People have always looked for ways to mark significant events in their lives, and though many ceremonies have often been associated with religious ideas (such as baptism, or a church marriage), non-religious people have long sought out ceremonies more representative of their own values. In so doing, they have created personal and meaningful events to mark the most important moments in their lives. Today, Humanist Ceremonies take place across the world, and Humanists UK has been supporting non-religious people to organise them across its entire history.

Humanists UK has its direct origins in the ethical societies of the 1880s: groups formed for the purpose of living well without reference to supernatural ideas. From these earliest years, members and leaders of those societies were creating ceremonies in line with their values. These included marriage ceremonies (in which the duties of each party to one another, and to the wider community, were emphasised), and funerals (which, dispensing with ideas of life after death, centred on the life and legacy of the deceased). These ceremonies, building on an existing tradition of non-religious ritual, were the direct ancestors of today’s Humanist Ceremonies.

The Owenites: early humanist naming ceremonies

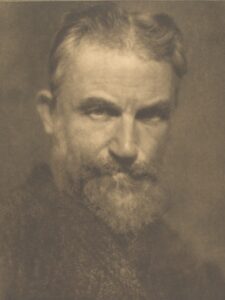

Certain ceremonies are common to all human society, and should be consistent with the opinions of those in whose name the ceremonies take place.

George Jacob Holyoake, English Secularism: a Confession of Belief (1896)

Non-religious naming ceremonies are on record as taking place as early as 1849, when the Owenite freethinker George Jacob Holyoake wrote about the secular naming ceremony he carried out for his close friend, the radical publisher Edward Truelove. Holyoake’s own definition of ‘secularism’ (a term he coined in 1851), was synonymous with our definition of ‘humanism’ today – emphasising our responsibility for one another, and ourselves, in this life.

In common with humanist ceremonies today, this naming was seen as an alternative to a church-led ceremony, and put emphasis on the act of naming a child, as well as the child’s autonomy to decide for themselves about religion as they grew older. Truelove’s son was given the name ‘Mazzini’, honouring Italian revolutionary Guiseppe Mazzini, and Holyoake asked the community to assist in bringing the child up with values of kindness, self-reliance, independent thought, and bravery. The best way to do this, he suggested, was to embody those values themselves.

It is not in conformity with my ideas of usefulness to invoke, as the Church would do at the conclusion of this ceremony, your benediction upon this child. But let me remind you that there is a greater benediction than prayer in your power to pronounce. If you gather up the words spoken tonight, and realise them in your practice – if you can work with heroic devotion for the improvement of others in the spirit of that system which has just been explained… you will smooth the way of this young child through the world.

Holyoake, and those gathered for Mazzini Truelove’s naming, were followers of philanthropist and reformer Robert Owen (1771-1858), whose ideal of a ‘rational religion’ – rooted in reason, compassion, and a sense of responsibility for others – was essentially humanist. The Owenites sought radical social change, advocating communal living, cooperative working, and a ‘rational religion’, based not on any god but on the role of human beings in bringing about a better world. These ideas influenced a swathe of later freethinking reformers, including Margaret Chappellsmith, George Jacob Holyoake, and Frances Wright. Holyoake himself, as well as his daughter, Emilie, were active supporters of the Ethical movement – which by the middle of the 20th century had become more widely known as the ‘humanist’ movement.

An ‘ethical marriage’

