What primarily unites Humanists is not a set of propositions to be believed but moral values to be freely chosen… Humanists may belong to different philosophical schools, but they are more concerned with changing the world than describing it.

The Humanist Alternative was a pamphlet published in 1963 by the newly formed British Humanist Association—a partnership between the Ethical Union and the Rationalist Press Association. Four years later, the Ethical Union would formally become the British Humanist Association (and later still Humanists UK), but the 1963 venture represented a partnership between two humanist bodies, inaugurating a new era of organised humanism.

President PROF A. J. AYER, FBA

Vice-President THE BARONESS WOOTTON

Director H. J. BLACKHAM

Group Organizer M. L. BURNET

Information Officer T. B. VERNON

13 PRINCE OF WALES TERRACE, LONDON, W8 (WESTERN 2341)

Secretary Mrs G. C. DOWMAN

Editor of Publications HECTOR HAWTON

10 DRURY LANE, LONDON, WC2 (COVENT GARDEN 2077-8)

Advisory Council

| Leo Abse, MP | Prof A. Haddow, FRS |

| Austen Albu, MP | Dr James Hemming |

| A. L. Bacharach | Dr Peter Henderson |

| Sir Gerald Barry | Lord Holford, ARA, FRIBA |

| H. L. Beales | Sir Julian Huxley, FRS |

| Prof J. D. Bernal, FRS | Margaret Knight |

| Dr Cyril Bibby | The Earl of Listowel, PC, GCMG |

| Prof H. Bondi, FRS | Prof Hyman Levy |

| Dr J. Bronowski | Joan Littlewood |

| Brigid Brophy | Prof H. C. Longuet-Higgins, FRS |

| Prof Ritchie Calder, CBE | R. L. Marris |

| Prof G. M. Carstairs | Kingsley Martin |

| Lord Chorley, QC | Yehudi Menuhin |

| Prof F. A. E. Crew, FRS | A. S. Neill |

| Francis Crick, FRS | Kathleen Nott |

| R. H. S. Crossman, MP | A. Oram, MP |

| Prof C. D. Darlington, FRS | Lord Boyd Orr, FRS |

| H. L. Elvin | Vanessa Redgrave |

| Prof H. J. Eysenck | Earl Russell, OM, FRS |

| Prof Raymond Firth, FBA | Prof P. H. Nowell-Smith |

| Allan Flanders | Dr J. M. Tanner |

| Sir Gilbert Flemming, ксв | Peter Ustinov |

| Prof A. G. N. Flew | Prof C. H. Waddington, FRS |

| Prof P. Sargant Florence, CBE | Lord Francis-Williams, CBE |

| E. M. Forster, CH | Lord Willis |

| John Freeman | Prof J. Z. Young, FRS |

| J. S. L. Gilmour | |

| Prof Morris Ginsberg, FBA |

To develop a movement which will spread Humanist ideas and organize its members for fellowship and common action in Great Britain.

In pursuance of this object the BHA will provide for the publication of books, pamphlets, and periodicals, arrange conferences and courses, promote campaigns, and form local Humanist groups.

That man has only his own intellectual, moral, and social resources with which to face his prob-lems, and cannot rely on any absolute authority or power.

That human life can be made worth while and sufficient in itself, and that scientific knowledge and social organization should be used to provide the greatest possibilities for all human beings to develop their potentialities.

That freedom of thought and civil liberties as defined by the UN Declaration of Human Rights ought to be upheld in any society in which they have been established, and ought to be worked for in any society in which they have yet to be established.

Many people today are Humanists without knowing it. They do not know it because until now there has not been any organization in the United Kingdom calling itself ‘Humanist’.

Many people today are Humanists without knowing it. They do not know it because until now there has not been any organization in the United Kingdom calling itself ‘Humanist’. It is to meet this situation that the Rationalist Press Association and the Ethical Union have jointly brought into being the BRITISH HUMANIST ASSOCIATION. Both these bodies have the same basic aims and their separate existence is largely an accident of history.

The Ethical Union was founded in 1896 when there were already many Ethical Societies, most of them working with Fabian and other progressive groups. The Rationalist Press Association was formed three years later in the rooms of the Ethical Union, Surrey House. Both these organizations have worked in close harmony, but the RPA, as its name suggests, concentrated mainly on publishing.

