Thomas Hardy was an English novelist and poet, renowned for his apparently bleak outlook, but finely tuned to life and language. Virginia Woolf, who knew Hardy, described him as a ‘powerful imagination, a profound and poetic genius, a gentle and humane soul.’ Hardy’s curiosity and rationalism inclined him early toward the questioning of religious doctrine, drawing him to the science and philosophies of Darwin, Spencer, and other agnostic thinkers. Hardy’s own expressed agnosticism, married to a sensitive, imaginative humanity, secure his place in the humanist tradition.

Thomas Hardy was born in Dorset on 2 June 1840, the son of a stonemason. His family, though Anglican, were not devout. The musicality of his fiddle-playing father, and literary tastes of his mother, Jemima Hand Hardy, were influential. Hardy’s formal education concluded at 16, and he became an architectural apprentice, later training at King’s College, London.

Hardy lost his faith in Christian dogma early in life and became an agnostic. He described himself as ‘among the earliest acclaimers of The Origin of Species’ and, indeed, turned to the work of figures like Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer for an alternative view of the world and man’s place in it. He was also drawn to the writings of Auguste Comte, John Stuart Mill, Matthew Arnold, and Leslie Stephen, all of whom occupy significant positions in the history of humanist thought. Replying to a letter from Scottish clergyman and literary editor A.B. Grosart about the reconciling of evil with the goodness of God, Hardy wrote:

Mr. Hardy regrets that he is unable to offer any hypothesis which would reconcile the existence of such evils as Dr. Grosart describes with the idea of omnipotent goodness. Perhaps Dr. Grosart might be helped to a provisional view of the universe by the recently published Life of Darwin and the works of Herbert Spencer and other agnostics.

Hardy’s novels often engaged with religious themes and he featured many negative portrayals of members of the clergy in them, as well as exploring what he saw as the potentially damaging effects of Christian moral teachings. In many of his novels he referred to Christianity as being outdated and redundant, with no relevance to the everyday lives of the masses, although he also used Biblical imagery and Christian concepts of charity approvingly in some of his work.

Engaging with the work of Matthew Arnold and the late Victorian debate about modernism and the Church, Hardy rejected the idea that Christianity could be adapted to modern thought, and neither could it be blended with a return to a more ‘natural’, pagan religion. Ultimately, the retention of Christian morals and sexual codes by his ‘modernist’ characters, including Clym in Return of the Native (1878), Angel in Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) and Jude in Jude the Obscure (1895), sees their tragic downfalls, and Hardy was principally concerned with the effects of Christian morality on individuals trying to adapt to an otherwise changing world.

Thomas Hardy died in 1928, leaving behind a rich body of work which included, in the words of Claire Tomalin, some of the ‘finest and strangest celebrations of the dead in English poetry’. His ashes were interred in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, and his heart in the Stinsford graveyard where his parents and first wife were buried.

In his complex exploration of the decline of the Christian religion, Hardy made a significant contribution to the debate about the changing nature of religious faith in late 19th and early 20th century Britain. His poems, sensitive expressions of his own attitudes and hardships, were formative in the work of many modern poets, and continue to be read and studied widely.

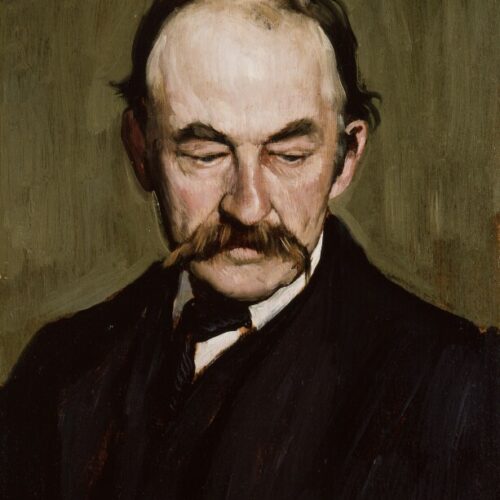

Main image: Thomas Hardy by William Strang, 1893 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Girton College at the University of Cambridge has educated and employed a host of remarkable humanists and freethinkers, many of […]

For I am not everlasting, but a human being, a part of the whole as an hour is a part […]

‘Being Rational About Being Gay’ was a talk given by activist Antony Grey (Anthony Edgar Gartside Wright) for the Gay […]

We are (of all the synonyms I most prefer to ‘humanist’) freethinkers. We are deprived of nothing. We have lost […]