The old teaching was that we must worship not truth, beauty and goodness, but their source, and that their source is personal intelligence of infinite power. The new idea is that not their source, but these glories themselves, these absolute values, regardless of the source whence they flow, are worthy of absolute reverence and utter obedience, and are on that account to be worshipped and adored as God.

Stanton Coit, ‘What do you mean by ‘God’?’

The Ethical Church was both a building in Bayswater and, from 1914, the name of the West London Ethical Society, led by Stanton Coit. It was the most prominent experiment by any among the ethical societies in ‘social worship’, but featured a deliberate attempt to separate the words ‘god’ and ‘religion’ from their traditional theological meanings; substituting the virtues of truth, beauty, and goodness for a divine being, and the pursuit and practice of these virtues for theological religious worship. Like the other ethical societies, the Ethical Church prized practical morality, social reform, and a sense of community above all else, but might be compared to the positivist ‘Church of Humanity’ in the more ritualistic aspects of its Sunday ‘service’.

The old creeds said, with Browning: God! Thou art love! I build my faith on Thee. The new creed says: Love! Thou art God! I build my faith on Thee!

The building at 46 Queen’s Road, Bayswater, was secured in 1909, with significant financial support from Adela Coit, to act as the headquarters of the West London Ethical Society (formed in 1892). In that year, the Society had its highest ever number of subscribers (470).

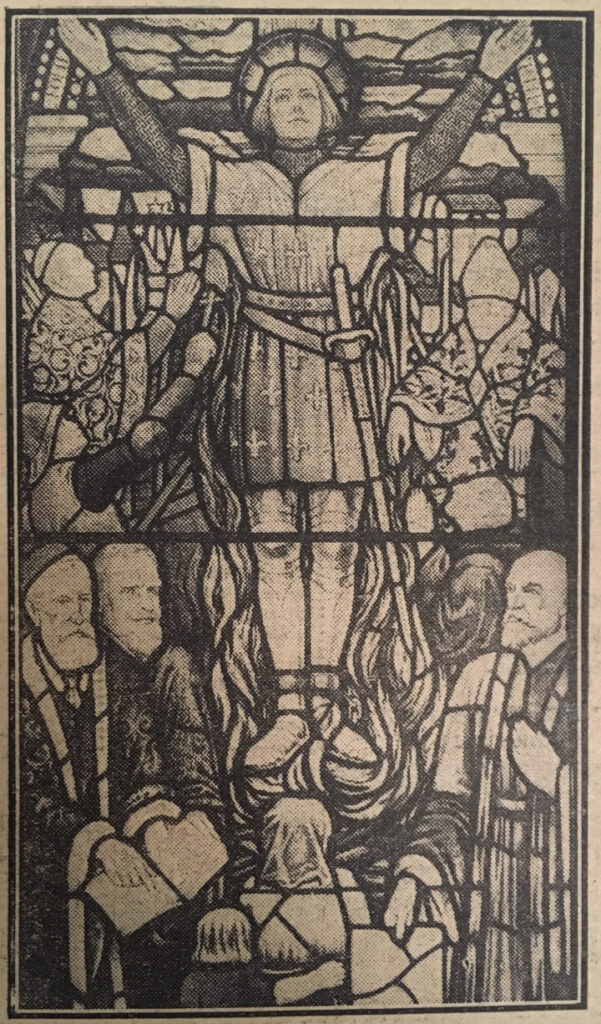

The group quickly set about decorating the building to reflect their values and honour their heroes: figures from the realms of art, literature, philosophy, and social reform. Throughout the Ethical Church were portraits, busts, and quotations from figures including George Frederick Watts, Matthew Arnold, Giuseppe Mazzini, Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Felix Adler, Leslie Stephen, Henry Sidgwick, Josephine Butler, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. The Church’s colour scheme and pulpit were the design of Walter Crane, a painting by whom hung centrally. In time, three stained glass windows would depict Joan of Arc, Elizabeth Fry, and Florence Nightingale.

At a meeting on 16 October 1914, the West London Ethical Society officially became the Ethical Church. The principles of the group remained centred on the pursuit of the ‘good life’, and its independence of any external authority or belief in supernatural punishment or reward. It also included a redefinition of traditional concepts such as ‘religion’ and ‘God’; Coit referred to this as ‘Theological Terms in a Humanistic Sense’. For the members of the Ethical Church, religion implied any focused attention on the perceived source of life’s ‘blessings’. As such, the ethical religion focused instead on the ‘Moral Ideal’. Three ‘sources of insight and strength’ replaced the concept of a god: ‘the Ideal of truth, beauty, and goodness’, ‘Individual Human Beings in so far as their life and thought embody the ideal’, and the ‘Group-Spirit… of persons who are trying to make the world more nearly perfect’.

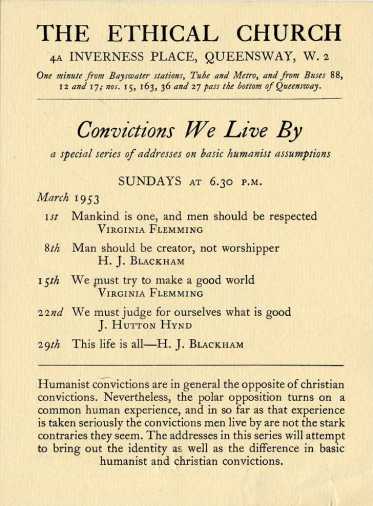

The Ethical Church held two Sunday services weekly, and made use of Social Worship, an ethical anthology edited by Coit (Volume I) and Charles Kennedy Scott (Volume II). There were also special services, including for the ‘dedication’ of children, marriage, and funerals: precursors of today’s humanist ceremonies. The group also honoured ‘Woman’s Sunday’, and held an All-Nations’ service on Armistice Day.

The Ethical Church was closely connected with suffrage efforts, with Adela and Stanton Coit both active participants in the fight to gain voting rights for women. In 1913, they welcomed American suffragists Anna Shaw and Charlotte Perkins Gilman to the Ethical Church, both of whom delivered addresses. That year Adela Coit and other members of the society established the Spiritual Militancy League, as representative for which Margaret Wetzlar Coit attended the congress of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Budapest, alongside Adela who sat on its executive board.

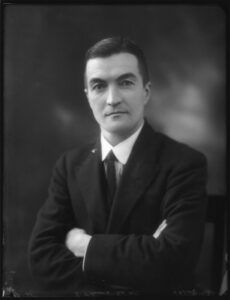

During the 1930s the Ethical Church faced a dwindling ‘congregation’ and competition from the lively South Place Ethical Society, with its newly opened Conway Hall. During this time, H.J. Blackham became joint leader of the Ethical Church, with Harry Snell and Stanton Coit‘s daughter Virginia. From 1933, Blackham was ‘minister’.

Stanton Coit died in 1944, and in 1953 the Ethical Church was sold, the profits being used to purchase 13 Prince of Wales Terrace. The name of the Society reverted to the West London Ethical Society, which continued until it was dissolved in 1965. The property at Prince of Wales Terrace later was the headquarters of the British Humanist Association until its move to Lamb’s Conduit Passage in 1990.

Virtue alone is enough to live happily and brings its own reward. John Toland, Pantheisticon (1720) John Toland was an […]

Socialism emerged, in the early decades of the nineteenth century, as a humanist ideal of universal emancipation – the ideal […]

There is no hope but us. There is no mercy but us. There is no justice. There is just us… […]

It was early in the war, and we were stationed at a pleasant village in Sussex. One evening a sergeant […]