Together they fulfilled the functions of a Humanist movement before it was generally recognized under this label indeed, before there was such widespread interest in its ideas as has now been awakened, not only in this country but throughout the world.

The fact that twenty-two nations were represented at the third Congress of the International Humanist and Ethical Union held in 1962 shows that Humanism is established as an international movement. It was an anomaly that British delegates to the Congress did not represent a society known as ‘Humanist’ because none existed. Nothing but confusion could result from a continuance of this ambiguity. Accordingly the Ethical Union and the RPA decided to form a united front. While retaining for practical reasons their independent status, the two organizations will use their respective facilities to promote the BRITISH HUMANIST ASSOCIATION.

(Broadly speaking the RPA will be concerned with publishing and the EU with public relations.)

The machinery of the Ethical Union will be used to form new Humanist groups throughout the country, where like-minded men and women can make social contacts, clarify their ideas, and participate where possible in local affairs.

This means that all who join the BHA will be also entitled to apply for full membership of both the sponsoring bodies. All members of the BHA will receive without further payment copies of The Humanist (monthly journal of the RPA), the Rationalist Annual, and Humanist News (10 times a year). From time to time the RPA will publish books of special relevance to Humanists, some of which will be available in cheap members’ editions.

The machinery of the Ethical Union will be used to form new Humanist groups throughout the country, where like-minded men and women can make social contacts, clarify their ideas, and participate where possible in local affairs. Regular conferences, courses, public meetings, and study groups will also be organized. In this way the Humanist movement will be enabled to make an impact on public opinion. With the long experience in these activities of the sponsors at its disposal the BHA will start fully fledged.

The time is ripe for this venture. The steep decline in Church membership reveals the hollowness of the claim that Britain is a Christian country… The truth is concealed by public lip-service to religion and the introduction of compulsory worship in schools.

The time is ripe for this venture. The steep decline in Church membership reveals the hollowness of the claim that Britain is a Christian country. As Prof G. M. Carstairs said in his 1962 Reith Lectures: ‘In our society there are still some people who sincerely believe in the teachings of the Christian Church, but the Church’s own statistics show that they have become a minority group a—rather small minority.’

The truth is concealed by public lip-service to religion and the introduction of compulsory worship in schools. Some Christians realize as clearly as Humanists that the inevitable hypocrisy of such a public policy too often leads to cynicism and indifference. They would welcome greater honesty, whether it led people back to the Church or away from it.

The early rationalists and freethinkers were concerned to take people out of the Church. In these days of empty pews we have entered a new phase. The main appeal of modern Humanism is to those who do not in any case look to the Church for guidance and have so far been unable to find a satisfying alternative. The dogmatic framework of Christianity has been so shaken that sincere believers fall mainly into two classes: the very clever, who invent new and sophisticated reasons, and the very simple who do not require reasons. And by insisting that morality is impossible without a religious basis the Churches are partly responsible for the moral vacuum of which they complain.

What primarily unites Humanists is not a set of propositions to be believed but moral values to be freely chosen. Humanism is a new way of life rather than a system of philosophy. Humanists may belong to different philosophical schools, but they are more concerned with changing the world than describing it.

Humanism is able to fill this void. Its immediate appeal is to all thinking men and women who seek reasonable guidance in the living of their lives but who cannot accept the traditional authorities. What primarily unites Humanists is not a set of propositions to be believed but moral values to be freely chosen. Humanism is a new way of life rather than a system of philosophy. Humanists may belong to different philosophical schools, but they are more concerned with changing the world than describing it.

Morals, as much as tools, are man-made. Man is an ethical animal. He has developed qualities of altruism and rational foresight which distinguish him from other animals and have been largely responsible for his survival.

This does not mean that they lack beliefs. They regard the corpus of science as the most reliable account we possess of the nature of man and his place in the universe. It is not accepted as final truth, but as an ever closer approximation as knowledge advances. On this view man is the product of an evolutionary process over which he can now exercise considerable control. The moral values we choose determine the direction in which civilization will evolve.