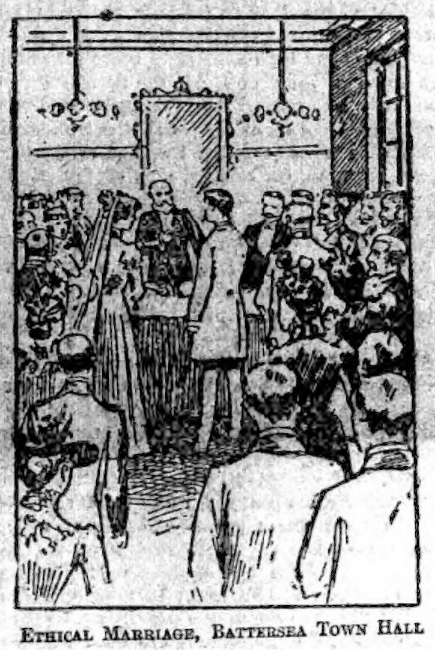

In December 1898, newspapers reported the marriage of Stanton Coit and Adela Wetzlar, two of the Ethical movement’s most prominent figures. Coit was, like Moncure Conway, an American who helped to shape the organised humanist movement in the UK. Adela Wetzlar was an internationally significant suffragist, who went on to play an active part in the Ethical movement alongside her husband. The ‘ethical ceremony’, which took place in Kensington Town Hall, was conducted by Frederic Harrison. Harrison was both an ethical society member and a leading figure in the humanist positivist movement – a ‘religion of humanity’ drawing on the ideas of French thinker Auguste Comte – leading to references in the press to an ‘Ethical Positivist marriage’. This ceremony, newspapers noted, took place immediately after the civil one, adding that the ‘keynote’ of Harrison’s speech was ‘the social happiness to be derived from the condition of domestic bliss’.

The following year, in Battersea Town Hall, West London Ethical Society members William Sanders and Beatrice Martin were married in what newspapers again referred to as an ‘ethical wedding’. Beatrice Sanders (1874–1932), would later become financial secretary to the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Her husband was Labour MP William Sanders (1871–1941). Their wedding, conducted in 1899 by Stanton Coit, was another early example of a humanist marriage ceremony, and emphasised the ‘Ethical idea concerning the marriage state, the duties of the parties one to the other, and their combined duty to the community of which they formed a part’.

Not only did members of the early humanist movement conduct their own ceremonies, they openly challenged what they deemed to be inequalities in traditional religious services. A manifesto issued by members of the West London Ethical Society in 1913, for example, referred to the ‘moral indignities’ of a woman being ‘given away’, or asked to serve and obey her husband.

Funerals without ‘theologies’

In line with the humanist belief that this life is the only one we have, humanists throughout history have naturally sought to create funeral ceremonies aligned with their own understanding of death – and the meaning of life. Just like namings and marriages, humanists have been carrying out meaningful funeral services for well over 100 years. A number of prominent freethinkers during the 19th and early 20th centuries also published collections of possible readings, and suggestions for services. Typically, these ceremonies focused on the life and character of the person who had died, reminding those who loved them that it was through their memories of the person that they might have life beyond death – not any afterlife or reincarnation.

