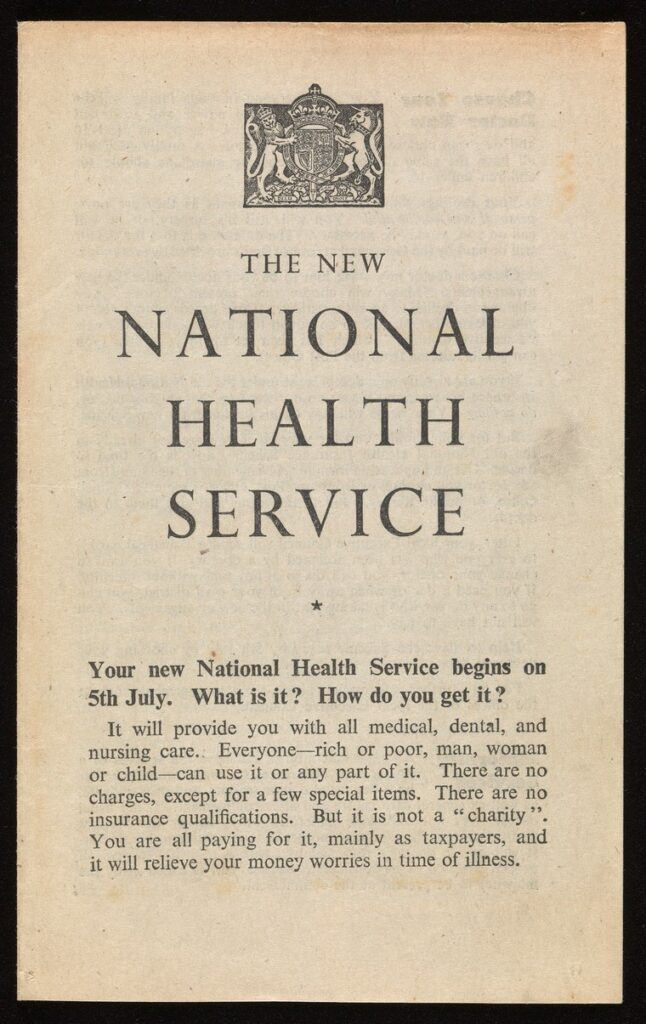

When Nigel Lawson said in 1992 that the National Health Service was the ‘closest thing the English have to a religion’, he may have inadvertently alluded to the very non-religious beginnings of this most treasured institution, the origins of which lie in the bold humanist thinking of three pioneering figures: Aneurin Bevan, Clement Attlee, and William Beveridge. Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan was a proud humanist who, as Minister of Health from 1945-1951, oversaw the NHS’ foundation in 1948. Since its inception the NHS has continued to represent fundamentally humanist values: that scientific advancements can be harnessed for social progress, that people with differing beliefs can cooperate for the common good, and that every human being should be treated with dignity, compassion and respect.

Prior to the Second World War, health care provision for the British people was in bad shape. Much of the system had been established during Victorian times, when hospitals (and workhouse infirmaries) were largely reserved for the poor and were avoided by those who could afford to pay a private doctor. In the early decades of the twentieth century a patchwork system of charitable, public and private healthcare had developed, which saw ‘lady almoners’ interviewing patients at hospitals to decide how their care should be paid for. Some were treated for free, others told to pay, and richer people told they should be moved to a private facility. By the 1930s many local authorities had taken control of hospitals which were run for the benefit of local taxpayers. When war broke out in 1939, the London County Council operated 140 hospitals. This system meant that provision differed hugely across the country and led to terrible health outcomes, including high rates of infant mortality and infectious diseases.

The movement to reform and universalise the health system is often dated back to a 1909 report on the Poor Laws written by the socialist Beatrice Webb. As a sociologist, Webb believed that poverty had underlying causes which could be solved by applying the ‘scientific method’ of her family friend and agnostic philosopher Herbert Spencer. Physicians adopted the cause throughout the 1920s and 1930s, developing a consensus that an integrated health system was needed.

The war proved a turning point for the movement in a number of ways. Government-provided health services had expanded greatly to meet the needs of a country at war. The Emergency Hospital Service was created to care for injured military personnel and air-raid casualties. It was also during this time that the influential Beveridge Report was published (1942), which laid the foundations for the modern welfare state. Its author William Beveridge, who grew up in a humanist household and described himself as agnostic, recommended comprehensive and universal social security, covering housing, employment and education, as well as healthcare.

As the war ended in 1945, Clement Attlee’s newly elected Labour government set about implementing Beveridge’s recommendations and it fell to Nye Bevan to take forward the plans for healthcare. Bevan had grown up in a Welsh mining town and risen through the trade union movement before being elected as an MP in 1929. As a lifelong humanist he saw an innate dignity in his fellow human beings, which was being undermined by chronic issues of poverty and disease. He introduced the National Health Service Act in 1946 but faced several early obstacles, delaying the actual launch of the new service until 1948. GPs were worried that the new service would restrict their income, to the extent that Bevan later claimed he ‘stuffed their mouths with gold’. There were disagreements in the government about which services should require fees, with some private wards being maintained allowing patients access to private healthcare in NHS hospitals. Bevan eventually resigned in 1951 at proposed new charges for dental and eye care.

Since that time, the NHS’ remit to provide healthcare free at the point of use has been largely maintained, although limited prescription charges have been in place since the 1960s. The Mental Health Act of 1959 made provisions for people with mental health problems while the UK’s first heart transplant took place in 1968. A register of NHS organ donors was created in 1994 and NHS Direct was launched in 1998, allowing patients to receive clinical advice over the phone. Other reforms since the 1980s have largely focused on the extent of the ‘internal market’, which sees health authorities purchase services from other providers, and on the outsourcing of services to private firms.

In over seventy years the NHS has overseen the vaccination of millions of people, from the introduction of the polio vaccine in the 1950s to the fight against the coronavirus pandemic in 2021. It has seen infant mortality rates collapse and life expectancy soar. It remains arguably the most beloved institution in the UK.

The History of the NHS | Nuffield Trust

By Simon Hilditch

June suns, you cannot store them To warm the winter’s cold, The lad that hopes for heaven Shall fill his […]

Harford Montgomery Hyde was a Belfast-born barrister, politician, author, and humanist, who championed humane legal reforms and progressive social attitudes. […]

It is necessary to the happiness of man that he be mentally faithful to himself. Infidelity does not consist in […]

Good writing excites me, and makes life worth living. Harold Pinter Harold Pinter was one of the 20th century’s most […]