Our values themselves have evolved. Morals, as much as tools, are man-made. Man is an ethical animal. He has developed qualities of altruism and rational foresight which distinguish him from other animals and have been largely responsible for his survival. Unless they are used the power of destruction that science has now placed in our hands puts future survival in question.

In Schweitzer’s phrase, Humanism is ‘Life-affirming’, not ‘Life-denying’. Life is worth while because of the possibility of happiness. Thus a Humanist morality is directed to the removal of frustration—especially such obstacles to fulfilment as poverty, disease, and ignorance. Humanists believe that scientific techniques will solve most of these problems if they are diverted from instruments of death to the service of life.

The meaning of each individual’s life is the purpose which he gives it—the values to which he commits himself. The Humanist commitment is expressed by Bertrand Russell: ‘The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.’

For the individual life is bounded by birth and death. We know nothing of any cosmic meaning to our existence. The meaning of each individual’s life is the purpose which he gives it—the values to which he commits himself. The Humanist commitment is expressed by Bertrand Russell: ‘The good life is one inspired by love and guided by knowledge.’

Personal and social morality are interdependent. The Good Life implies an aim beyond immediate satisfactions—an effort to build the Good Society. The ultimate goal of Humanism is a new type of civilization in which the expanding resources of science will be used for the welfare and happiness of mankind. Partial interests must be subordinated to the whole if the conquest of Nature does not lead to catastrophe.

The Good Life implies an aim beyond immediate satisfactions—an effort to build the Good Society. The ultimate goal of Humanism is a new type of civilization in which the expanding resources of science will be used for the welfare and happiness of mankind.

The emergence of modern Humanism is the natural outcome of the advance of science. It can be viewed as the consciousness of the fact that we are no longer at the mercy of blind forces. By understanding them we can control them; and by understanding himself man can make himself. Humanism enables us to understand the forces within ourselves and to master them, as well as those of the physical world. At this critical stage of history the risks are too grave to rely for moral leadership on outmoded faiths with crumbling foundations.

‘To replace the conception of man as the subject of a heavenly King, which dominates the whole ancestral order of life, Humanism takes as its dominant pattern the progress of the individual from helpless infancy to self-governing maturity. Everyone today is compelled to choose consciously and clearly between religion as a system of cosmic government and religion as insight into a cleansed and matured personality.’ (Walter Lippmann.)

Humanism is older than Christianity.

Humanism is older than Christianity. Whereas the Christian tradition had its origins in Israel, the origins of western Humanism are to be found in Greece. A revolution in human thinking occurred in Ionia in the sixth century BC. A group of profoundly original thinkers asked searching questions about the origin and nature of the universe. What was so novel was that instead of accepting the answers handed down by priestly authority they tried to work out explanations by the use of reason. Civilized communities had been in existence for thousands of years and great empires had risen and declined, but there is no trace of any such intellectual curiosity before. The theories these remarkable men devised have only a historical interest today; the important discovery they made was theorizing.

This was the beginning of the scientific adventure, a breakthrough from the infantile fantasies of mythology to reality-thinking. A stream of ideas began to flow in independence of religious tradition. As history shows, it was frequently driven underground. There were periods of active persecution. There were attempts to harmonize the two traditions.

In the process thought was progressively secularized. The supernatural agencies which had been believed to control the forces of Nature were reduced in number until only one was left—the concept of an omnipotent ruler. As early as the fifth century there were even doubts of the existence of any supernatural powers. To the philosopher God became a highly abstract concept, the Unmoved Mover of a universe he did not create because it had always existed. The centre of interest shifted to man. ‘Man is the measure of all things’, said Protagoras.

The Greeks were concerned with problems of secular morality and blueprints for an ideal society. They had none of the otherworldliness of those religions which focused attention on the salvation of souls.

Epicurus held that although the gods might exist they did not interfere. Fear of the gods, like the fear of death, must be banished from the mind.

Epicureanism spread and disturbed the authorities, who took the cynical view that superstition was useful to keep the masses quiet. Only a few fragments of what Epicurus wrote survive, but his system was superbly re-stated in the great poem of Lucretius.