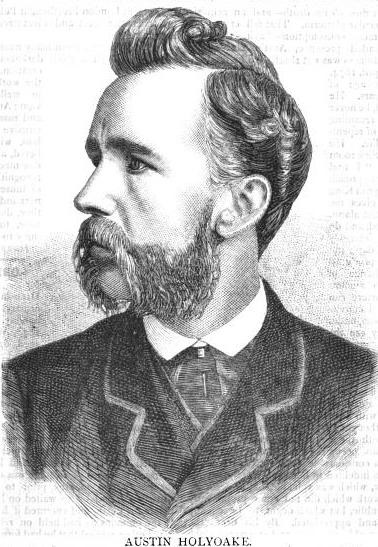

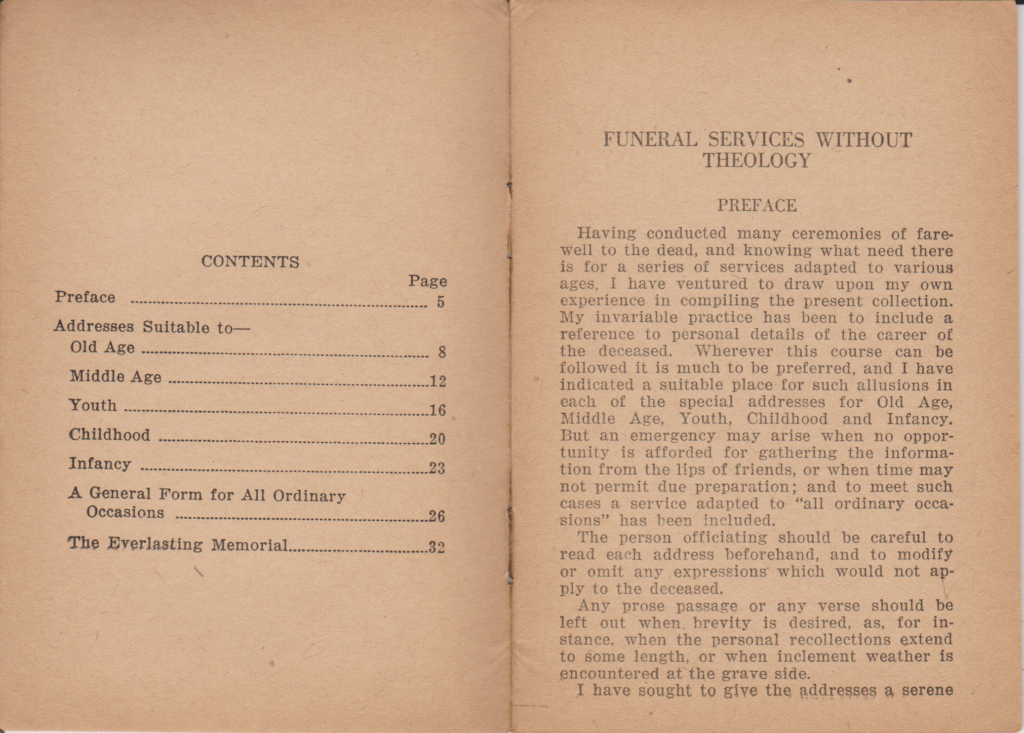

The Secularist’s Manual of Songs and Ceremonies, which included naming, marriage, and funeral services by Charles Watts and Austin Holyoake, was published in 1871. In 1906, humanist educationist Frederick James Gould first published Funeral Services without Theology, with suggestions for suitable services according to old age, middle age, youth, childhood, and infancy. This was designed in part, noted the Literary Guide (now the New Humanist) to meet a growing need for non-religious ‘officiators’ at funerals.

Moncure Conway was the pioneering humanist who gave his name to London’s Conway Hall, having guided what was previously a Unitarian congregation towards a humanist, secular approach to morality and ethics. Among the ceremonies conducted by Conway were the non-religious funerals of Pre-Raphaelite artist Ford Madox Brown and his son, and the weddings of Brown’s daughters.

Conway was a close friend of Brown’s, recalling in his autobiography:

With Ford Madox Brown I was on terms of particular intimacy because of his sympathy with my religious heresies. I assisted at the marriage of his daughters (one to Franz Hueffer, the musical critic, another to William Rossetti), and I conducted the funerals of his son and himself.

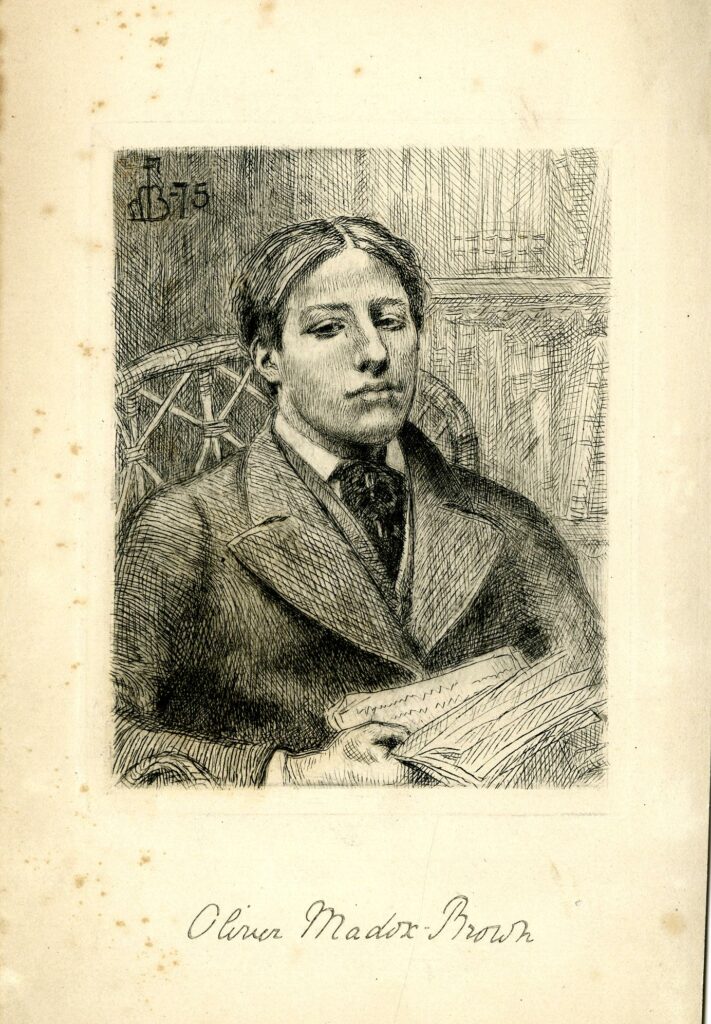

In his description of the funeral of Oliver Madox Brown, who died in 1874 at just 19, the shared humanism of Conway and the bereaved father, are evident:

