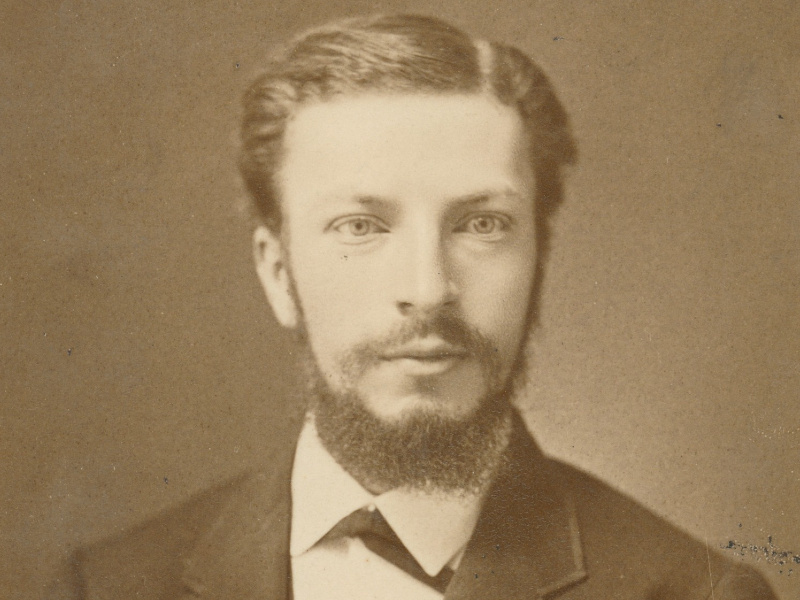

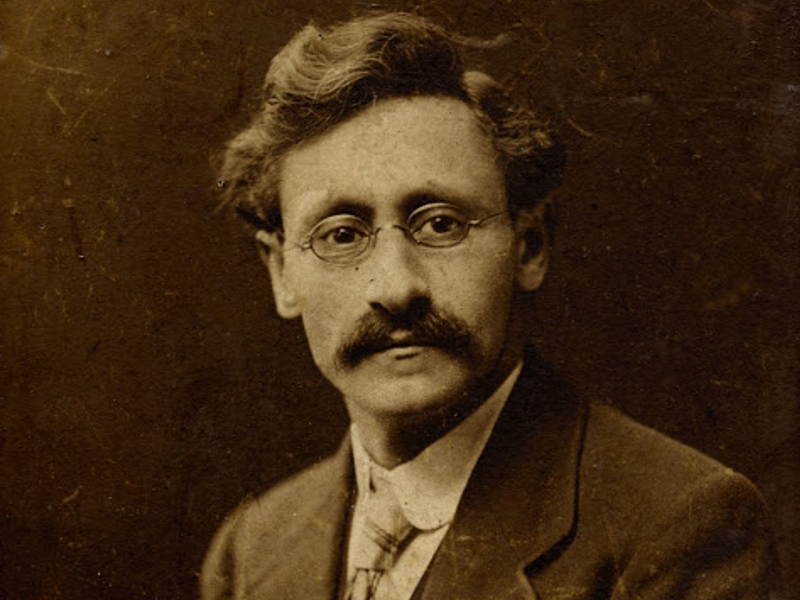

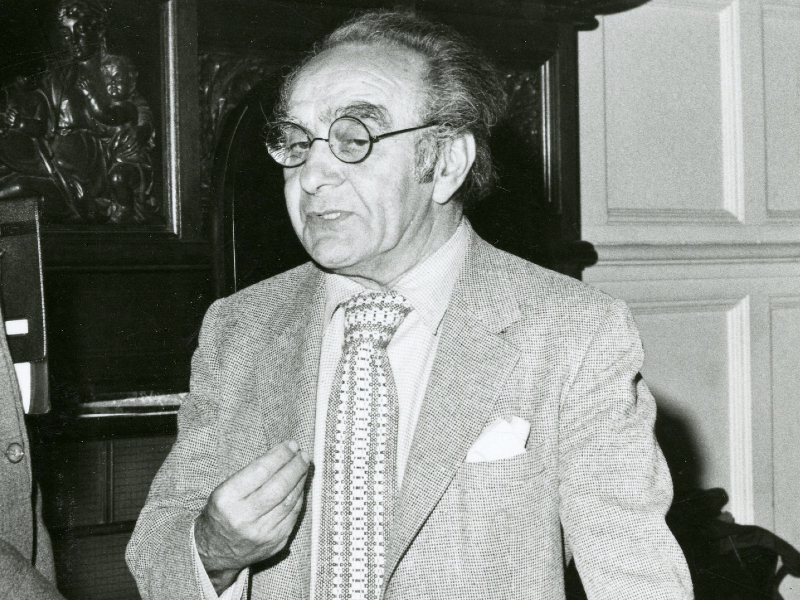

Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677)

Born in Amsterdam in 1632, Spinoza has been called the ‘founding father of modern unbelief’. He rejected the concept of miracles, and denied the efficacy of prayer, asserting that God was the substance of nature. For some, Spinoza’s name became synonymous with atheism, for others with pantheism, but though he never argued against the existence of a deity, he nevertheless placed the responsibility for living squarely with humankind. In dispensing with supernaturalism, and emphasising instead human beings’ capacity to strive for goodness – with no expectation of divine intervention, punishment, or reward – Spinoza laid the groundwork for the vocabulary of humanism today.