Obviously, none of these ancient thinkers could have been a Humanist in the modern sense. Humanism was in the making. The secular process was unfolding. Different thinkers perceived different implications. The Greeks were concerned with problems of secular morality and blueprints for an ideal society. They had none of the otherworldliness of those religions which focused attention on the salvation of souls. The famous Oration of Pericles is one of the clearest expressions of classical Humanism.

Science never took root in India, where even philosophy was preoccupied with individual salvation rather than the pursuit of objective truth. In China science developed up to a point and the germs of Humanism can be found in the teaching of Confucius.

For three thousand years the great concern was with human relations. According to Prof H. G. Creel: ‘Confucius was not only willing that men should think for themselves; he insisted upon it… He believed that humanity could find happiness only as a cooperative community of free men.’

The lineaments of Humanism could be discerned under the thin coating of formal orthodoxy in the writings of Montaigne, Cervantes, and Erasmus. The more daring speculations of Bruno sent him to the stake.

Nothing could be more removed from the rigid uniformity imposed on Europe when Christianity became the official religion. Humanism reappeared at the Renaissance. In art there was a return to the Greek delight in the beauty of the human form and in philosophy to the Greek ideal of balance and harmony—’the complete man’. More far-reaching consequences came from the scientific revolution started by Galileo. The lineaments of Humanism could be discerned under the thin coating of formal orthodoxy in the writings of Montaigne, Cervantes, and Erasmus. The more daring speculations of Bruno sent him to the stake.

Open scepticism remained dangerous. Thomas Hobbes had to be circumspect, and even in the eighteenth century David Hume veiled his criticism of religion in bland irony. The path to agnosticism and atheism followed a roundabout route via Deism and Unitarianism. Thomas Paine in England and Voltaire in France rejected dogmatic Christianity but retained belief in ‘the God of the Philosophers’. But their passion for social justice and affirmation of the rights of man and the principle of toleration was Humanism in action.

Thomas Paine in England and Voltaire in France rejected dogmatic Christianity but retained belief in ‘the God of the Philosophers’. But their passion for social justice and affirmation of the rights of man and the principle of toleration was Humanism in action.

Tributaries of the older Humanism merged into a broad stream during the period known as the Enlightenment. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries concepts of human equality and political democracy appeared. Part of the blame for the French Revolution was laid by Macaulay and Bruntière on what they thought were misunderstandings of Chinese institutions. Some of the French philosophes—e.g. Condorcet, D’Holbach—were frankly atheists and materialists.

Tributaries of the older Humanism merged into a broad stream during the period known as the Enlightenment… Some of the French philosophes—e.g. Condorcet, D’Holbach—were frankly atheists and materialists.

Of more practical significance was their conviction that human nature was indefinitely improvable—not perfectible, as is sometimes alleged—and that the aim of government should be the happiness of the people, as indeed Confucius had taught. These democratic notions were embodied in the American Declaration of Independence. In England, under pressure of the Industrial Revolution, they gave rise to the long series of reforms which made the nineteenth century a laboratory of social change.

Jeremy Bentham‘s Utilitarianism gave this resurgent Humanism a concrete programme based on the axiom that actions, laws, and institutions must be judged by consequences and that the final test was whether they increased the general happiness. The right method was to use political machinery and to plan social reform after careful study of evidence. Bentham was the father of Royal Commissions and the begetter of the Welfare State.

Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism gave this resurgent Humanism a concrete programme based on the axiom that actions, laws, and institutions must be judged by consequences and that the final test was whether they increased the general happiness.

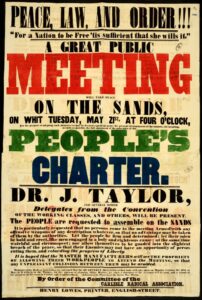

John Stuart Mill and the English radicals still further developed the democratic principle which is fundamental to Humanism. Mill was also a pioneer of the emancipation of women and birth control. The ferment of Humanist ideas compelled a critical examination of all laws deriving their sanctions from moral theology. Hence the institution of a Divorce Court, the triumphant battle for birth control by Annie Besant and Charles Bradlaugh, and the less successful fight against the Blasphemy Laws.