Ford Madox Brown, in his letter requesting my services at the funeral, expressed to me his disbelief of all theologies. But although without any of these hopes of future life in which believers find consolation, I never knew in all my ministry, whether among Methodists or Unitarians, more courage than was displayed by this devoted father under unexpected and terrible affliction. Stricken as by a thunderbolt, he was yet not shattered. He set himself to soothe the bereaved ones around him; he sustained them on his great heart; and he never faltered in devotion to his art.

When Brown himself died, in 1893, Conway conducted a funeral for him in line with these humanist beliefs.

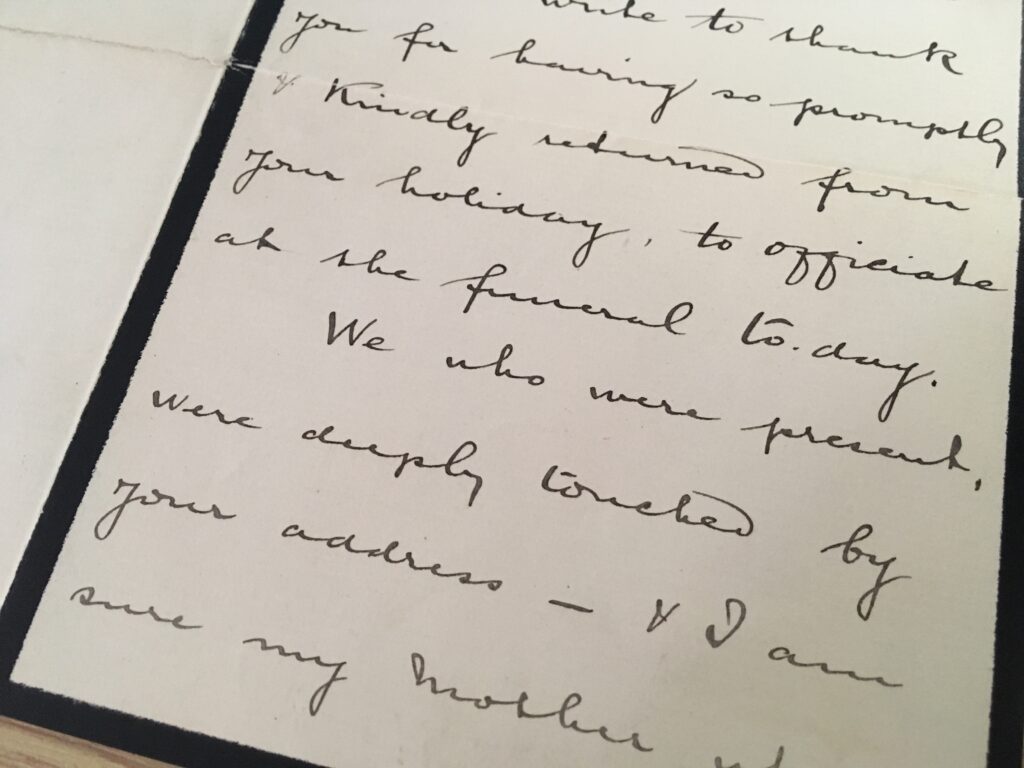

From the earliest days of the Ethical movement, leaders and members of the ethical societies carried out funeral services in line with their non-supernatural beliefs. One letter, written to Stanton Coit in 1889, thanked him for the ‘tender feeling and beautiful sentiment’ expressed by Coit in a funeral for George Hickson, the letter-writer’s father.

