Without this mutual trust and dependability amongst people who differ radically, there cannot be political and religious freedom.

H.J. Blackham in the Ethical Record (1967)

The Social Morality Council was formed in 1966 to bring the religious and non-religious together in the discussion of moral issues. Its predecessor was the Public Morality Council, which had been concerned primarily with obscenity and pornography. The Social Morality Council was to have a much broader focus, with an emphasis on the common ground occupied by religious believers and humanists in the realms of morality and public policy. It later became the Norham Foundation, maintaining a strong focus on effective, inclusive moral education in schools.

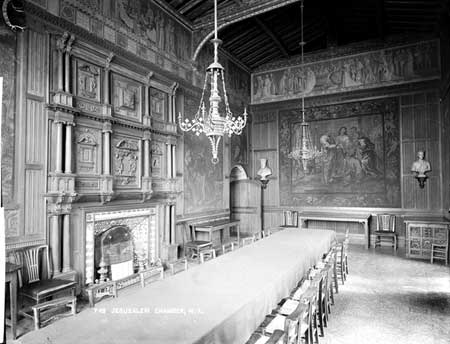

The first meeting of the Social Morality Council took place in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey in December 1966. Its President was Bishop Joost de Blank, the former Archbishop of Cape Town, who saw the responsibility of the Council as ‘restoring the springs of the democratic processes that have got rusty over the years.’ It aimed to foster non-sectarian solutions to social problems, bringing together representatives of all faiths and none. Hector Hawton, writing of this inaugural meeting in The Humanist, described: ‘Humanists on each side of me, Salvationists in front, a well known Communist behind, and clergy everywhere.’

As Harold Blackham explained, the Social Morality Council arose from a recognition that Christian morality could no longer serve as the sole basis for wide reaching moral discussion and legislation:

Turning from theory to practice, the question is what kind of a consensus our society needs today, now that the traditional religious consensus has lost effective influence. Some basic agreements are needed for legislation, for public opinion, for education. They cannot any longer be agreements in ultimate belief and conviction; they can only be agreements of a political and moral character. The need for such agreement is constantly being voiced in the press. One striking indication of the new situation is the case of the sixty-year-old Public Morality Council sponsored by the churches and preoccupied with sex morals. A decision has been taken to reconstitute it as a Social Morality Council, to broaden its scope to take in a concern for the urgent problems of mankind (hunger, war, population), and to invite the co-operation of humanists, marxists, and others outside the churches. This move amounts to a recognition on the part of the authorities that society demands a more broadly based consensus than religion can supply.

The Social Morality Council addressed itself to international peace and poverty, religious and moral education, compulsory collective worship, broadcasting, sex education, and a range of other topics, producing reports and organising conferences.

In March 1967, the Social Morality Council and the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) held a meeting at Conway Hall on abortion law reform, with the specific aim of ensuring that women’s voices were heard. Representatives from the Abortion Law Reform Association and the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children spoke, and the National Council of Women also sent committee members. The proceedings were bookended by Dr. Marita Harper and Isobella Graham, representing the Social Morality Council and the BHA respectively. Writing of the impulses behind the meeting in the Ethical Record, Barbara Smoker said:

It may seem pointless to attempt to bring together the strongest opponents and supporters of this Bill, in the hope of finding any common ground between them, but we all have to live together in the same world and we are all faced with the same practical problems. Anyway, the confrontation can do no harm, and it is just possible that some good may come out of it.

In 1970, the Social Morality Council published a report on Moral and Religious Education in County Schools, and in 1971 founded The Journal of Moral Education, which remains in publication today. The Council also founded the Moral Education Project, which aimed to offer ‘comprehensive support and information… for teachers and parents’ and ‘to promote a closer partnership in moral education between home and school, so that they do not, as too often happens, work at cross-purposes.’ In December 1971, they held a day-long conference called ‘Humanly Speaking’, aiming to reinforce the work of the Social Morality Council by encouraging the formation of local and regional groups.

In 1974, the Social Morality Council published The Future of Broadcasting, the result of a study conducted by a commission of 19, led by Dame Margaret Miles, a London headteacher. In the same year, speaking in the House of Lords, Fenner Brockway expressed his admiration for the work of the Council:

I regard the efforts of the Social Morality Council, representing Christians of all the Churches and those of us who are Humanists as well… as so important. I hope that they will enable us to go through this transitional period of disbelief into a more glorious belief, which will be an inspiration for the generations to follow to build the better human society which we are seeking.

Fenner Brockway, ‘Moral Education In State Schools’, Tuesday 10 December 1974, Hansard – UK Parliament

In the early 1990s, the Social Morality Council became the Norham Foundation. Chairmen included H.J. Blackham and Hermann Bondi, and moral education and responsible citizenship remained central. Reporting on a conference on citizenship education, held at Churchill College, Cambridge in 1999, the New Humanist wrote:

Humanists should surely support citizenship education – not because we want to create neat, tidy, impeccably behaved clones all constantly kow-towing to each others’ rights and values, but because we want to live in a society where everyone has a place, where varieties of lifestyle can be enjoyed and where participation in society gives everyone a chance of fulfillment.

Living in a house beautifully situated on the outskirts of Coventry, they used to spend their lives in philosophical speculations, […]

No one can be perfectly free till all are free; no one can be perfectly moral till all are moral; […]

It is a principle innate and co-natural to every man to have an insatiable inclination to the truth and to […]

… purely human and natural ethics, and not theology, was the source of this pioneer woman’s enthusiasm for justice, even […]