We are living in critical days. It is not enough to desire peace or to talk peace. We must make personal decisions and live peace.

Aldous Huxley, An Encyclopaedia of Pacifism (1937)

The Peace Pledge Union is the oldest secular pacifist organisation in Britain, and has campaigned for peacebuilding, nonviolence, and remembrance since 1934. It is perhaps best known today for organising the white poppy campaign, which promotes remembrance for all victims of war and an alternative to any glamourisations or celebrations of conflict. Although initiated by an Anglican priest, humanists (including Bertrand Russell and Laurence Housman) were prominent among the Union’s earliest supporters, and have long been an active presence in the PPU, and in many other efforts toward the creation and maintenance of peace.

War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determined not to support any kind of war. I am also determined to work for the removal of all causes of war.

The Peace Pledge

The PPU was born of a campaign initiated in 1934 by Christian pacifist Dick Sheppard, who in an open letter encouraged men to send him postcards pledging never to support another war. Fifteen years after the end of the First World War, he felt the nations of Europe were risking another catastrophic conflict. He wrote of ‘the almost universally acknowledged lunacy of the manner in which nations are pursuing peace’ and encouraged others to renounce war, and to pledge never to support or sanction another one. The response was overwhelming, with tens of thousands of replies received within a few weeks. In July 1935, Sheppard addressed a demonstration of 7,000 at the Albert Hall, inaugurating the ‘Sheppard Peace Movement’. In 1936, this became the Peace Pledge Union: open to ‘men and women of… divergent philosophic, religious and political opinions’. Peace News was launched as an associated weekly newspaper.

Sponsors of the Peace Pledge Union included a number of prominent humanists and freethinkers, notably Bertrand Russell, Aldous Huxley, Storm Jameson, and Laurence Housman. George Lansbury, a Labour politician whose children had attended the secular Sunday School of the East London Ethical Society, was also a member, as was composer Benjamin Britten. Britten wrote of his pacifism that:

The whole of my life has been devoted to a life of creation (being by profession a composer) and I cannot take part in acts of destruction.

Benjamin Britten, quoted in ‘Britten, (Edward) Benjamin, Baron Britten‘ by Donald Mitchell, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

A number of other well-known humanists, though not members, wrote and spoke in support of the PPU. These included philosopher C.E.M. Joad, and authors Ethel Mannin and Virginia Woolf.

The idea of alternatives to wearing a red poppy, in order to commemorate all victims of war, had been introduced by the No More War Movement in 1926, and white poppies were made and sold from 1933 by the Women’s Co-operative Guild. Initially, people wearing white poppies were met with considerable hostility, with many veterans believing it to undermine the significance of the red poppy, worn since 1921 to support members of the British Armed Forces. Many of the women involved in the movement lost their jobs as a result. Supporters of the white poppy felt that it better symbolised the initial Remembrance Day message of ‘never again’. In 1936 the production of white poppies was taken over by the PPU, which coordinates the campaign to this day. In 1937 the No More War Movement, which had campaigned for peace and against conscription since its foundation by humanist Fenner Brockway in 1921, officially merged with the PPU.

In the years leading up to the Second World War, the PPU supported Neville Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany. Alfred Salter, a socialist, agnostic, and key figure in the PPU, was quoted as saying:

I denounce Hitler’s brutal methods as much as anyone, but there is no cause on earth that is worth the sacrifice of the blood and lives of millions upon millions of innocent and helpless men, women and children… Our present attitude helps to rally [the German people] behind him today.

PPU members campaigned against legislation for military conscription and supported the conscientious objectors who refused to join the armed forces. Hitler’s invasion of France in 1940 caused a number of high-profile members to leave the PPU. Novelist and atheist Margaret Storm Jameson wrote that she had joined because: ‘I was absolutely certain that war is viler than anything else imaginable… I don’t think that now.’

The PPU adopted a position of supporting refugees from Europe, as they had done previously during the Spanish Civil War. But during the war the PPU and wider pacifist movement were subject to severe criticism and membership began to fall. George Orwell summed up the critical public mood in 1941:

Since pacifists have more freedom of action in countries where traces of democracy survive, pacifism can act more effectively against democracy than for it. Objectively, the pacifist is pro-Nazi.

