later a Graduated Syllabus of Moral and Civic Instruction for Secondary Schools, and Moral Instruction in Elementary Schools in England and Wales, as well as a number of volumes by various authors. Its paper, The Moral Instruction League Quarterly, was published regularly between 1905–1914. Gould’s Moral Instruction: Its Theory and Practice appeared in 1913. A pamphlet called Sex Teaching was also, according to the League, the subject of great interest. The League’s literature was translated into Portuguese and Polish, and its syllabus used in India. Its existence inspired the formation of Moral Instruction Leagues in Germany, France, and India.

The outbreak of the First World War impacted the ongoing efforts of the group, but it continued, becoming the Moral Education League, and, in 1916, the Civic and Moral Education League, reflecting a renewed focus on teaching civic responsibility and ‘high social morality’. In 1919, it became the Civic Education League and moved the following year into Le Play House (65 Belgrave Road, Westminster), the headquarters of the Sociological Society. In 1924, its members formally became those of Le Play House, where a Civics Teaching Department was created, signalling the end of the Moral Instruction League.

In his history of the Ethical movement, Gustav Spiller (himself actively involved with moral instruction) concluded his description of the League by noting:

The Moral Instruction League not only sprang out of the Ethical Movement, but represented one of its outstanding interests. Long before its formation, the American Ethical Societies had laid great stress on systematic moral instruction on a non-theological basis. It was, therefore, natural that Dr. Stanton Coit should have urged from the first the importance and the practicability of such teaching and that the Union of Ethical Societies, under his leadership, should have so largely concentrated on pressing the introduction of that teaching in the country’s elementary schools.

Despite the League’s ultimate winding up, educational efforts continued to remain central to the organised humanist movement, through publications, campaigns, interfaith dialogue, legal challenges, and education committees. Today, Humanists UK provides school resources, humanist speakers, inclusive assemblies, as well as encouraging humanist representation on Standing Advisory Councils for Religious Education (SACREs), and Agreed Syllabus Conferences (ASCs). Education also comprises a large part of Humanists UK’s campaigning work, including around faith schools, the curriculum, PSHE and Sex & Relationships Education, and collective worship.

I think I was born a humanist. John D. Stewart, The Honest Ulsterman, May 1968 John D. Stewart was a […]

Our interest, it seems to me, lies with so much of the past as may serve to guide our actions […]

But however little it conforms or tenders allegiance, no life worth having can be isolated from the lives of others. […]

Our goal must be the good of the whole human society. Henry Noel Brailsford, Olives of Endless Age: being a […]