George Hickson (1819-1889), was a shoe manufacturer and treasurer of South Place (now Conway Hall Ethical Society). Coit led his funeral on 30 July 1889. Hickson, and his wife, had attended South Place from their childhood, and were married there in 1842 by William Johnson Fox. Conrad Thies, writing in the Ethical Record in 1902, emphasised the importance of funerals – like Hickson’s – which were truly representative of the values of the deceased. Such services were not only more meaningful for those involved, but testified to the meaning and morality of the humanist outlook – still a matter of considerable debate in the early 20th century. Thies wrote:

Such men as… our former treasurer Mr. George Hickson, and many other members of our Society who have passed away, leaving records of good and blameless lives, refute the wide-spread fallacy that mankind can only be kept moral by a system of rewards and punishments hereafter. We are right to cherish their memories, and to take encouragement from their example, so that when our time of departure comes we shall each be found ready to face the inevitable end with a calm mind and unflinching courage.

Thirty years later, Adela Coit (whose ‘ethical marriage’ had taken place in 1898) had a humanist service on her death in 1932. Led by organist and choral conductor Charles Kennedy Scott, it featured poetry (set to music) from Shakespeare and Walt Whitman, and prominent humanist Harry Snell said:

Let us… not grieve for what we shall no longer see: let us be glad for the life that was; for its service and example… And now let us do what she would most have wished – return to our own work in the world, that those who still live in it may have life more abundantly.

Towards today’s Humanist Ceremonies

Years later, in Humanism (1968), H.J. Blackham would write:

If in a broad sense ‘religion’ is taken to mean an inner world of personal belief and response and ‘politics’ an outer world of regulated conditions of modern life, ‘ritual’ is an intersection where a personal event takes place in a social context. Birth, marriage, and death are private events of moment which have this public face. They call for publicity, solemnity, celebration, public participation… Humanists would like to see whatever social rituals are needed dissolved from particular religious rites, so that they may be universally shared.

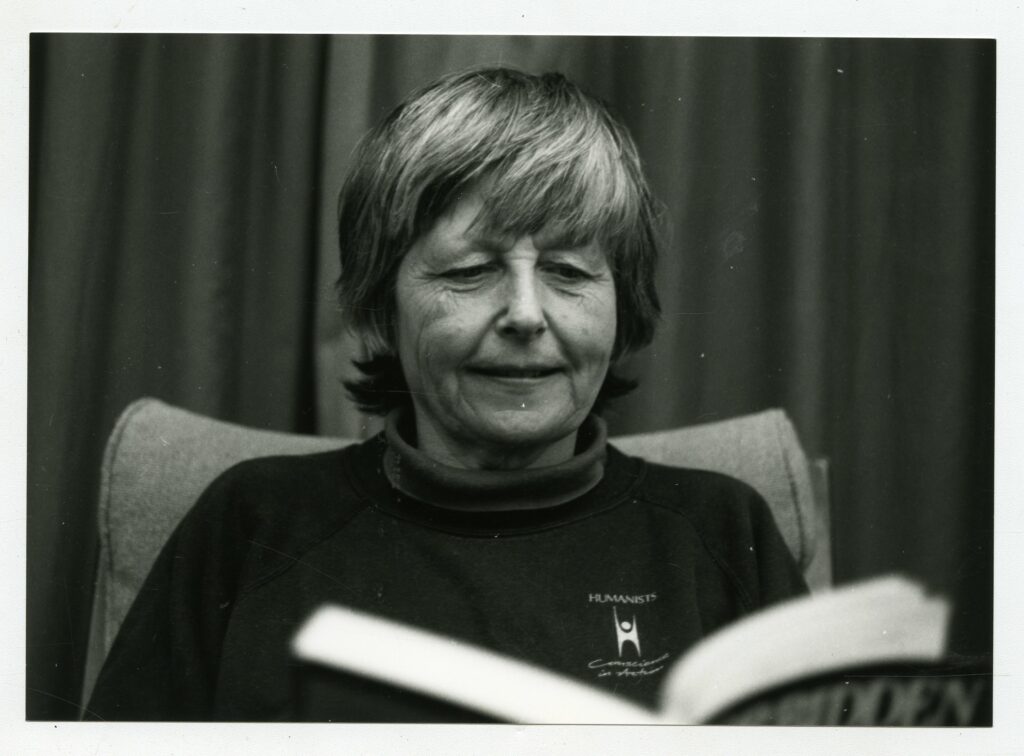

In 1983, Nicolas Walter gathered a collection of suggested readings for humanist funerals and published them in the New Humanist. In the same decade, the British Humanist Association (now Humanists UK) published Jane Wynne Willson’s To Love and to Cherish (1988, later Sharing the Future), and Funerals Without God (1989), followed in 1991 by New Arrivals. Throughout these decades, growing demand for humanist celebrants saw the increasing professionalisation of the network, including dedicated training, guidance, and accreditation for celebrants. By the 21st century, the strong reputation of humanist ceremonies had reshaped demand for marriages, funerals, and namings – including in religious organisations – inspired by the humanist emphasis on personalisation, values, and the uniqueness of every occasion.