The latter part of the nineteenth century saw what has been called ‘the landslide of Victorian Unbelief’. The advance of science and Biblical criticism destroyed what was left of the traditional framework of religious orthodoxy. Darwinism brought man into the scientific picture. If Natural Selection was how evolution worked, there was no room for design in Nature. T.H. Huxley coined the word ‘agnosticism’ to describe what was also known as ‘rationalism’ or ‘Scientific Humanism’: namely, the attitude that it is wrong to believe anything for which there is no good evidence.

The latter part of the nineteenth century saw what has been called ‘the landslide of Victorian Unbelief’… T.H. Huxley coined the word ‘agnosticism’ to describe what was also known as ‘rationalism’ or ‘Scientific Humanism’: namely, the attitude that it is wrong to believe anything for which there is no good evidence.

These controversies went beyond mere intellectual debate. They were reflected in literature. The distress at the threat to religious faith was expressed in the poetry of Tennyson and Clough. The loss was flamboyantly accepted by Swinburne, urbanely by Edward Fitzgerald, stoically by A. E. Housman. The spirit of a new Humanism animated the novels of George Eliot, Thomas Hardy and George Meredith, and later the plays of George Bernard Shaw.

In the eighties a number of ethical societies (federated in the Ethical Union) responded to needs which the Churches could no longer meet. The National Secular Society carried its message to the man-in-the-street. At the turn of the century the Rationalist Press Association prepared a campaign through cheap books which did much to mould the minds of a new, largely self-educated public. The importance of concerting these efforts in a unified movement was obvious once it was clear that moral leadership was passing from the Churches.

The British Humanist Association represents a new phase in the secular process… Now that religious dogmas seem to so many to be dissolving in the acids of modern criticism the task of Humanism has become constructive.

The British Humanist Association represents a new phase in the secular process which began with the origin of western science. Now that religious dogmas seem to so many to be dissolving in the acids of modern criticism the task of Humanism has become constructive. The secularization of thought is a prelude to the secularization of life and society. In the words of Sir Julian Huxley:

‘There have been two critical points in the past of evolution, points at which the process transcended itself by passing from an old state to a fresh one with quite new properties. The first was marked by the passage from the inorganic phase to the biological, the second from the biological to the psychosocial. Now we are on the threshold of a third. As bubbles in a cauldron on the boil mark the onset of a critical passage of water from the liquid to the gaseous state, so the ebullition of Humanist ideas in the cauldron of present-day thought marks the onset of the passage from the psychosocial to the consciously purposive phase of evolution.’

Printed in Great Britain by Richard Clay (The Chaucer Press), Ltd., Bungay, Suffolk

The British Humanist Association is affiliated to the following organizations:

The National Peace Council

The Howard League for Penal Reform

The Council for Educational Advance

THE HUMANIST FRAME

Edited by SIR JULIAN HUXLEY

37s 6d (postage 2s 3d)

Published by Allen & Unwin

HUMANIST ANTHOLOGY

From Confucius to Bertrand Russell

Compiled by MARGARET KNIGHT

21s; RPA members’ edition, 10s 6d (postage 10d)

WHAT HUMANISM IS ABOUT

By KIT MOUAT

16s; RPA members’ edition, 10s 6d (postage 9d)

THE SCIENCE OF BEHAVIOUR

By JOHN McLEISH

18s 6d (postage 10d)

The Humanist Library

THE HUMANIST REVOLUTION

By HECTOR HAWTON

PIONEERS OF SOCIAL CHANGE

By E. ROYSTON PIKE

THE LOOM OF LIFE

A Simple Introduction to Modern Genetics

By RONA HURST

Each cloth, 15s (postage 8d); paper cover, 10s 6d (postage 6d)

BARRIE & ROCKLIFF

IN ASSOCIATION WITH

THE PEMBERTON PUBLISHING CO LTD

40 Drury Lane, London, WC2

Download The Humanist Alternative

No law can be effective which has not behind it the sanction of the people. Dorothy Thurtle, quoted by David […]

Why are these minds left without the means of obtaining that knowledge which they so ardently desire and why are […]

A mass working class movement for universal male suffrage Read more Chartist Ancestors and Women Chartists Chartism by David Avery […]

And how can woman be expected to co-operate unless she knows why she ought to be virtuous? Unless freedom strengthens […]