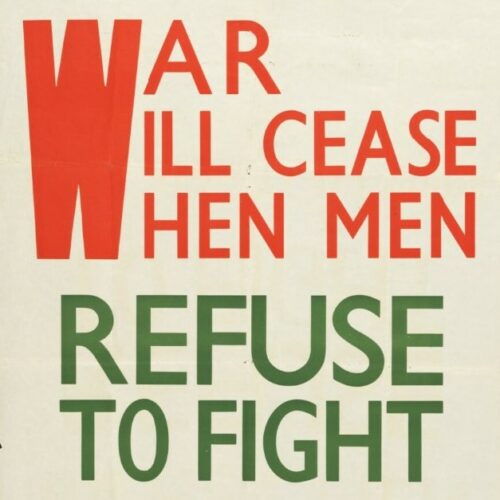

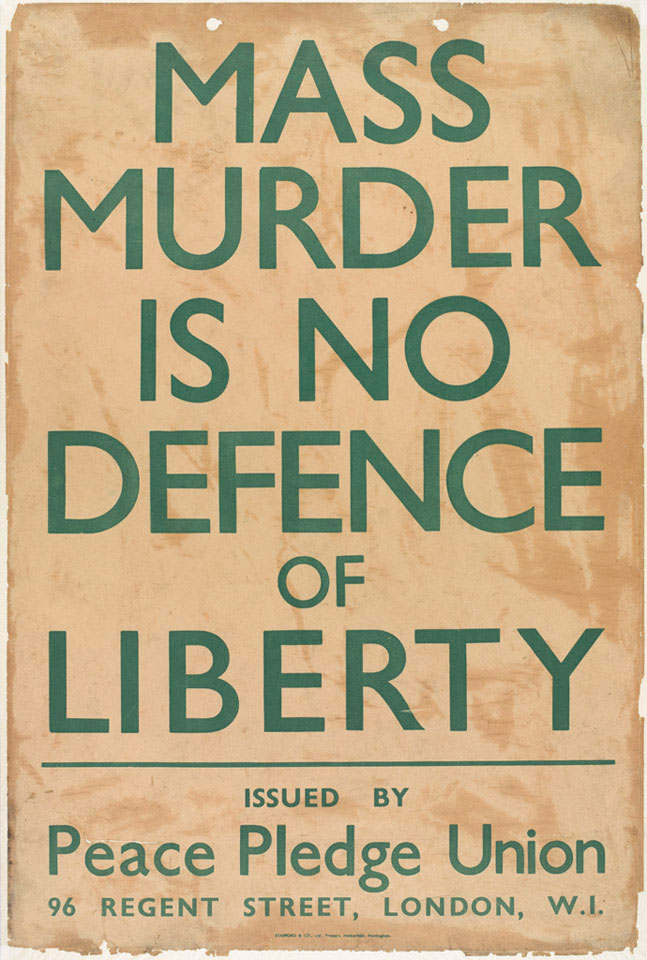

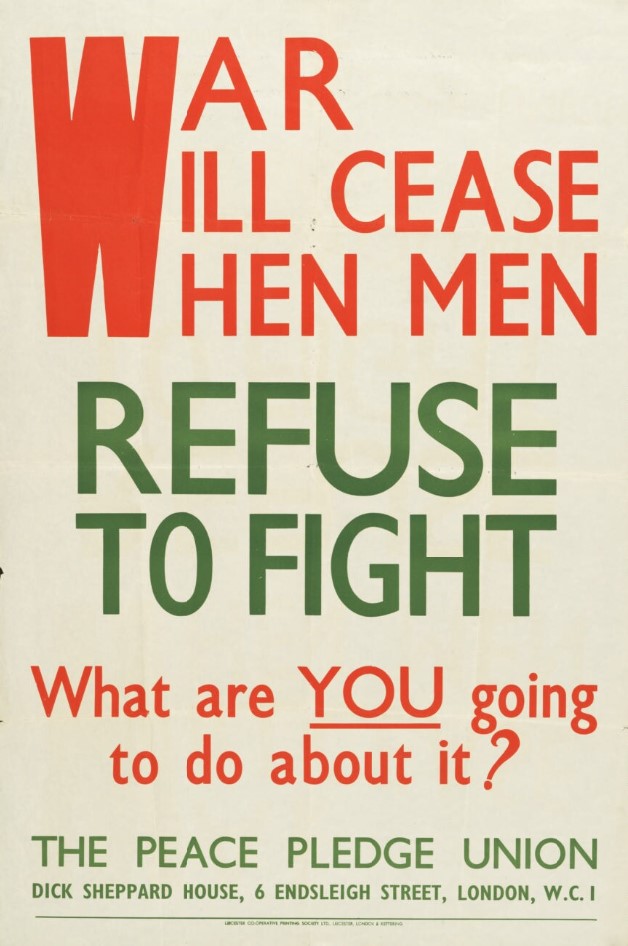

Members of the PPU were arrested for sowing disaffection among the armed forces and civilian population alike, including with the production of a poster stating that ‘War will cease when men refuse to fight. What are you going to do about it?’ As the war developed, the PPU began to focus less on calling for peace negotiation and instead supported food relief campaigns and the rights of conscientious objectors.

In the decades following the Second World War, the PPU has been well-represented in numerous campaigns and movements, including for nuclear disarmament, non-violent civil disobedience in India, and against the war in Vietnam. They have also taken active positions against the British Army’s involvement in Northern Ireland and the invasion of Iraq. Recent years have seen a resurgence in the popularity of the white poppy campaign, with record sales now reaching over 100,000 each year.

White poppies tell the story of the alternative Remembrance Day | Co-operative News

By Simon Hilditch

Is being rewarded for maintaining certain articles as matters of faith, and being punished, or suffering for opposing them, proper […]

I had long put on one side the purist pacifist view that one should have nothing to do with a […]

It is not because the believer in rational religion has not clear convictions that he will not shape them into […]

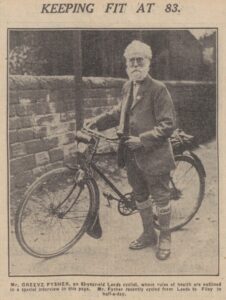

Mr. Fysher was in many respects a remarkable man. His interests were wide, and whatever he took up he carried […]