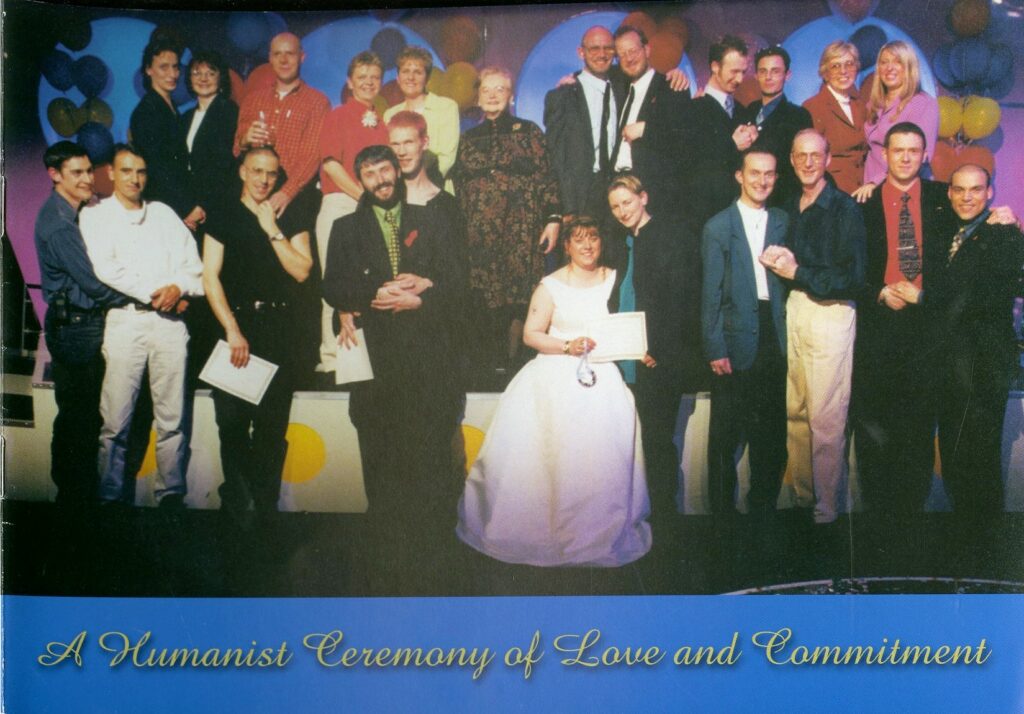

Humanist ceremonies also reflect the humanist commitment to equality. From its formation in 1979, the Gay Humanist Group (now LGBT Humanists), offered same sex commitment ceremonies – decades before civil partnerships or same sex marriage would become legal. Naming ceremonies have also become popular for trans people announcing their new identity to the world.

The story is ongoing. In recent decades, there has been growing legal recognition of the equal right of humanists to marry in a legally binding humanist ceremony. In Scotland, where members of Humanists UK first set up the charity Humanist Society Scotland in the mid-1980s, humanist celebrants were finally given legal recognition in 2005. Following a legal case, this followed for Humanists UK and its section Northern Ireland Humanists in Northern Ireland in 2018. Humanist celebrants were accredited to give legal marriages in Jersey that same year, followed by Guernsey in 2021. Humanists UK continues to work for the same recognition of its ceremonies in England, Wales, and the Isle of Man.

It lies within our power, if we so desire it, to make the familiar world we inhabit more worthy of […]

The death of Shaw is to progressive people of the twentieth century what the death of Voltaire must have been […]

Her beautiful life, her truth, her unwearied charities, proceeded from her own heart. They were not inspired by any thought […]

Emilie Holyoake-Marsh, daughter of George Jacob Holyoake, was an activist for worker’s rights and women’s suffrage; an advocate of co-operation, […]